War was always here. Before man was, war waited for him. The ultimate trade awaiting its ultimate practitioner. That is the way it was and will be.— Judge Holden

Big Bang

Between 40,000 and 45,000 years ago, something happened which kickstarted the development of our species. This was the dawn of human culture, the “big bang of human consciousness”.

During the so-called Upper Paleolithic Revolution, humans began to create specialised tools, displaying for the first time a conceptual understanding of how to manipulate the environment. Bone needles for sewing, fish hooks, and even musical instruments like flutes made from bird bones emerged, reflecting a desire in our great ancestors for a life that would be about more than survival.

Humans also started to paint on their cave walls, these paintings usually took the form of storytelling. Typically, depictions of animals and our relation to them, though sometimes they experimented with abstract signs and geometric symbols.

Consider what a baffling development the appearance of the enormously complex brain of homo sapiens is. It has allowed us to conquer the entire planet and populate it with complex civilisation, and with it, art, philosophy, poetry, music. It has allowed us to develop weapons capable of wiping out our own species’ life on earth, to explore outer space, and eventually, perhaps, to leave the confines of earth and settle other planets.

Our enormously energy consuming brains are complex enough to produce the works of Shakespeare and discover the structure of sub-atomic particles, but this surplus of cognitive skills seems unnecessary for survival; after all, the other tens of millions of species get by just fine with just enough cognition to survive and reproduce.

How are we to make sense of this enormous great leap forward? Most have assumed a chance genetic mutation or series of mutations around this time which somehow set us on a course apart from any other hominids. This mystery has also prompted a number of more creative theories of what the “secret sauce” was that made us so unique.

Stoned Ape Theory, proposed by psychonaut philosopher Terence McKenna, suggested the ingestion of psilocybin mushrooms enhanced cognitive function and allowed early humans to trip out on abstract thought for the first time. Aquatic Ape Theory argues the key lies in our ancestors proximity to watery environments, where our fish-rich diet provided us with lots of fatty acids useful to brain development. Some have argued that sexual selection was key; for some reason, our species began to favour things like creativity and problem-solving in choosing a mate. But why? In the context of 45,000 BC, what are these traits really useful for?

One thing our big brains are very useful for is combat, and in the natural world, that means the capability of fending off any competitors for space and resources. The Australian anthropoligist Raymond Dart first proposed “The predatory transition from ape to man” in 1953. His theories were popularised with the bestselling African Genesis, written in 1963 by the American playwright Robert Ardrey, who became a vocal proponent of Dart’s Killer Ape Theory.

Ardrey’s work not only inspired many future scientists, but also reached a popular audience and captured the public imagination. One fan was Stanley Kubrick, who defended the violence of A Clockwork Orange by drawing on the work of Ardrey. In 2001: A Space Odyssey, the inspiration was evident, as Kubrick showed violence to be the cause of a breakthrough of consciousness in the famous “Dawn of Man” scene.

A number of scholars have continued to argue for warfare as the driving force in human evolution. An implication of these theories is that our brains are uniquely geared towards violence, warfare, and a natural hostility to outgroups, something which probably hasn’t helped its popularity against nicer sounding explanations which put our sociality and cooperation at the centre in our origin story.

Danny Vendramini, the author of Them And Us, is among those that still argue martial selection holds the key to understanding the mechanism that placed man above ape. But he is unique in placing our close relatives, the Neanderthals, at the center or this development.

Vendramini calls this mystery catalyst Factor X, and traces it to some set of conditions that existed in the Levant. Something which, after encountering, humans there emerged a totally new type of hominid to what had come before, adopting not just advanced cognition, but a number of unique physical features like hairlessness, enlarged sexual organs and breasts, smooth skin and clear eyes.

What were Neanderthals?

