Anthony Walsh, Sexuality and Crime: A Neo-Darwinian Perspective, Routledge, 2023, 123+x pages, $54.99 paperback

Criminology, like other social scientific disciplines, has long been dominated by environmentalist explanations that downplay or dismisses the importance of biology. As recently as 2007, a survey of liberal and radical criminologists found they attribute crime mainly to such causes as an unfair economic system, lack of education, peer influence, and bias in law enforcement.

One consequence of neglecting biology is that criminologists treat sex and crime as separate and unrelated, at least when not discussing specifically sexual crimes such as rape. Yet a strong correlation exists between criminality in general — not just sex crimes — and a certain pattern of sexual behavior. Criminal offenders show an earlier onset of sexual activity than non-offenders, have more sexual partners, father children by more women, are more likely to have sexually transmitted diseases, are less likely to get married and, if married, are more likely to divorce. The more criminal convictions a man has, the stronger these associations become.

This is because a tendency to pursue irresponsible sexual adventures is driven by the same short-run hedonistic traits that define criminality. Such traits include sensation-seeking as well as low levels of empathy, intelligence, self-control, and conscientiousness. Any serious effort to explain these traits leads straight to biology: brain functioning, genetics, and natural selection. Researchers have already identified specific gene variants that predict high levels of both sexual activity and antisocial behavior.

The strawman of biological determinism

Mainstream criminologists dismiss these arguments as “biological determinism,” accusing their proponents of thinking all behavior is preprogrammed by our genes and uninfluenced by environment. This is an obsolete understanding of DNA.

Genes never dictate specific behavior, personality, or emotion. All they “determine” is amino acid sequences within certain proteins. The route from these proteins to actual behavior is no expressway, but more like a “winding, detour-ridden back road riddled with potholes.” The genetic basis of human behavior is only probabilistic, never deterministic.

Furthermore, gene expression is heavily influenced by environment. As biologist Matt Ridley puts it, genes “may direct the construction of the body and brain in the womb, but they set about dismantling and rebuilding what they have made almost at once in response to experience.” The author of this book, Anthony Walsh — who teaches criminal justice at Boise State University — writes that “the genome is a reactive system rather than a controlling system. Without an environment, genes have no place to go because they depend on an environment to activate them.” There is now an entire subdiscipline called “epigenetics” devoted to studying the many processes that alter gene activity without changing DNA. Many of these processes involve environmental input: the circumstances and situations a person encounters in life affect gene transcription.

Experience also plays a role in wiring the brain:

Brain imaging studies reveal that the prefrontal cortex undergoes a wave of synaptic overproduction just prior to puberty, which is followed by a period of pruning during adolescence and early adulthood. The selective retention and elimination of synapses rely crucially on experience-dependent input from the environment.

In this way, the human brain is in part custom designed for dealing with the sort of environment it meets with as the individual comes of age.

In sum, the old divisions of “nature or nurture,” “genes or environment,” are hopelessly out of date. All competent biologists know this, and it is past time social scientists learned it. As Prof. Walsh notes, everyone will gain from incorporating the insights of different disciplines: “For social scientists, understanding genetics will take them closer to understanding environmental effects, and for biological scientists, understanding the environment will take them closer to understanding genetic effects.”

Evolution and the sex ratio in crime

As long as it refuses to take evolutionary biology into account, criminology remains stuck at the lowest level of scientific inquiry: observation and description. Only biology can take the discipline to the next level of grasping causes. For example, perhaps the most reliable pattern in all of criminology is that men always and everywhere commit more crime than women, but mainstream criminologists have no convincing explanation for this. They can attribute it only to socialization — to parents and teachers treating boys and girls differently. But this gets causality backwards: parents and teachers treat boys and girls differently because they are different.

The true explanation lies in the different reproductive strategies of men and women, with men drawn to maximize mating opportunities while women are more cautious in mating choices:

The inherent conflict between the reckless and indiscriminate male mating strategy and the careful and discriminating female strategy drove the evolution of traits in males such as aggressiveness and, relative to females, lower levels of empathy and constraint that help males overcome both male competitors and female reluctance.

Since an infant’s survival depends far more on its mother’s than its father’s survival, women have developed a strong aversion to risk: “Greater fear responses account for the greater tendency of females to avoid potentially violent situations and to employ indirect and low-risk strategies in competition for mates and dispute resolution.” Over human evolutionary history, risk-averse women have had greater reproductive success, and have therefore passed on that trait to their daughters.

