Renaud Camus is a French novelist and essayist who coined the term the “Great Replacement” in 2011 and has been in hot water ever since. On May 6, 2023, at the behest of the Vlaams Belang party, he delivered a speech entitled “What is the Great Replacement?” before the Flemish parliament in Brussels. An English translation of Mr. Camus’s remarks, read by someone else, is available as an audio file from Legatum Publishing.

The speech is highly interesting in that not only does Mr. Camus articulate very precisely what the Great Replacement is, he also exposes, in striking terms, the dishonesty of all attempts to deny that it is occurring. Still more interesting is Mr. Camus’s attempt to situate our understanding of the Great Replacement within a much broader intellectual context.

Mr. Camus argues, in fact, that the Great Replacement is an expression of the fundamental metaphysical assumptions of modern industrial civilization itself. The basic ideas of the speech are an encapsulation of the arguments he presents in his 2022 book La Dépossession: ou Du remplacisme global [Dispossession: or On Global Replacism].

At the beginning, Mr. Camus states that “It has gotten to the point where we could proceed in the negative and define . . . the expression ‘Great Replacement,’ by everything that the Great Replacement is not and by everything that its adversaries — who oppose the name but support the thing — say it is.” To begin with, Mr. Camus claims, the Great Replacement is not a “theory.”

The establishment likes to refer to the Great Replacement as a “conspiracy theory.” Indeed, Mr. Camus’s Wikipedia entry calls him a “French novelist and conspiracy theorist.” But the Great Replacement is no theory at all; it is a reality. The systematic replacement of indigenous European peoples by more fertile and aggressive foreigners is happening. Further, it is happening as a direct result of government policy, and with the knowledge and blessing of the policymakers.

Every day, Europeans are confronted with evidence that the Great Replacement is quite real. Mr. Camus writes:

In millions of buildings, thousands of neighborhoods, streets, schools, classrooms and class photographs, athletic teams, hundreds of towns, regions, provinces, and in numerous states, nations, governments, there was one people and now there is another, or several others; there was a civilization, faces, clothes, habits, lifestyles, ways of being and understanding each other, and now there are others, not necessarily superior, but which have indeed replaced them.

To demand evidence that the Great Replacement is occurring is akin to demanding evidence of an earthquake, a tsunami, or an epidemic, Mr. Camus says. Imagine the absurdity of FEMA officials showing up in Asheville, North Carolina, and demanding that residents prove the city had been hit by Hurricane Helene. Mr. Camus draws an even more apt parallel: “To demand from a Western European, in 2023, evidence of the change of people and civilization in which he is daily immersed, makes no more sense or decency than to demand of a Frenchman, a Belgian, or a Dutchman, in 1943, evidence of the German occupation.”

Mr. Camus suggests, furthermore, that speaking of the “theory” of the Great Replacement is like speaking of the “theory” of the gas chambers. He pushes this parallel, suggesting that there is a moral equivalency between Holocaust “denialism” and denial of the Great Replacement. After all, Mr. Camus suggests, the Great Replacement is also genocide: genocide “by replacement.”

A significant difference between the two forms of denialism, however, is that Holocaust denialism has almost entirely been the work of individuals viewed by most as marginal cranks. By contrast, the denial of “genocide by replacement” is pushed by “popes, kings, presidents of the Republic, presidents of councils, prime ministers, ministers, party leaders, members of parliament, bankers, company directors, magistrates, professors, teachers, and journalists, journalists, journalists.”

Mr. Camus refers to all these people collectively as the “Denialist-Genocidal Bloc.” Earlier, I quoted him saying that these individuals “oppose the name but support the thing.” In other words, while they support the Great Replacement, they have made it taboo to name the phenomenon or to speak about it. The Denialist-Genocidal Bloc “calls any resistance to its crime hatred just as it calls any questioning of the nature of this crime a conspiracy theory.”

The Great Replacement, in other words, is the genocide that dare not speak its name. The perverse logic of the Denialist-Genocidal Bloc does, however, permit us to speak openly of the Great Replacement — but only if we express approval of it . In an act of ideological contortionism that would shock Orwell, supporters of the Great Replacement will readily admit it is real if one welcomes it — and just as readily deny it is real if one expresses disapproval.

Mr. Camus writes:

It is perfectly fine to acknowledge it as a reality if one celebrates it. If, on the other hand, you do not like the Great Replacement, then it does not exist, you are the one inventing it and you are a fascist, a racist and a propagator of conspiracy theories. If you like it, it exists, and it is an opportunity for France, an opportunity for Flanders, a blessing for Belgium, a lifeline for Europe; and you are a benefactor of humanity.

