He was the Attorney for the Damned, the Great Defender, the champion of free thought who skewered biblical literalism at the Scopes Monkey Trial and the master courtroom rhetorician whose three-day oration spared two infamous young murderers from hanging. He was the terror of corporations and the battling friend of labor.

The most famous trial lawyer of his time, Clarence Darrow inspired reverential biographies, stage plays and performances from some of the 20th century’s greatest actors. For generations of attorneys, he has personified courage against long odds and the high-minded practice of law in service of social good. Defense attorneys still study his speeches like scripture.

But the Chicago attorney’s biggest cases were more than a decade ahead of him when he arrived in Los Angeles in 1911 to handle the highest-profile criminal case in the country. He narrowly escaped with his career — and his freedom — from what he came to call The City of the Dreadful Night. Whether he deserved to avoid prison is not totally clear.

Darrow was in town to represent the McNamara brothers, union men accused of dynamiting the downtown building of the anti-union Los Angeles Times in October 1910 and killing 21 people. Labor leaders had pleaded with a reluctant Darrow to take the case. There was a pervasive conviction that the brothers had been framed as a scheme to smear the union cause.

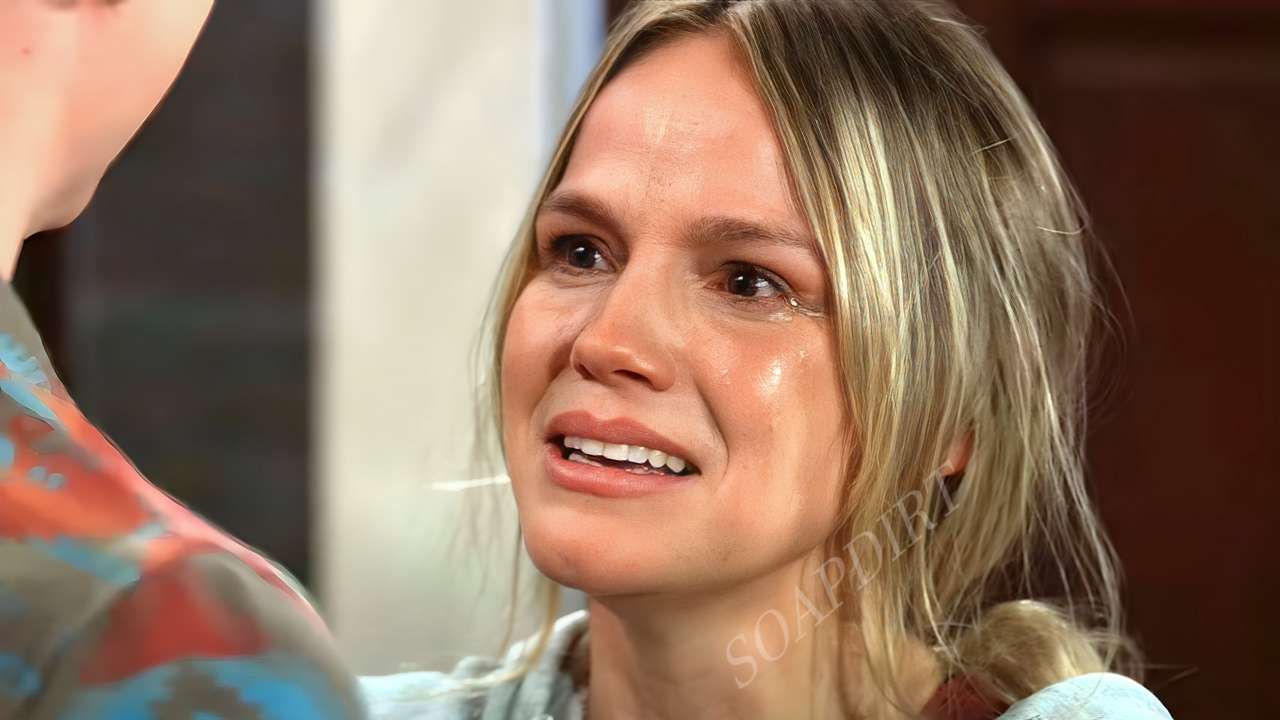

The famed criminal lawyer Clarence Darrow pleads his case to the jury in a 1913 trial.

