Just over a year ago, four Pepperdine University students were killed by a speeding car on a section of Pacific Coast Highway known to Malibu locals as “Dead Man’s Curve.”

The tragic deaths of Niamh Rolston, Peyton Stewart, Asha Weir and Deslyn Williams brought the number of fatalities on the 21-mile stretch of PCH to 61 in just the last 15 years and put the highway’s dangers at the top of officials’ agendas like never before.

Amid the outcry from the community, California Highway Patrol officers were added to enforcement efforts, the governor approved speed cameras, Caltrans expedited road improvements and the city launched a public safety campaign. But a year later, some say it’s not enough.

“[Dead Man’s Curve”] is the area where it’s the most dense, it’s the highest number of pedestrians, cyclists, people, tourists,” said Damian Kevitt, a member of the local coalition Fix PCH and founder of the nonprofit Streets Are for Everyone. “And there’s a high degree of houses and commercial area [where there] shouldn’t be a speed limit of 45 miles an hour.”

At the Ghost Tire Memorial, friends place flowers for Peyton Stewart, one of the four Pepperdine students killed on Pacific Coast Highway in Malibu a year ago.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

On the one-year anniversary of the crash Thursday night, Malibu residents returned to the area to remember the four students.

Gathering at the Ghost Tire Memorial, they left flowers and small lights near tires set up like gravestones with the names of crash victims.

In 2023, there were 220 crashes on PCH, including 93 involving injuries and three that killed seven people, according to local officials.

After last year’s crash, the city declared an emergency to quickly free up funds and get to work upgrading the highway.