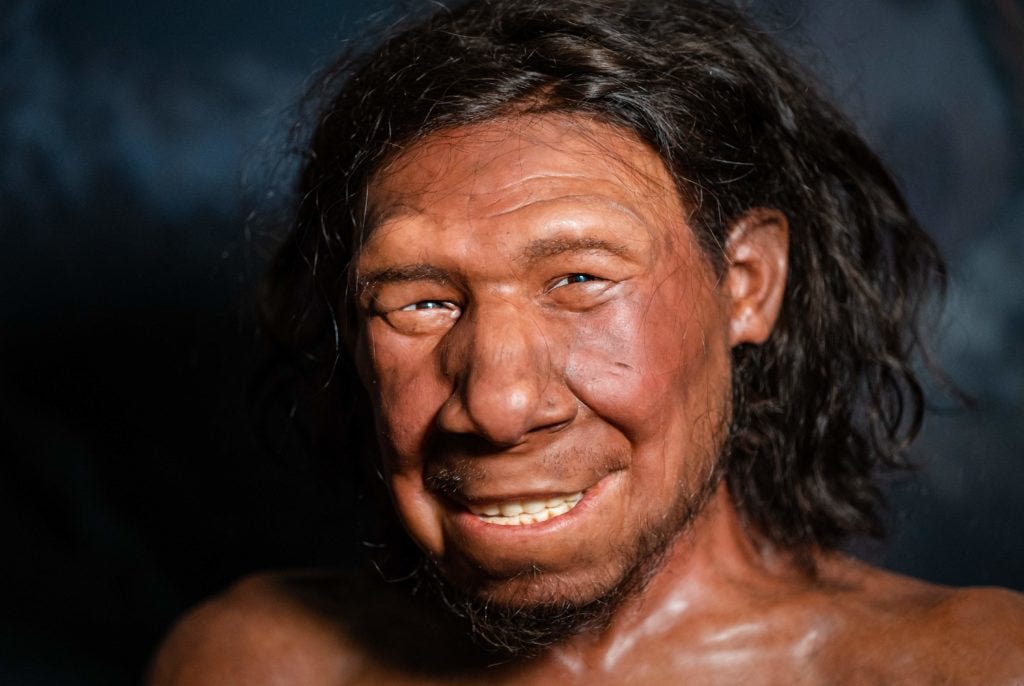

I recently watched a Netflix documentary titled Secrets of the Neanderthals. The message of the documentary was that Neanderthals were more complex, creative and compassionate than we have given them credit for. Neanderthals were portrayed as looking much like us, with no body hair and clear eyes, wearing primitive clothing and communicating in something like their own language.

This is the standard portrayal today, Neanderthals are made to look like primitive humans, who, we are told, may well have developed their own culture and high civilisation had they been free from human predation and interbreeding.

But there’s no reason to think Neanderthals had these uniquely human physical features. All 192 primate species other than humans have thick fur across their whole body. Neanderthals evolved in Ice Age Europe, and we assume every other mammal from this time had thick fur to be adapted to the cold climate. Vendramini puts aside our strange bias to anthropomorphise the Neanderthal and presents a picture of how these creatures would most likely have appeared.

Neanderthals weighed 25% more than us, and had thicker bones to support a far more bulky, muscular frame: “As for its body, it is so heavily muscled, it makes a human body builder look weedy by comparison.” They also had extremely thick skulls, useful for close-quarter combat. They had murch larger jaws and teeth, which would have exerted enormous, bone-crushing bite force. Analysis of Neanderthal spines suggest they were hunchbacks.

They used these predators’ teeth to consume enormous amounts of flesh — about four pounds of fresh meat per day. Bones of their prey litter Neanderthal cave dwellings, everything from gigantic woolly mammoths to cave bears and lions. These animals were deadly hunters themselves, but they were no match for the apex predator Neanderthal, who hunted with stone-tipped wooden spears.

The wild animals that roamed the glacial tundras of ice-age Europe not only fed and fuelled Neanderthals, they moulded them. Their ferocity, their will to live, their own acquired lethality raised the bar and forced Neanderthals to become tougher, smarter and more aggressive.

Another detail that has emerged about Neanderthals is that they engaged in cannibalism. Examination of Neanderthal sites has shown stone tools were used to break open the bones of their own to extract nutritious marrow. An excavation of a cave-site in the modern Netherlands showed that Neanderthals 100,000 years ago left a scene of butchery where:

Marks on the bones clearly reveal that these early humans filleted the chewing muscles from the heads of two young Neanderthals, sliced out the tongue of at least one, and smashed the leg bone of a large adult to get at the marrow. The bone fragments were apparently then dumped amid the remains of deer and other butchered mammals.

In El Sidrón in modern Spain, a Neanderthal cave revealed the bones of eight Neanderthals who had been victims of cannibalism, including two teenagers, a child and a baby. Perhaps suffering a shortage of meat, or perhaps as part of some primitive quasi-religious ritual, the Neanderthals used hand axes, saw-toothed knives and scrapers to deflesh their young victims.

Vendramini postulates that Neanderthals were nocturnal hunters, with their large eye sockets suggesting eyes made for night-time hunting, and their broad noses well adapted to hunting by scent.

Adapted to Ice-Age Europe over hundreds of thousands of years, Neanderthals were shaped by the cold, predator-rich environment to become super-predators, with successive generations of adaptations breeding a tough, aggressive and cunning killing machine:

The Neanderthal that Vendramini describes is thus a terrifying creature: A hunched cannibalistic predator with large, shining eyes and an animalistic snout, covered by thick fur and massive muscles, built for close combat, hunting by night, with a brutish and guttural voice, and a huge mouth with huge teeth and powerful jaws. It didn’t look like Fred Flintstone.

