The agency that oversees federal elections and campaign finance laws will allow candidates to jointly fundraise with super PACs, a move that watchdogs say will help special interests exert undue influence in politics.

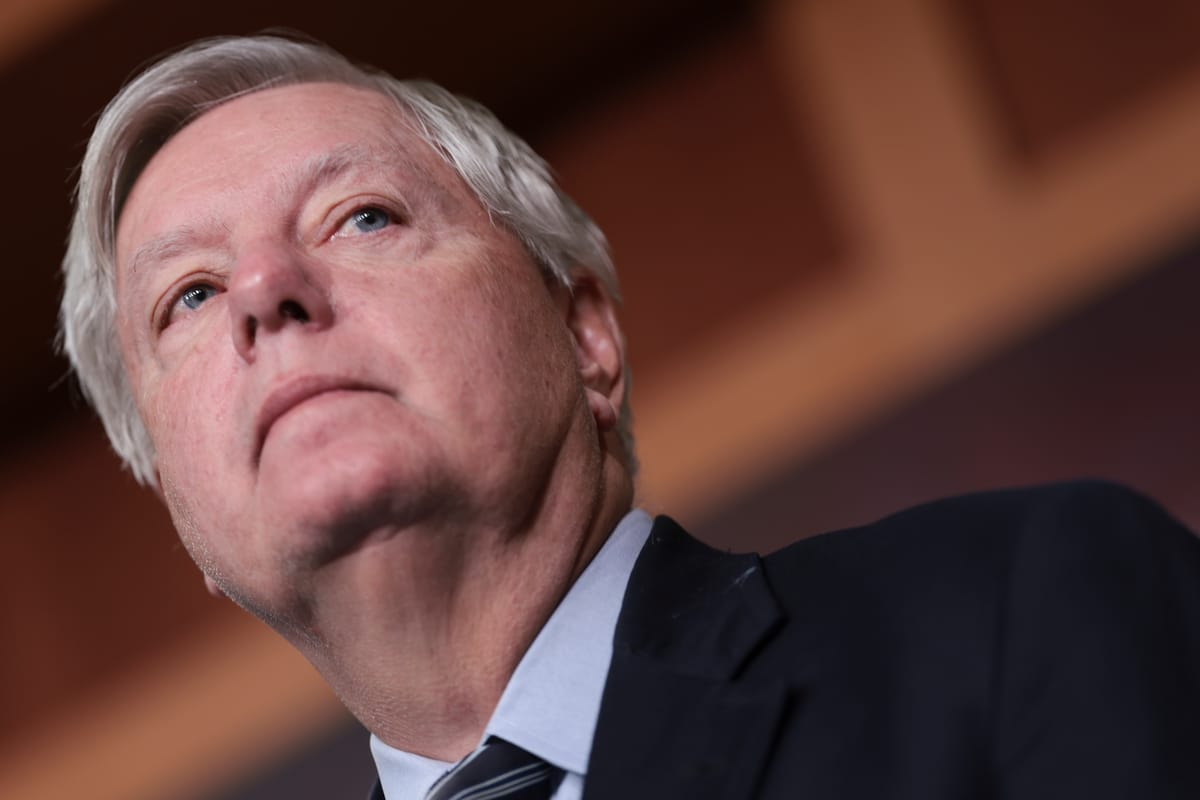

In July, lawyers for Sen. Lindsey Graham’s (R-S.C.) campaign sent the Federal Election Commission (FEC) an advisory opinion request to ask if the campaign could participate in a joint fundraising committee with a super PAC where both groups would “share data and other information as required under the joint fundraising agreement and applicable FEC reporting regulations” and “coordinate scheduling logistics” regarding fundraising events.

Super PACs, which were created after the Supreme Court’s 2011 Citizens United decision, are required under campaign finance laws to operate independently from candidate campaigns. Also known as “independent expenditure-only committees,” super PACs are allowed to raise and spend unlimited sums of money, and it’s common for them to receive multimillion-dollar contributions from individuals, businesses, and nonprofits. Preventing them from coordinating with campaigns, which can only take donations of up to $3,300 from individuals per election, is a way to stop big donors from effectively circumventing campaign contribution limits and potentially corrupting politicians.