Men, on the other hand, can maximize their reproductive success by competing directly against other men for status and resources, a high-risk, high-reward strategy. They benefit from being bold, enterprising, and aggressive. In the primary human environment of evolutionary adaptation — the hunter-gatherer band — the connection between high crime rates and mating is obvious. As psychologist Judith Harris has observed:

Almost all the characteristics of the “born criminal” would be, in watered-down form, useful to a male in a hunter-gatherer society and useful to his group. His lack of fear, desire for excitement, and impulsiveness made him a formidable weapon against rival groups. His aggressiveness, strength, and lack of compassion enable him to dominate his groupmates and give him first shot at hunter-gatherer perks.

Those perks are chiefly economic resources and mating opportunities. Mr. Walsh writes that, “Of course, such traits can easily overshoot their optimum and become liabilities,” especially “when exercised freely in evolutionarily novel modern societies.”

Women can steal and be aggressive, but as one criminologist notes: “they rarely do both at the same time because the equation of resources and status reflects a particularly masculine logic.” Studies of female thieves do not indicate that achieving social dominance is among their motives, nor do they wants to gain reputations as “badasses,” as young male delinquents often do.

Evolution and the age-crime curve

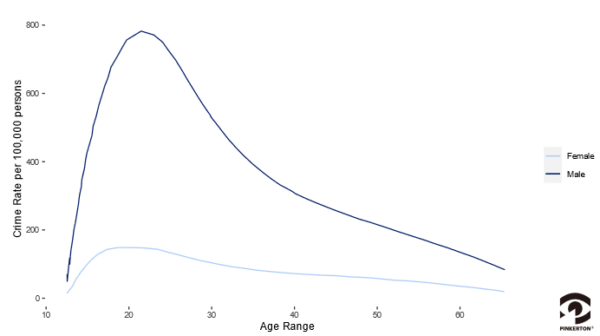

A second pattern in criminology almost as reliable as the sex ratio is the age-crime curve which “shows a sharp increase in offending beginning in early adolescence, a peak in mid-adolescence, a steep decline in early adulthood, and a steady decline thereafter.”

Mainstream criminologists can attribute this only to “peer influences,” but as the author points out, “they do not inform us why these peer influences become more salient during adolescence, and why [they] are typically antisocial rather than prosocial.” Comparative primate studies:

have shown that [primate] adolescents share with human adolescents the tendency to become overly sensitive to rewards, risk-taking, sensation-seeking and novelty. From an evolutionary perspective, the purpose of these tendencies is to compel the animal to leave the nest to find a mate from another troop.

Neurologists are coming to understand the associated brain mechanisms, as explained in a paper cited by Prof. Walsh:

The propensity during adolescence for reward/novelty seeking in the face of uncertainty or potential harm might be explained by a strong reward system (nucleus accumbens), a weak harm-avoidance system (amygdala), and/or an inefficient supervisory system (medial/ventral prefrontal cortex).

Prof. Walsh writes:

Adolescence is accompanied by changes in the ratios of excitatory to inhibitory neurotransmitters. The reward- and excitation-related transmitters dopamine and glutamate peak while the inhibitory transmitters gamma-aminobutyric acid and serotonin are reduced. . . . While parents may decry adolescent behavior, it is how natural selection has designed them to leave the nest and produce the next generation.

One understandable by-product, especially in cities, is a high crime rate among young adult males.

Crime and Life History Theory

Life History Theory proposes that living organisms face a trade-off between mating effort and parenting effort. In a dangerous, unstable environment, an animal best reproduces by quickly having as many offspring as possible but devoting little or no effort to nurturing them. This is called an ‘r’ reproductive strategy, part of a fast life history. In a challenging but stable environment, animals do better to produce fewer offspring but invest in them. This is called a ‘K’ strategy, part of a slow life history.

Humans are the most ‘K’-selected animals in nature, but not all subgroups of our species are equally K. The male strategy of maximizing mating opportunities is more ‘r’-selected than the female strategy of careful mate selection. There is also a spectrum of life-history traits within men that distinguishes “cads” from “dads.” Differences in sexual attitudes, desires, and behaviors can be plotted on the so-called sociosexual scale which forms:

a continuum from restricted (i.e., fewer sexual partners, agreement with conventional sexual attitudes, and a preference for long-term relationships) to unrestricted (i.e., larger number of sexual partners, permissive sexual attitudes, and a preference for short-term over long-term relationships).

Researchers have found “mating effort highest among manipulative, self-centered individuals, [while] parenting effort characterized those who endorsed sexual commitment and higher empathy.”

The relevance of Life History Theory to criminology is that crime correlates strongly with a fast life history:

More than 35 years ago, Lee Ellis (1988) reviewed numerous studies showing that individuals with serious criminal histories were high on fast life history traits. Ellis’ literature review provided abundant evidence that criminals had shorter gestation periods, faster maturation, earlier onset of sexual activity, a greater number of sexual partners outside of a bonded relationship, unstable parental and partner bonding, low parental investment (high rates of child abuse, neglect, and abandonment), and shorter life expectancy.