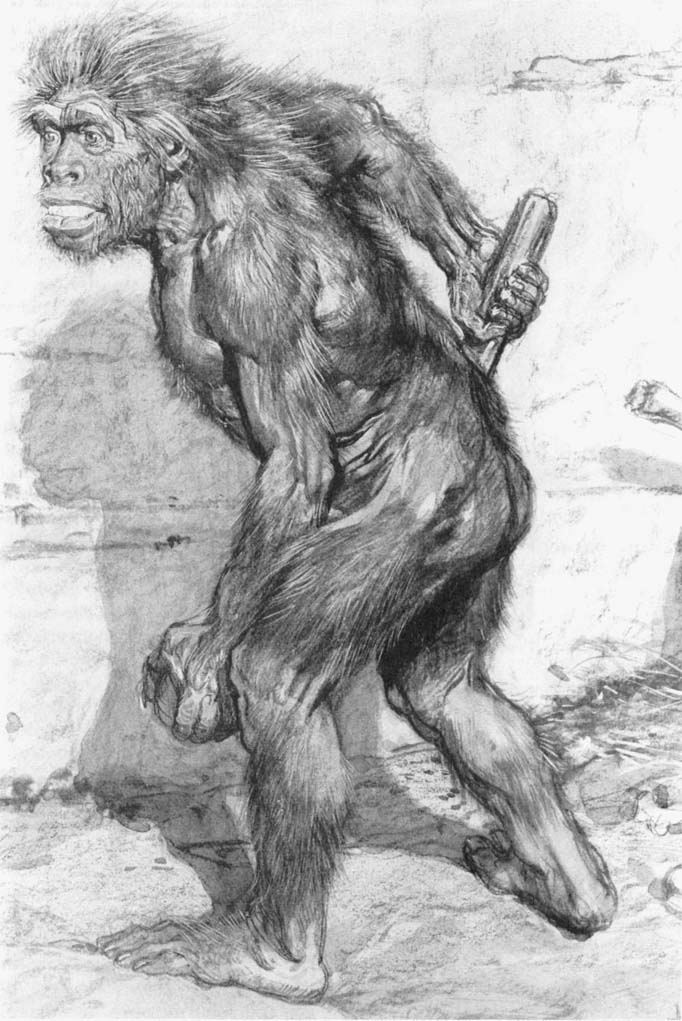

Vendramini presents the following illustrations of his proposed Neanderthal:

Perhaps a little sensational. But maybe early illustrations of Neanderthals, like this one made in 1908 by Frantisek Kupka, were closer to reality than what has come with the modern craze to portray Neanderthals as similarly to us as possible:

Neanderthals meet humans

Lethal raiding is a common behaviour observed in carnivorous group animals. It involves “the intrusion by a group of predators into a neighbouring territory, specifically to conduct a surprise attack, cause casualties, and retreat to the home territory”.

It was once thought primates did not engage in this behaviour, until the 1970s, when Jane Goodall documented it in the Gombe Stream National Park in Tanzania, observing male chimpanzees organising warbands to raid each other’s territory. The warring chimps would leave the mutilated bodies of their enemy tribe strewn on the battlefield, and even cannibalise their competitors.

In numerous long-term studies since, prolonged “gang-violence” among chimps has been well documented:

In one case that is hard not to see as a war, the adult males of one community systematically attacked and killed the males of another group over a period of years, with the victorious group eventually absorbing the remaining victims.

In 2021, researchers documented, for the first time, a lethal attack raid by chimpanzees on gorillas in Loango National Park in Gabon:

In the encounters, which lasted 52 and 79 minutes, the chimpanzees formed coalitions and attacked the gorillas. The two silverbacks of the two groups and the adult females defended themselves and their offspring. Both silverbacks and several adult females escaped, but two gorilla infants were separated from their mothers and were killed.