Last Thursday, the FEC approved the Graham campaign’s request to add a super PAC to its joint fundraising committee because, it said, the campaign attested in its proposal that it would not engage in financial transactions that violate campaign contribution limits and would not coordinate with the super PAC.

“Last week’s opinion defied any common-sense meaning of ‘coordination,’ much less the definitions spelled out in federal campaign finance laws and the FEC’s own regulations,” said Shanna Ports, senior legal counsel of campaign finance for the nonprofit watchdog Campaign Legal Center. “Despite the requestor admitting that the joint fundraising venture would involve the campaign and super PAC fundraising through a shared political committee, exchanging data, and producing communications together, the FEC said no coordination would occur.”

“We will likely start to see the effects of this decision this election cycle, and it will be regular voters, whose voices are drowned out by big money in politics, who will suffer,” said Ports.

Graham’s campaign did not state in its request which super PAC it wants to jointly fundraise with, but it is likely referring to Security Is Strength, a super PAC tied to the pro-Graham South Carolina Conservative Action Alliance that has spent more than $17 million supporting the senator’s re-election efforts over the years. Security Is Strength’s biggest donors have included two “dark money” nonprofits—the Government Integrity Fund and the American Exceptionalism Institute—as well as wealthy individuals including Miriam Adelson, Craig Duchossois, and Helen Schwab. Sen. Graham will next be up for re-election in 2026.

Though the Graham campaign may become the first campaign to work with a super PAC in a joint fundraising arrangement, many have tested the legal limits over the years on their interaction with super PACs. In 2020, Democratic presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg was a guest at an event hosted by the nonprofit affiliate of a super PAC that was making independent expenditures to support his campaign. Earlier this year, a super PAC backing the presidential campaign of Robert F. Kennedy Jr. received millions of dollars in what it called “bridge funding” from a security consultant who was also the Kennedy campaign’s largest vendor. Candidates routinely place conspicuous red boxes containing text about their messaging goals on their websites as a way to communicate to super PACs about what kind of language they would like them to use in ads.

The Graham campaign’s request said that the senator, his campaign, and any of their agents would “not discuss the nonpublic campaign plans, projects, activities, or needs of Senator Graham or his campaign with any Super PAC participating in the joint fundraising committee.” In a comment, lawyers for Elias Law Group working on behalf of the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee and Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee argued that the request provides no explanation for how a super PAC that is part of the joint fundraising committee would prevent itself from obtaining or using nonpublic information.

“There is no mention of the Super PAC adopting and implementing any protocol that could protect against any unlawful coordination,” the Elias Group lawyers wrote. “There is no discussion of how the Super PAC would block the flow of material nonpublic candidate and party information, including plans, projects, activities, or needs of either, from reaching staff working to create, produce, and distribute the Super PAC’s other public communications.”

The opinion was passed by a 4-1 vote of the commission, with one abstention, during an Aug. 29 meeting. The lone opposing vote was Vice Chair Ellen Weintraub, who issued a dissenting statement calling it “a classic example of not seeing the forest for the trees.”

“Unfortunately, the Commission has already created far too many holes in what should be a solid wall dividing candidates and their committees from the super PACs that support them,” Weintraub wrote. “Because I am unwilling to pull another brick from that essential barrier, I respectfully dissent.”

For years, the FEC’s six commissioners have been deadlocked on their decision making, with the three Democrats on the commission and the three Republicans consistently disagreeing. But that has changed in the past couple years as Biden nominee Dara Lindenbaum has occasionally sided with Republicans on matters, including on the Graham advisory opinion. Lindenbaum has also joined Republicans on rulings that let candidates raise unlimited amounts of money for ballot measure committees and allow super PACs and outside groups collaborate with candidates on door-to-door canvassing operations.

Joint fundraising committees, increasingly common, can be used to accept a large donation—for example, up to $929,600 for the Harris Victory Fund, and up to $844,600 for the Trump 47 Committee, two of the top-raising JFCs this cycle—that gets allocated between participating committees. The Harris Victory Fund and Trump 47 JFCs each split funds with dozens of state Democratic and Republican parties.