Crime can in part be seen as an anachronistic survival of a way of life that would have been adaptive in our ancestral environment before agriculture. In Prof. Wash’s words:

Violence (at least credible threats of violence) is intimately related to reproductive success in almost all animal species as a way to gain access to resources and females. Reacting violently when some brute tries to steal your bananas, your cave or your wife could be very useful in evolutionary environments when you just couldn’t call 911 to have the police settle your problem. Having a reputation for violence would be even better because others would avoid your bananas, cave and wife in the first place. In environments in which one is expected to take care of one’s own beefs, violence or the threat of violence works to let any potential challenger know that it would be in his best interest interests to avoid you and your resources and look elsewhere.

A propensity to retaliate violently against all threats is part of a fast life strategy and is “advantageous among humans inhabiting harsh and unpredictable environments characterized by high levels of predation.”

The modern urban slum is therefore like the environment of evolutionary adaptation in hunter gatherer bands. High mortality and resource scarcity lead to and reinforce a faster life history strategy. Boys growing up in a high-crime slum see plenty of violence, which makes them feel vulnerable. They react by resorting to preemptive violence themselves, seeking a “badass” reputation that will deter aggression — often at great risk to themselves. They create a feedback effect, inviting more of the hostility they seek to guard against. The world becomes “a dangerous and hostile place, setting in motion a vicious cycle of negative expectations and confirmations.”

A similar feedback pattern emerges to perpetuate and reinforce the tendency to fatherlessness in such environments:

Evolution has built plasticity into our brains and genomes so we can adopt different reproductive strategies facultatively based on childhood experiences. Early childhood is a sensitive period in which future reproductive strategies are calibrated by stressors relating to interpersonal relationships, with father absence being a major stressor. Father absence is correlated with the acceleration of the early onset of puberty. Children will adopt an unrestricted [or ‘r’ mating] strategy if they perceive interpersonal relationships as fleeting, unreliable, and emotionally unrewarding.

Feedback loops of this kind make slums very difficult to reform.

Genome-wide association studies have found genetic correlations between various measures of reproductive effort and antisocial behavior. In the words of one study from 2018:

Our genetic correlation analyses demonstrate that alleles (gene variants) associated with higher reproductive output (i.e., faster life history styles) were positively correlated [0.50] with alleles associated with antisocial behavior, whereas alleles associated with giving birth later in life were negatively associated with alleles linked to antisocial behavior [—0.64].

The neurology of crime

Much human behavior is governed by a “tug-of-war within us as we seek rewarding opportunities while avoiding punishing consequences.” No analysis of this process would be complete without some discussion of the brain.

What researchers call the behavioral approach system (BAS) motivates us to seek pleasure. “It is primarily associated with dopamine (the ‘happy hormone’) and with mesolimbic system pleasure centers rich in neurons that respond to dopamine.” The BAS can be thought of as our behavioral accelerator pedal.

But we must also avoid danger and pain. Avoidance can be instinctive or, in humans, a product of reflection. For instinctive responses to sudden threats we have what researchers call the fight/flee/freeze system (FFFS) which is part of the autonomic nervous system that governs unconscious bodily processes.

Humans must also weigh the social aspects of reward-seeking and pain-avoidance. For this purpose, we have a behavioral inhibition system (BIS) based primarily in our prefrontal lobes, sometimes known as the “social brain.” The BIS “enables us to negotiate relationships, understand the thoughts, feelings, and intentions of others, and cooperate in securing resources and defending the group. We learn to seek our pleasures with temperance and prudence thanks to the BIS.” The prefrontal lobes involved in the BIS operate consciously. They are unique to humans, were the last brain areas to evolve, and the last to mature in individuals.

The BIS and FFFS are both concerned with avoidance, and hence overlap to some extent: both involve the amygdala (anxiety) and the hippocampus (memories of similar situations), as well as the inhibitory neurotransmitter serotonin. Together, they can be thought of as our behavioral brake pedal.

Criminals tend to have “a dominant BAS, a weak BIS, and/or a hypoactive FFFS.” Their weak avoidance systems may be related to low levels of serotonin activity, which lead to aggression and impulsiveness:

One of criminology’s most invoked causal variables — low self-control — is highly influenced by serotonin functioning, as is negative emotionality. Negative emotionality is the tendency to experience many situations as aversive and to react to them with irritation and anger. Because both traits are underlain by low serotonin functioning, [criminologist Robert Agnew has] contended that aberrant serotonergic functioning may be a heritable diathesis [predisposition] for a personality style involving high levels of negative affect and low levels of constraint [self-control], which generates in turn a vulnerability to criminal behavior.