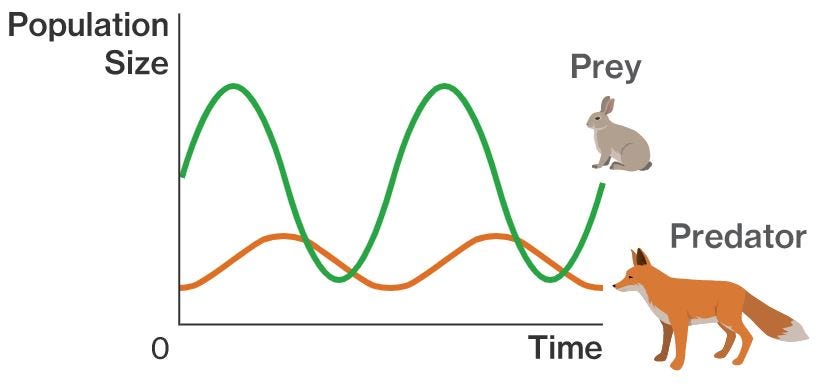

Since this seems to be a ubiquitous behaviour in prehistoric hominids, it was almost certainly a part of Neanderthal behaviour. While they lived in isolation in Europe, they could only have directed this against each other. But when European Neanderthals migrated to the Levant between 50,000 and 70,000 years ago (to become the Eurasian Neanderthal), they would have suddenly encountered Skhul-Qafzeh humans:

a less aggressive, more docile, but nevertheless sexually compatible option— not to mention an alternative supply of fresh meat during times of food stress. They represented a ‘soft’ target for aggressive Eurasian Neanderthals. This—and the margin of safety it provided—would have encouraged lethal raiding against Levantine early humans.

We can scarcely imagine the horror our distant ancestors must have experienced when these far more powerful and deadly creatures emerged from the dark of night, wielding their stone tipped weapons, to slaughter their males and kidnap their women, dragging them back into the dark abyss never to be seen again.

Skhul-Qafzeh humans likely put up little fight against their more deadly competitors. They had an omnivorous diet and hunted little large-prey, instead supplementing their diets with meat from small game. They lacked the deadly hunting-adaptations of true carnivores, but were now encountering a carnivorous primate with millennia of natural selection battling the most deadly predators in Ice-Age Europe. Never true predators, they were now in the terrifying position of being the prey for a new, invasive species.

Them and us

According to Vendramini’s theory, the threat of Neanderthal predation would have been massively transformative to the behaviour and mindset of our early human ancestors.

Recent research has argued Neanderthals and Skhul-Qafzeh humans were sexually compatible and could produce fertile offspring. A 2016 paper in Nature discussed the emerging evidence for an “interbreeding bonanza” between Neanderthals and ancient humans. DNA analysis on the jawbone of a 40,000 year-old human skeleton found in Romania suggested the individual had a Neanderthal great-great grandparent.

Since Neanderthals would have had a huge physical advantage over their new prey population, they may have pushed them to the brink of extinction — something Vendramini argues is supported by the genetic record. This event, and the response of our early ancestors to it, would have forced them to adapt their behaviour, and their own physical constitution through new mating strategies, to survive against this grave threat.

If we are looking to explain a Factor X which sparked a remarkably rapid and anomylous evolution in unique traits in modern humans, a great population bottleneck caused by the introduction of a new predator is a good candidate.

A near-extinction event would have narrowed down the conditions for survival so much, that what was adaptive enough to survive the event could have been different from what came before in a way that would otherwise require a huge timespan of successive adaptations:

In effect, a near-extinction event was the door through which our ancestors had to pass. On one side, they were primitive stone-age people. But when they emerged on the other side, they were fully human, smart and articulate—much like us.