Just how has Europe arrived at the genocidal program of the Great Replacement? Why is the entire establishment pushing this “genocide by substitution” and simultaneously denying it? Mr. Camus offers two answers, one cultural and historical, the other metaphysical. The cultural-historical answer has to do with the legacy of the Second World War. Mr. Camus refers to what he calls “Adolf Hitler’s Second Career,” or the ongoing, negative influence of Hitler in the post-war world.

Supporters of the Great Replacement hold that it is morally necessary in order to atone for the evils of Nazi racism and genocide. Further, they believe that it is not only Germany that is implicated in these evils, but all of Western Civilization. The West has a long, dark history of racism and colonialism. Thus, all Westerners deserve to get diversity, and to get it good and hard. Indeed, their position is basically that white people deserve extinction.

The result of this zeal to cleanse ourselves of Hitlerism looks like it may very well be the destruction of Western Civilization itself. It is a process that presents us, moreover, with multiple layers of irony. For example, Mr. Camus points out that mass migration of Muslims into Europe means a mass influx of antisemitism.

It has, he says, “created a world where the Holocaust often, in several classrooms, can no longer be taught” and where Jews are forced to “evacuate entire neighborhoods, towns, and regions from which they were not driven even in the dark years” (presumably, the dark years of the Second World War).

In a further irony, “anti-racism” has become the opposite of what it was originally intended to be. Whereas it had been the protector of races and racial differences, it has now become the “destroyer of all races.” Presumably, Mr. Camus is referring here to the well-known fact that multiculturalism has the inevitable result that races blend together both physically and culturally and eventually lose their distinctiveness.

Yet another irony is that “anti-racists” are now calling for the disappearance of races “on the grounds that they do not exist.” An ideology that had originally set out to combat discrimination on racial grounds now declares that there is nothing against which to discriminate, since racial difference is a “myth.” At the same time, we are enjoined to “celebrate” these non-existent differences.

The goal of “anti-racism” and of the Great Replacement does indeed seem to be the erasure of all differences and the creation of a single, undifferentiated humanity. This observation brings us to Mr. Camus’s metaphysical explanation of the Great Replacement, which is the aspect of his speech that readers will probably find most original and surprising.

Early in the text, Mr. Camus states that “The Great Replacement, colossal as it is, since it affects dozens of nations and takes place on at least three continents, is only a tiny part of what global replacism accounts for.” What he calls “global replacism” is largely the subject of his book La Dépossession.

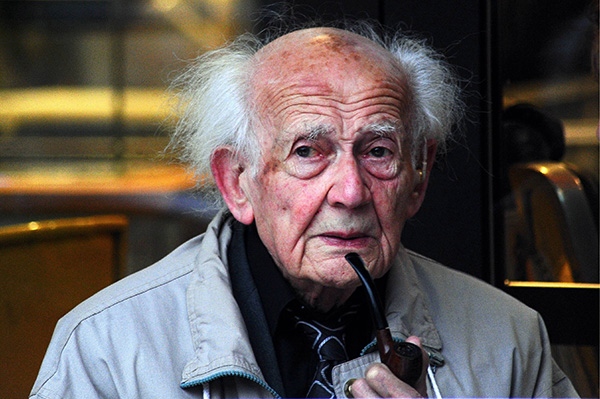

Mr. Camus argues that the Great Replacement is possible because it flows from modern technological civilization’s deepest assumptions about the nature of reality — its metaphysics, in other words. Mr. Camus cites the Polish-Jewish philosopher Zygmunt Bauman (1925–2017) as the major influence on his analysis. His real debt, however, is to the German philosopher Martin Heidegger (1889–1976) who was, in fact, a major influence on Bauman. The positions Mr. Camus takes here on the nature of modernity are thoroughly Heideggerian.

It was Heidegger’s belief that the different stages of civilization in the West are marked by different understandings of being; i.e., different conceptions of what is or of what exists. Each historical period has its own metaphysics. Thus, Heidegger could speak of a “history of metaphysics” (Geschichte der Metaphysik) or “history of being” (Seinsgeschichte). For example, Heidegger noted that to be in the Christian Middle Ages essentially meant to be an artifact of an omnipotent creator.