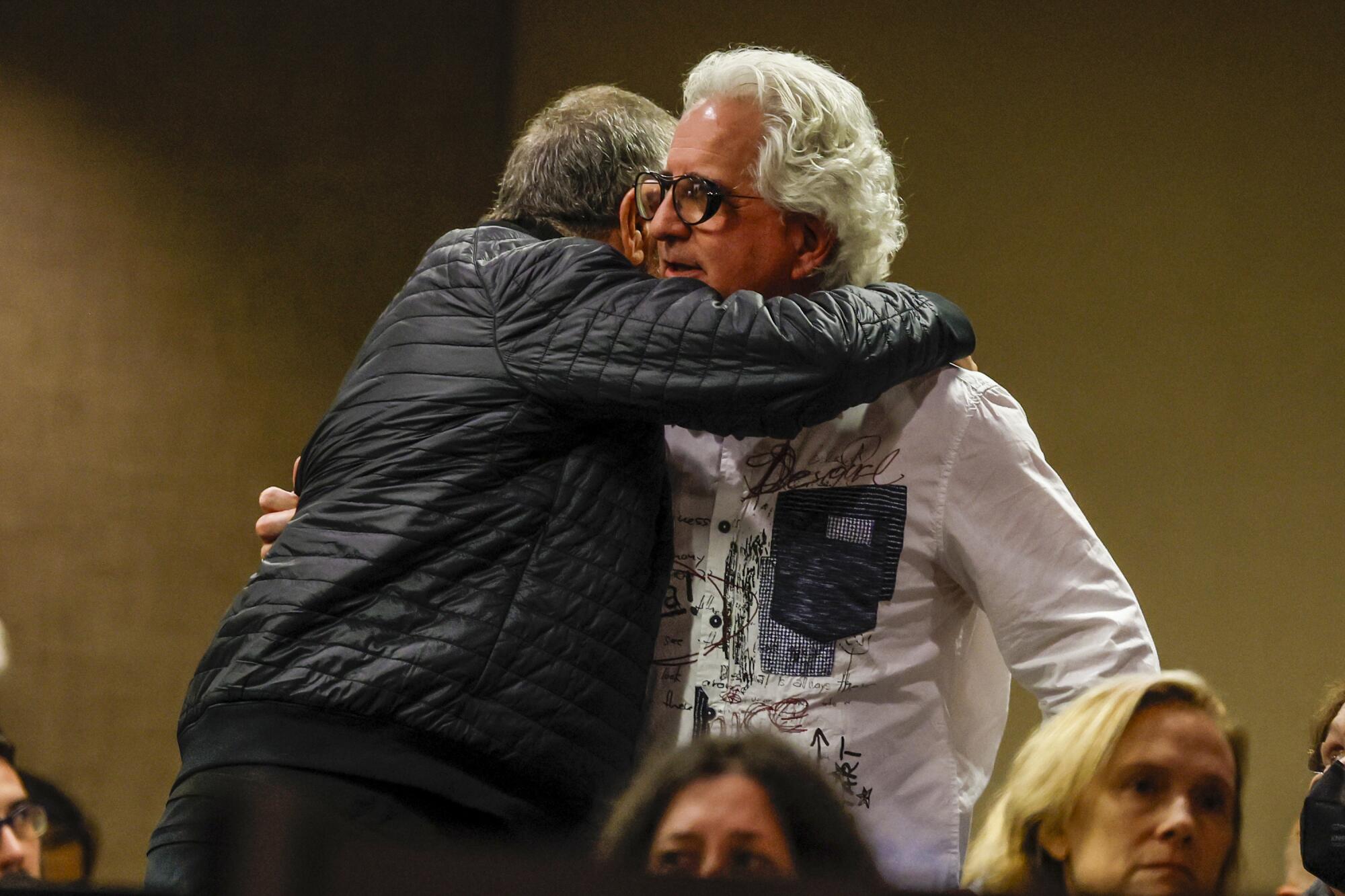

Filmmaker Michel Shane is hugged at a Malibu City Council meeting after offering his observations about dangerous traffic on Pacific Coast Highwa. Shane’s daughter, Emily, was killed on PCH in 2010.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

A traffic safety group, Streets Are For Everyone, hosts a Ghost Tire Memorial placement in memory of the four Pepperdine students killed by a reckless driver, including Asha Weir, 21.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

Over the last 12 months, Malibu has approached its PCH problem from multiple angles. It has spent $39 million on improvement projects and budgeted for an additional $8 million.

It has aimed to educate drivers, both local and tourist, through a “Go Safely PCH” campaign that informs them about the dangers of reckless driving, what’s happened on the highway as a result of it, what’s being done to increase safety and how motorists can do their part.

At the beginning of the year, the city beefed up its law enforcement presence on the road by contracting with the CHP to deploy extra officers alongside Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputies from the Malibu/Lost Hills station.

According to the station’s midyear report, law enforcement has issued almost twice as many speeding tickets this year — 3,404 — than at the same point last year, 1,865. But there was only one less crash at the halfway point of 2024 compared with 2023, with most of them speed-related, the report showed.

The city also announced a short-term win recently when Gov. Gavin Newsom signed Senate Bill 1297 into law, putting Malibu in a pilot program that would allow it to install up to five automated cameras to detect and fine speeding drivers.

“This is not the end-all, be-all; you still need that enforcement side, the education and the engineering,” said Jennifer Seeto, captain of the sheriff’s Malibu/Lost Hills station. “But this is such a step in the right direction.”

To a point, many in the community appreciate what’s been done so far, including David Rolston, Niamh Rolston’s father. Rolston told The Times he supports the citizens of Malibu and neighboring areas in their “desire to make their community a safe place to live, work and educate their children.”

Residents, classmates and friends gather for a vigil for the four Pepperdine students killed one year ago on Pacific Coast Highway.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

The families of the four victims and a fifth student injured in the crash have sued the city and other state and local agencies for their respective roles in maintaining the highway.

“Personally, I would not want anyone else to have to experience the death of a beloved family member on Pacific Coast Highway and I join with many in the belief that things can and should be changed,” Rolston said in an email.

Other families that have experienced their own tragedies are also working for change. Michel and Ellen Shane, whose 13-year-old daughter, Emily, was killed by a speeding driver on PCH in 2010, started the Emily Shane Foundation to provide scholarship opportunities for underserved middle school students as well as spread awareness about safety on the highway.

Their next event is Sunday at Pepperdine University.

Flowers sit at the 21600 block of Pacific Coast Highway near the site where four Pepperdine students were killed by a passing car.

(Robert Gauthier / Los Angeles Times)

But more needs to be done at the state level, Kevitt said, which is a challenge for Caltrans because “they’re a bureaucracy and bureaucracy does not move fast.”

He doesn’t discount the work that’s been done but added that current and future improvements will be acceptable only “when we’re not losing lives and people are not being seriously injured because of a bad road design.”

Some residents are calling on Caltrans to reduce PCH’s speed limit. The state agency had previously told The Times it is assessing opportunities to reduce the posted limit but that the most immediate short-term actions would be to install optical speed bars, conduct a road safety audit and post speed feedback signs.