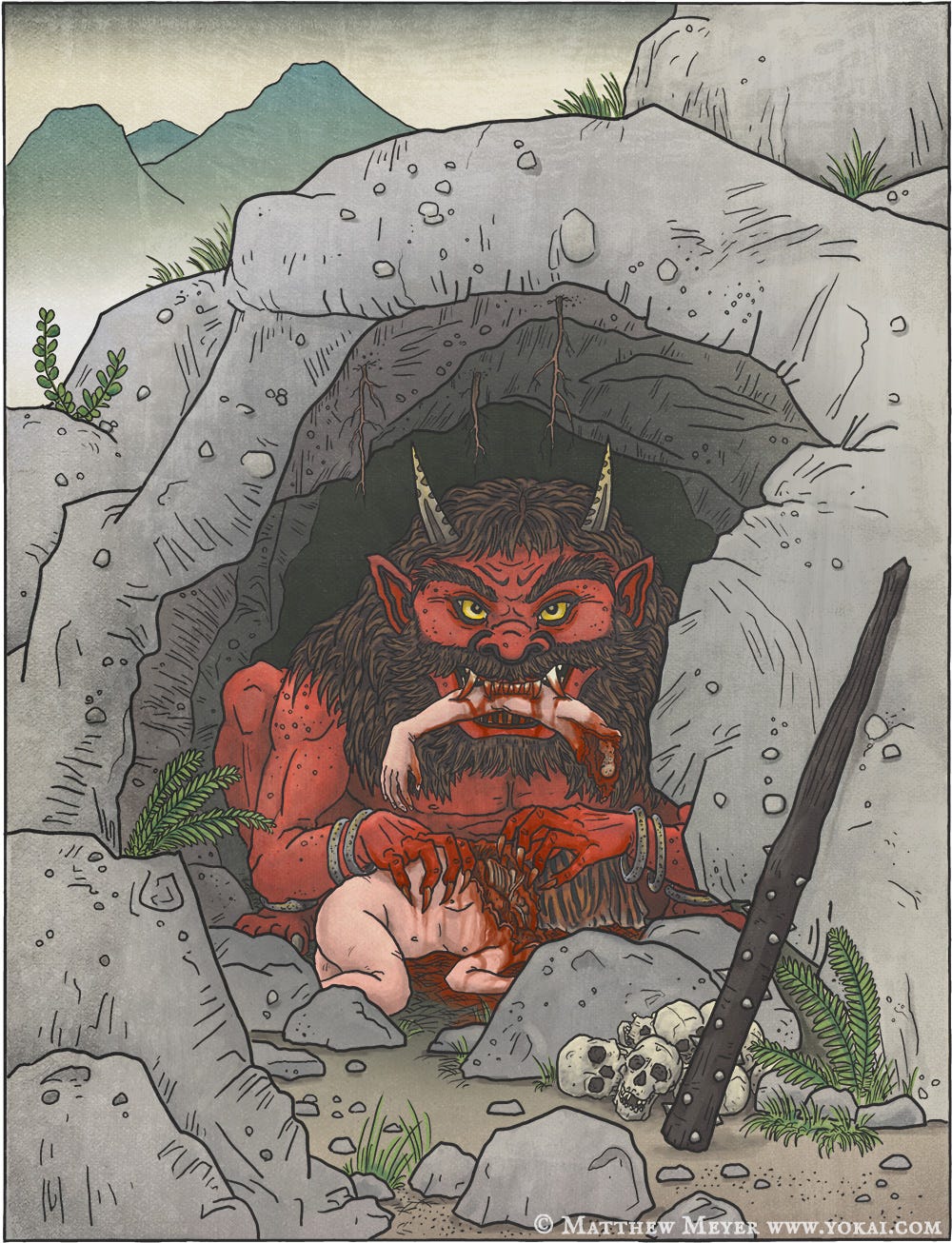

Humanity’s encounter with Neanderthals must have been an extraordinarily traumatic encounter. And we can imagine tales of these encounters and our unlikely triumph survived long after the neaderthal through stories passed on generation to generation. Over time, these would perhaps have taken on magical and mythological elements, and become immortalised in folk tales.