For Heidegger, how cultures become animated by particular metaphysical positions, and how those positions change, is fundamentally mysterious. He does not believe that philosophers create them. Instead, like Hegel, Heidegger believes that philosophers give expression to the fundamental Zeitgeist — the “spirit of the times” — that is already in the air before they ever set pen to paper.

If we ask Heidegger about the metaphysics of modern technological civilization, he will answer that we moderns live our lives as if we believe that everything that exists is nothing more than raw material for manipulation and exploitation. Fundamentally, in other words, we believe that everything is merely “stuff” that waits upon us to confer identity upon it — to transform it in the service of satisfying human desires and aspirations.

In modernity, furthermore, we believe that there are no limits on our ability to transform the world, as well as ourselves. Everything is seen as infinitely malleable. These beliefs are seldom reflected on, and almost never stated openly.

For Heidegger, the spirit of modern technological civilization is so totalizing that we even come to see each other as raw material to be transformed according to our schemes. We might name Communism as an obvious example of a philosophy that sought fundamentally to “make over” humanity. Heidegger, however, sees the same spirit at work in capitalism.

Under capitalism, everything becomes a replaceable, recyclable “commodity” — and this includes human beings themselves. Men become mere “consumers” manipulated by producers to desire whatever is offered to them, and qua consumers, they are entirely replaceable. Everywhere in the modern world, for Heidegger, there is a will toward uniformity, replaceability, recyclability.

Echoing Heidegger, Mr. Camus states at one point in his speech, “The theory of global replacism is based on the observation that replacement, the act of replacing, is the central feature of modern and contemporary societies.” The modern imperative is “replacism,” to use Mr. Camus’s neologism: everything must be replaceable. What replaces has, in general, the advantage of being “simpler, more abundant, easier to manufacture and, of course, cheaper.”

Mr. Camus offers us many examples of this, some of them quite familiar. Stone is replaced by concrete. Linen and silk are replaced by synthetic fabrics. The countryside is replaced by suburbs and cities. His examples involving the replacement of human beings are far more disturbing. “Indigenous peoples [are replaced] by diversity, residents by BnB tenants, men by women, men and women by robots, robots by robotized men and women, humanity by a deranged post-humanity, intelligence by artificial intelligence.”

A humanoid robot performs during the Light of Internet Expo, a part of 2024 World Internet Conference Wuzhen Summit, on November 19, 2024 in Jiaxing City, Zhejiang Province of China. (Credit Image: © Imago via ZUMA Press)

Mr. Camus continually echoes Heidegger’s claims about modernity’s drive toward uniformity and the erasure of all distinctions. He notes that one of the most recent, and extreme, manifestations of this is progressivism’s attempt to convince us that men and women do not really exist, that all apparent differences are merely “socially constructed.” If men and women can be anything we say that they are — if men can have vaginas and women penises — then men and women become interchangeable.

Modern civilization is progressively stripping individuals and groups of everything that makes them unique and distinctive — especially in the case of distinctions that have traditionally been seen as inherent, “natural,” or eternal. All of this has been sold and widely accepted as “liberation.”

As Mr. Camus says, “The trans is king of the world.” In other words, the new man of the modern West is transexual, transracial, transnational, transcultural, transfamilial, and much else. He/she/it has been liberated from all traditional forms of identity.

Eventually, as Aleksandr Dugin has predicted, the elites will be selling us on the idea that the new frontier is liberation from human nature itself (“transhumanism”). Indeed, it does seem inevitable that any day now, our intellectuals will declare that belief in a fixed and eternal human nature is an intolerable tyranny. (In fact, they already did this long ago.)

“In order to be fully interchangeable,” Mr. Camus writes, “the replaceable human being must be dispossessed one by one of all his attributes, everything that combined to make him unique: name, class, race, sex, culture, origin, etc. The industries of humanity are working incessantly to mass-produce this supreme product, what I call UHM, Undifferentiated Human Matter.” To be liberated from all traditional forms of identity is, in fact, to be liberated from being anything at all.

According to Mr. Camus, it is this drive to replaceability and uniformity — this modern metaphysics of the real as replaceable — that has given rise to the Great Replacement itself. His words are worth quoting at length:

The next stage is the one we are experiencing, which makes the Great Replacement possible: replaceable man, his total interchangeability, his liquefaction so well analyzed by Bauman, his dispossession. Reduced to the state of UHM by the successive eradication of all his attributes, the human being of . . . global replacism is himself transformed, from the producer and consumer he already is, into a product. The most valuable product is the consumer. The old peoples of the old continent have the wisdom not to produce enough to satisfy the Machination [Heidegger’s term — in German, Machenschaft — for modernity’s spirit of exploitation]. So it replaces them with more (re)productive races. How can the latter consume, you say, when they have no money? Don’t worry, they’ll get yours. Just as social housing is but a code name for racial housing, so-called social transfers are nothing more than racial transfers. And the newcomers will always need housing, roads that lead to it, transport, schools, although they do not always seem to benefit much from them, hospitals and nurseries for our replacers.