(Los Angeles Times)

Darrow knew better. The evidence against his clients was overwhelming. He urged one McNamara brother to plead guilty to the Times murders, while the other would admit to a different bombing. Darrow settled the case, he would explain, to save his clients from hanging.

The trial for the so-called Crime of the Century never happened. Instead, it was Darrow himself who went on trial. The accusation: bribery. His chief jury investigator, Bert Franklin, had approached two prospective jurors in the McNamara case and offered them cash to vote for acquittals.

Just before the plea deals were finalized, detectives had caught Franklin trying to pass bribe money to juror George Lockwood, a retired Civil War veteran, on the corner of 3rd and Main streets. Darrow’s insistence that he had known nothing about it was undercut by his unexplained appearance on the scene at just that moment.

Now, Franklin was a key witness against Darrow. So was John Harrington, chief investigator for the McNamara defense team, who claimed Darrow had shown him a roll of $10,000 in cash — easily six figures in today’s dollars — meant for jury bribes. By Harrington’s account, when Franklin was caught, Darrow nervously blurted: “My God, if he speaks I am ruined.”

Darrow, in his mid-50s, seemed near despair during his three-month trial. “Glum and grim,” one reporter called him. “Mortified and resentful, heartbroken and trapped.” People fanned themselves in the courtroom’s stiflingly hot air. Lawyers expectorated into a spittoon. Thousands of spectators jostled for a look.

To represent him, Darrow picked the flamboyant and brilliant Earl Rogers, believed to be the inspiration for Perry Mason. Rogers cross-examined prosecution witnesses blisteringly, portraying them as scoundrels who were lying about Darrow to save themselves.

A 1932 photo of lawyer Clarence Darrow.

(Associated Press)

But there was also damning testimony from a detective named Sam Browne, who recalled Darrow’s words to him minutes after the abortive bribe attempt. “If I had known that this was going to happen this way,” Browne reported him saying, “I never would have allowed it to be done.”

The thrust of the defense: Darrow possessed no motive to bribe the jury, as he had already planned for the McNamara brothers to plead guilty. The trial pivoted on whether Darrow had finalized such a plan. (There was a good argument that the revelation of the bribery scheme had forced the brothers to plead, since it “revealed the desperation of the defense,” as the McNamara judge had remarked.)

In his summation to jurors, prosecutor Joseph Ford essentially blamed Darrow for the dynamiting of The Times. “It was the example of men like Darrow that caused the poor deluded wretch, J.B. McNamara, to believe that he could commit the crimes he did with safety to himself,” Ford said.

He invoked the pain of people who lost loved ones in the furnace of the burning Times building. He stretched his arms out toward Darrow and said, “Well and truly may the widowed mother turn to the defendant and say, ‘Give me back my boy.’ ”

When Darrow stood to make his own plea to jurors, he called Ford’s attack “cowardly and malicious in the extreme. It was not worthy of a man and it did not come from a man.”

Darrow’s remarks to jurors seemed to suggest that even if they believed him guilty, they should understand his motive had been to level the playing field for his underdog clients. He claimed the system was heavily skewed in favor of the prosecution. “They had the grand jury. We didn’t. They had the police force. We didn’t. They had organized government. We didn’t.”

Would the greatest legal advocate of his time be so stupid as to sanction such a ham-handed bribery scheme? “I am about as fitted for jury bribing as a Methodist preacher,” Darrow said. “If you 12 men think that I would pick out a place a block from my office — and send a man with money in his hand in broad daylight to go down on the street corner to pass four thousand dollars — why, find me guilty. I certainty belong in some state institution.”

Darrow insisted that he had been criminally charged because of what he stood for. “I am not on trial for having sought to bribe a man named Lockwood,” Darrow told jurors. “I am on trial because I have been a lover of the poor, a friend of the oppressed, because I have stood by labor for all these years, and have brought down upon my head the wrath of the criminal interests in this country. Whether guilty or innocent of the crime charged in the indictment, that is the reason I am here, and that is the reason that I have been pursued by as cruel a gang as ever followed a man.”