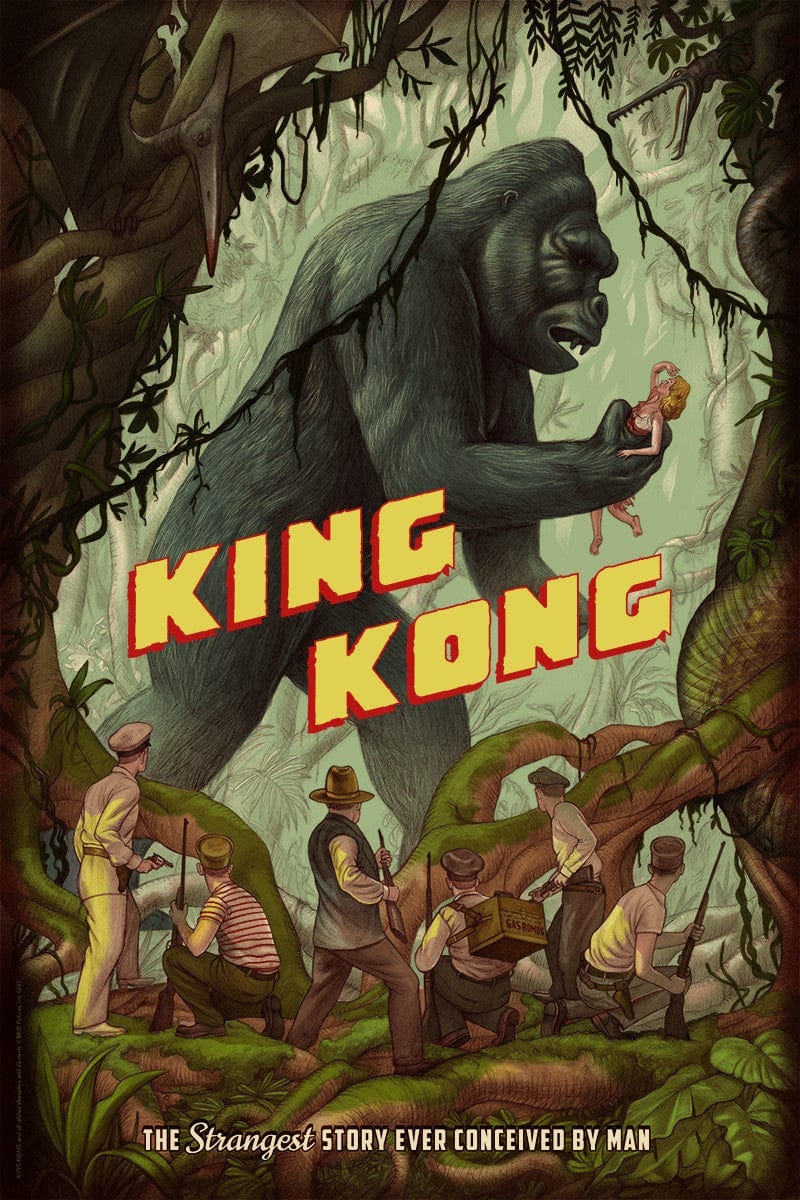

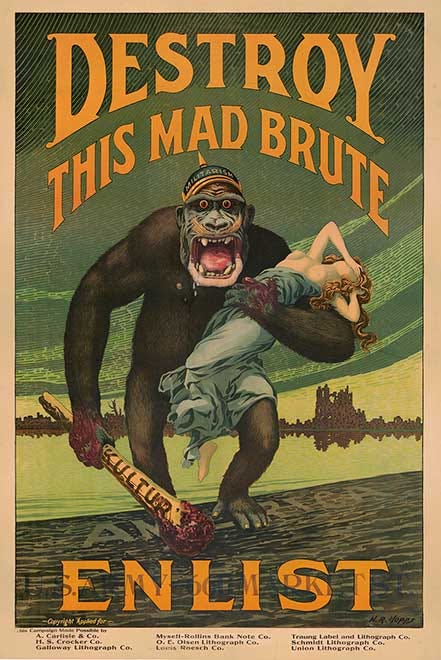

And indeed, when we look across cultures, we find an ever-present figure of the half-man half-beast: minotaurs, trolls, ghouls, ogres, yeti, oni, cyclops, etc. These beasts are often wild, hairy, forest or cave-dwellers, who terrorise the collective with their brute strength and steal away the young women to take back to their dark lair.

Could this universal archetype be the holdover of an old story etched into our collective memory: our encounter with other, more beast-like hominids, where the warrior capable of winning battle against them was celebrated by the collective as the greatest hero?

The fear of “brutes”, of subhuman ape like creatures is evidently still a powerful subconscious force among modern humans, repeated in cinema, and even war propaganda as a way to gin up fear and hatred of the enemy, and these portrayals typically include “the mad brute” stealing away an attractive young lady of the home nation.

War-making apes

Vendramini argues that the existential threat created by Neanderthal predation would have pushed early humans to favour “anti-Neanderthal” traits and social adaptations.

We would also have developed adaptations other prey species have, like being able to run fast — and indeed, we have far superior distance running skills to other primates. But at some point, we would have had to turn the tables on our predator, and go from hunted to hunter. Strategic adaptations in combat would have been so prized, and so concentrated in a population near extinction, that our prey species could very rapidly have developed into a great martial species.

Lacking the power and aggression of Neanderthals, these early humans would have been forced by necessity into coalescing into a militaristic society, here again, we observe that the traits which favour making good soldiers are precisely the traits that have allowed for complex societies and innovation: male aggression and dominance; self-sacrifice and courage to fight back, even at the cost of individual life; creativity, language and organisation to plan against the enemy’s strength advantage; gender roles and division of labour to specialise in certain areas and innovate against the enemy.

Also prized would have been the anomalous intelligence of the rare individual who could innovate new war-making tools against the Neanderthal. Innovations like slings, javelins and poison darts require the kind of imagination and abstract thought unique to our species, and so:

The creative proto-geniuses who invented the latest ‘high tech’ weapon would be respected, revered and much sought after as mates, which would propagate the genes for creativity. In other words, the proto- war with the Neanderthals generated tremendous selection pressure for the kind of lateral thinking and imagination that could produce strategic weapons.

Cognition, not brute strength, was now the instrument driving human survival and expansion. While our energy-consumptive brains might not be adaptive for the basic necessities of survival, they are most useful as a means of defeating a stronger predator species.

Beautiful people

One of the most dubious aspects of Vendramini’s theory is his novel view that trauma is somehow encoded in DNA, and it was an “anti-Neanderthal” push by the beleaguered early humans that caused us to value anti-Neanderthal traits we now associate with attractiveness. This trauma would then have been passed on as a kind of encoded collective memory to future generations. It’s a creative theory, but there is surely a simpler explanation for the kind of uniquely human features we tend to favour.