The logic of replacism is inexorable. If everything is replaceable, then why shouldn’t entire peoples be replaceable? What does it matter who lives in France, so long as they reliably consume?

The differences between populations present serious problems for multinational capitalists, who must adjust their product lines and advertising according to cultural differences in taste, mores, and religious convictions. It would be much easier if such cultural differences ceased to exist. To achieve this goal, a two-pronged strategy is being pursued: the simultaneous promotion of “consumer culture” and “diversity.”

We have all noticed that our own people increasingly lack any ties to history (about which they know almost nothing), to place, and to both folk culture and “high culture.” Instead, a consumer culture dominates in which individuals in different geographic locations — at one time characterized by strong cultural differences — yearn for, consume, and discuss the same mass-produced commodities.

The establishment promotes this consumer culture as promising a kind of pax aeterna. What will there be to fight about when humankind’s most exalted aspiration is the freedom to acquire more consumer goods? A further step is the promotion of “diversity.” As noted earlier, pursuing a policy of multiculturalism is an extremely effective way to blur racial and cultural differences. The ultimate result of this two-pronged strategy would be a kind of undifferentiated “generic human,” without distinctive ethnic or cultural identity.

Thus, it turns out that “diversity,” as an ideological imperative, really means its exact opposite: uniformity. “Diversity” is a means for promoting uniformity. Of course, the elites are counting on the idea that racial and cultural differences can be peacefully blended away, thanks to the supposedly universal and irresistible attractiveness of Western consumer culture.

This may well be a fatal error. European elites do not seem to have considered the obvious fact that the culture of the invaders has a stronger hold on the hearts and minds of men than our decadent consumer culture ever could have. No one is willing to become a suicide bomber in the cause of defending a deracinated consumerism.

Those on the political Right usually see the Great Replacement as both a political problem and a technical problem. The solution is usually held to involve two stages: the acquisition of political power by the opponents of the Replacement, followed by the application of technocratic know-how to remove the replacers (e.g., remigration).

The tremendous value in Mr. Camus’s approach is that he has gone beyond the political and the technical and situated the Great Replacement within a much larger historical and philosophical context. Mr. Camus has argued that it is just one more manifestation of modern technological civilization’s relentless drive toward uniformity and replaceability; what he calls, again, “replacism.” This itself stems, as Heidegger recognized, from modernity’s metaphysical conviction that beings — all beings — are nothing more than plastic material for exploitation.

One does not need to make a choice, by the way, between Mr. Camus’s cultural-historical explanation for the Great Replacement, and his metaphysical one. They complement each other. Yes, the Great Replacement is in large measure a reaction against Hitler. But why did the reaction take this particular form? Why did it take the form of a movement that seems to seek the erasure of all distinctions between peoples?

Because, Mr. Camus would doubtless argue, everything in modernity tends toward uniformity and the erasure of distinctions. That is the spirit of the times. Heidegger became disenchanted with National Socialism when he realized that, in its own way, Hitler’s movement exhibited the same modern tendency.

The net effect of Mr. Camus’s philosophical treatment of the Great Replacement is to teach us that it is a bigger problem than we originally thought, as well as a fundamentally different problem. To be sure, on one level Mr. Camus’s approach to the matter is purely pragmatic: He does discuss political and technocratic solutions to the Great Replacement. (Unlike Heidegger, in other words, he is not simply going to “wait for being” to deliver us a new metaphysics.)

Nevertheless, Mr. Camus invites us to consider that undoing the Great Replacement and making sure nothing like it ever happens again will require us to examine our culture’s deepest assumptions. We will have to abandon the idea that beings, including human beings and their social arrangements, are infinitely malleable; that they can be anything we choose to make of them.

What is called for, it seems, is a return to the ancient convictions that beings possess intrinsic and unalterable “natures,” that there are inherent limits on the human ability to transform them, and that we attempt to transgress those limits at our peril.

Is such a return possible, or must we continue our long march into dissolution, watching helplessly as the modern madness plays itself out? This is the great question of our time.