There is a gene known as 5-HTTLPR which governs how serotonin is transported and recycled within the body, and it comes in a common “long” variant and less common “short” variant. The “short” variant reduces gene expression, causing the BIS to function less efficiently. People with this short variant engage in more risky sexual behavior.

The physical basis of psychopathy

The author writes:

Nowhere is the link between criminality and hypersexuality more clearly seen than in the psychopath. He is both the quintessential criminal and the quintessential cad. The central characteristics of psychopaths, such as emotional coldness, lack of empathy and guilt, high risk-taking, inability to delay gratification, present orientation, and a lack of commitment and loyalty, are suited to both career criminality and successful short-term mating effort. A core part of psychopathy thus includes having many impersonal sexual encounters. Psychopathy affects approximately 1% of the general population but is present in 15-25% of the prison population.

Electroencephalography (EEG) studies find distinctive features in the brains of psychopaths. In one such study:

psychopaths and non-psychopaths are presented with a list of emotionally neutral and emotionally laden words. When presented with emotionally neutral words (e.g., apple, cup) both show a small EEG spike indicating they have recognized the word and visualized an apple or cup. When presented with emotionally laden words (cancer, death, mother), non-psychopaths show a much higher spike indicating that they have recognized the word and [paired] the cognition with emotion. When psychopaths are presented with the same emotional words, they process them the same way they processed apple or cup. That is, they recognize the words intellectually but fail to involve the emotions.

Brain imaging studies have linked psychopathy to specific areas of the brain, especially the amygdala and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. Impairment of these regions offers the most plausible explanation for “why although psychopaths can think rationally, they fail to integrate their thinking with feeling. All studies agree that in psychopathy there is a decoupling of the cortical and subcortical structures that tie the rational and the emotional structures together.”

Sex ratios and crime

The sex ratio is the number of males in a population divided by the number of females. The operational sex ratio refers to potential partners — those in the mating game.

When women are plentiful — a low operational sex ratio — men revert to polygyny. Both men and women are more likely to remain unmarried, and illegitimate births increase. The divorce rate is high, but the remarriage rate is high only for men. Men compete for women, as they always do, but for short-term encounters “in locations such as bars that are likely to lead to violence.” Rates of murder, rape, and prostitution increase. Children grow up in poor, fatherless homes, and have high levels of depression, behavioral problems, drug abuse, promiscuity, and suicide. As they come of age, they often join criminal youth gangs.

High operational sex ratios give women more control over mating, which they use to insist on male commitment. Men get married, society is more stable, and crime goes down. If the sex ratio gets too high, however, an excess of bachelors with too much time on their hands also leads to the formation of criminal gangs. Moreover, women become spoiled and excessively materially demanding, and men resort to crime to get the resources needed to attract them. An even or mildly high female-to-male sex ratio is the most favorable for social stability and high-investment parenting.

In Too Many Women (1983), their study of low sex ratio societies, social psychologists Guttentag and Secord write: “American blacks present us with the most persistent and severest shortage of men in a coherent subcultural group that we have been able to discover during the age of modern censuses.” The operational sex ratio among blacks is exceptionally low because:

a greater proportion of Black males are incarcerated in prisons and mental institutions than males of any other racial or ethnic group. Additionally, Black males of all ages die at higher rates than white or Asian males from homicides, alcoholism, drug overdoses and accidents.

A literature review quoted by Prof. Walsh notes:

Several studies of African American communities describe black women’s distrust of black men, and their assumption that most black men are “naturally” or inherently bad, sinful and untrustworthy — particularly in their relationships with black women.

The author also cites a survey of married women that found only 36 percent of lower-class black women would marry again if they had to start their lives over; the figure for white women was 100 percent. One important factor Prof. Walsh does not mention is the effect of American welfare law, with its “man in the house” rule limiting benefits to fatherless families. Obviously, this creates a powerful incentive to start and maintain such families. Some combination of a naturally fast life strategy in blacks and the perverse incentives of welfare policy have created massive fatherlessness among black Americans, and it is the proximate cause of much black criminality.

Conclusion

Although Prof. Walsh deals with race at any length only in his final chapter on sex ratios, all of Sexuality and Crime demonstrates the importance of biology as an explanatory factor in the human sciences. The hold of the environmentalist model on the minds of mainstream criminologists must be very strong for them to forego the explanatory power the author draws from the biological sciences. If Anthony Walsh has no such ideological inhibitions, it may in part be because he worked as a police officer and probation officer for many years before turning to academic criminology in his forties.