In an essay titled “Warlord Harem Hypothesis”, Matt Parrott proposes another variant of Killer Ape Theory. The crux of this theory is that sexual selection was the driver of human evolution, and it was most intense in the fertile regions where there was endemic warfare between primates. There, successful warriors would have enjoyed a polygynous mating dynamic where they had a good choice of females and would thus pass on more attractive traits to their children:

The males were subject to acute selection for greater intelligence while the females were subject to acute (but primarily assortative) selection for neoteny, gracility, and secondary sexual development. While taste surely varied then as it does now, a cross-cultural analysis confirms that there are a handful of objective, universal traits that tend to be selected for by men; youthful appearance, delicate appearance, and exaggerated signs of pubertal development.Perhaps counter-intuitively, but logically, endemic warfare selected the originally robust apes for the very childlike and feminine appearance that separates us from our nearest primate relatives. Every physical difference between humans and great apes can be explained by either this process or by our bipedal adaptation to wielding tools and weapons, with the human populations most acutely and recently subjected to precivilized endemic warfare exhibiting the greatest degrees of neoteny, gracility, and secondary sexual development.

So endemic warfare can set in motion two interrelated processes: suddenly rewarding an excess of cognition in males, and allowing those males to create a kind of aesthetic eugenic practice through a more picky selection of females.

To illustrate this dynamic with an example from the human world, it has been estimated that 16 million men descend directly from Genghis Khan. The warlord survived an intense selection process to unite the Mongol tribes and conquer the largest land empire ever, and had complete freedom in choosing who to reproduce with in his newly conquered lands.

His bravery and success as a military tactician allowed him not only to outbreed anyone else alive at the time, but to choose the most attractive females, meaning the successive generations held more of both the abtstract male intelligence needed to organise conquering most of the world, and more of the universally favoured signs of female attractiveness.

Genghis Khan might seem like a historical anomaly, but genetic evidence has shown us that a “winner take all” dynamic was the norm for males before civilisation: In 2015, scientists made the fascinating discovery that during the Stone Age, the standard was for one male to reproduce for every 17 females.

Martial selection has also happened between groups throughout history. When the warlike Proto-Indo-Europeans emerged out of the Steppe and conquered Northern Europe and parts of Asia, they wiped out the lineages of less combative indigenous groups:

In vast regions of Northern Europe, the Bronze Age steppe herders replaced earlier farming societies, the invaders unceremoniously sweeping away all before them, which often meant the extermination of indigenous male-dominated elites (ancient DNA studies show that Neolithic farmers too structured their societies around male kin-groups).

This leads us to some interesting considerations. If this pattern holds, you would expect more martially selected peoples to have higher intelligence, and possess more feminine, youthful features. Peoples who faced little comeptition for resources would be the opposite, and perhaps live more content with what is immediately supplied by nature.

If the model is true, and this selection process happened most where there was the most population density, we would expect to see victorious groups of these martially selected populations emerging from these areas. And indeed, most of the “cradles of civilisation” where complex human societies first emerged are fertile river valleys, perhaps once host to endemic primitive warfare. In contrast, regions without these sites of intense competition would have had little sexual selection or loss of genetic diversity to conquest. We find today that a place like Papua New Guinea alone — never subject to this intense resource competition — has enormous diversity, home to thousands of native tribes and hundreds of individual languages. It also seems to have, according to most IQ research, the lowest average IQ in all of Asia or South-East Asia.

So we don’t need Vendramini’s elaborate theory about human’s unique aesthetic features and martial prowess developing specifically as an “anti-Neanderthal” trend enforced by the collective. These traits could have been the result of anything that enduced endemic warfare against other hominids (not necessarily Neanderthals) or just between human tribes. This would explain a general pattern in the development of humans, with complex civilisations emerging out of migrations from fertile river valley regions that became the cradles of civilisation, since it was in these cauldrons of endemic warfare that martial evolution was most rapid.

Moreover, there is good reason to reject his belief that the battle to near extinction with Neanderthals included all of what would become modern humans, confined to the Levant. We have evidence that humanity was much more dispersed at this time.

We know, for example, that aboriginal people have occupied the Australian mainland for at least 65,000 years. Genetic testing has shown substantially more Neanderthal DNA in non-African populations, especially East Asians and Europeans. As the geneticist David Reich recently explained in an interview, for a non-African person, it is likely that between 10 and 20% of their ancestors are Neanderthal. Africans have some, but substantially less Neanderthal ancestry, coming from migrations of Eurasian modern humans to Africa after the Neanderthal’s extinction.

Another part of this story is the mysterious “Ghost DNA” of a now extinct species, which scientists estimate comprise as much as 19% of the DNA of some West African populations. It is estimated this is the result of interbreeding that occurred 43,000 years ago, around the same time Neanderthals were disappearing from the planet and and a new type of human was emerging in the Levant. So, while one set of future humans were mixing with Neanderthals in the Levant, another group were interbreeding with a different non-human species in West Africa.

Another recent discovery to come from genetic science is that South-East Asians hold DNA belonging to the now extinct Denisovans, a species of archaic human only discovered in 2010, who left Africa as far back as 800,000 BC. Analysis of DNA in Maritime Southeast Asia, a region encompassing the countries of Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and East Timor, found that “the levels of Denisovan DNA in contemporary populations indicate that significant interbreeding happened.”

The interbreeding with Denisovians is presumed to have happened 50,000-60,000 years ago in this region of Asia, including with humans who moved there on their way to Australia. Scientists now estimate that 3-5% of the DNA of aboriginal people of Papua New Guinea, Australia, the Philippines and other nearby islands came from Denisovans. This is more admixture than Eurasian people have with Neanderthals. These natives also carry DNA from a third, yet unidentified extinct human species.

Thinking about the interactions with other, non-human hominids and how this differed across regions, a story still told in today’s genetics, should make us consider the profound differences between human races. Discoveries like this have done little to shake the deeply held belief in blank-slatism, either in the social sciences or among the general public, but this reflects only how irrationally held that dogma is.

The Social Contract

Many social scientists remain baffled at our species’ eagerness to engage in war, our willingness to kill those so similar to us, and face near certain death and the extinction of our own reproductive potential, as something so obviously maladaptive to our survival. Frankfurt School psychologist Erich Fromm termed our capacity to kill without an immediate biological necessity “malignant aggression”, something he considered to be self-evidently maladaptive.

Robert Ardrey called this the romantic fallacy, the idea inherited from Enlightenment political philosophers like Rousseau that man is naturally good, and the injustices and evil we see in society are the result of culture, not nature. In the 20th Century, academics extended the romantic fallacy — beyond just blaming culture for inequality, violence and criminality, they began to argue that even the belief in racial differences and behavioural differences between the sexes are purely social constructs. E. O. Wilson would later call Ardrey “the father of evolutionary psychology” for applying findings on ape behaviour to challenge the environmentalist, Boasian orthodoxy in anthropology.

As Ardrey saw it, the social scientists had it backwards. Violent crime was not the result of some toxic corrupting influence of society, but a breaking through of our more primal nature against the constraining influences of society. War, or organised violence, is as natural to humankind as any institution. Nationalism and xenophobia are not ideas like any other, but the expression of our deepest territorial instincts:

Animal xenophobia is as widespread a trait among social species as any single trait we can study, and reasons for its incidence abound.…

The howling monkey roars, alerting his fellows in the clan; the spider monkey barks; the lion, without ceremony, attacks. However the animosity for strangers is expressed, whether through attack or avoidance, xenophobia is there, and it is as if throughout the animal world invisible curtains hang between the familiar and the strange.

While the study of our origins remains hotly contested and routinely upended by new information from a variety of fields, there is enough information at hand to discard the anti-European, anti-White anthropological myths of the 20th Century. We did not all recently arrive “Out of Africa”. The races of mankind are not nearly as related as we were told, with differing rates of admixture with ancestral subspecies that diverged from one another perhaps a million or more years ago.

Though much of this is necessarily in the realm of speculation, I believe that future genomic modeling and archaeological discoveries will vindicate Raymond Dart, Konrad Lorenz, Robert Ardrey, and other supporters of variants of the Martial Ape Theory. If this theory is true, then war is anything but a creation of advanced society — peace is the exception to the rule of endemic tribal, territorial aggression. War is fundamental to human nature because war created human nature.

Something clearly changed with the advent of sedentary civilised society, a change that sublimated human competition into managerial and memetic alternatives to martial conflict. But have the stakes changed all that much? Just because it’s now mostly performed with popular narratives and public notaries instead of bare knuckles and bloody knives matters little in the grand scheme of things. The future still belongs to those tribes who defend their territories.

Notes

https://treeofwoe.substack.com/p/when-orcs-were-real

Jones, Dan. “Human behaviour: killer instincts.” Nature 451, no. 7178 (2008).

Ardrey, Robert. “The Social Contract: A Personal Inquiry into the Evolutionary Origins of Order and Disorder.” (1970). Pg. 194 & 221.