Darrow wept. Spectators wept. Jurors wept. Even one of the prosecutors called it “one of the most marvelous addresses ever delivered in any courtroom” but added, “It has mighty little to do with his guilt and innocence.”

Jurors deliberated less than 40 minutes before acquitting Darrow. But early the next year, he was on trial again, this time on the charge of attempting to bribe a second juror, a carpenter named Robert Bain. This time, he did not have the defense of lacking motive, since this attempt occurred well before settlement talks were in motion.

In March 1913, the jury deadlocked. Eight voted to convict. Four held out for acquittal. Los Angeles prosecutors dropped the case, and — two years after stepping off a train in L.A. — a chastened Darrow returned to Chicago.

“Everybody had had enough of Darrow and just wanted him to get on a train and get out of town,” said Nelson C. Johnson, author of the book “Darrow’s Nightmare: Los Angeles 1911-1913,” which is subtitled “The Forgotten Story of America’s Most Famous Trial Lawyer.”

Johnson, a retired New Jersey judge, read Irving Stone’s “Clarence Darrow for the Defense” as a young man and took inspiration from it as he pursued the law.

Asked why Darrow mattered to him, Johnson replied, “Courage of conviction. You’re gonna make me emotional.” He added, “Standing by your client when the shit hits the fan and you know the prospects are pretty ugly and you also know at the end of the day you may not be getting paid. Once you start representing a client, that’s a sacred trust. That person is putting their life in your hands, and they’re saying, ‘Please help me.’ Every now and then you have a client, you’re their only friend.”

This is how many lawyers talk about Clarence Darrow, even now. It makes them emotional.

Nelson’s conclusion: Darrow “probably wasn’t guilty.” The four jurors who sided with him in the second case saved him from historic obscurity.

“If he was convicted, you and I would not be talking about him, and I would not have written that book,” Johnson said. “Once you’re a convicted felon, you’re not going to become a lawyer in any state, even in those days.”

Darrow’s most celebrated cases came after Los Angeles. He was in his late 60s in 1924 when he represented Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb, two Chicago teenagers who killed a 14-year-old boy to demonstrate their ability to carry out the perfect crime. He persuaded a judge to spare their lives.

The following year, he defended a Tennessee schoolteacher named John Scopes who was accused of teaching evolution. The duel between the agnostic Darrow and the biblical literalist William Jennings Bryan inspired the play “Inherit the Wind.” The year after that, Darrow won an acquittal for a Black man charged with firing into a white mob as it surrounded his brother’s home in Detroit.

Geoffrey Cowan, a USC law professor, held Darrow in such high esteem that he helped launch the Clarence Darrow Foundation to fund public interest law. But while researching his 1993 book “The People v. Clarence Darrow: The Bribery Trial of America’s Greatest Lawyer,” Cowan concluded that the evidence against Darrow in the jury-bribery scheme was strong.

“I totally believed in Darrow, and I went into this convinced that Darrow was innocent,” Cowan told The Times. “I thought the fun thing to do would be, I could spend some time digging into why he was framed. That was my premise, but as I began to investigate, I became convinced that he was guilty.”

A good number of Darrow’s friends and confidantes had no trouble believing he was behind the bribes. Even Lincoln Steffens, the celebrated muckraker who testified on his behalf at trial, wrote in a private letter: “What do I care if he is guilty as Hell.”

Cowan said he struggled with whether he was justified in accusing Darrow without being totally sure. “I concluded that the standard for the writer could be more like a civil standard of ‘more likely than not,’ ” he said. “I wanted him to be a hero. But he was flawed. If you’re trying to be empathetic and say, ‘OK, what was he feeling?’ I think he thought [the McNamaras] weren’t going to get a fair shake, that everything was stacked against them.”

Los Angeles was a boom town in the early 1910s and a war zone between the forces of labor and capital.

“We don’t tend now to picture Los Angeles as the Wild West,” Cowan said. That did not justify jury tampering, but “there were very brutal fights. There was a roughness about things.”

Sources include “Darrow’s Nightmare: Los Angeles 1911-1913” by Nelson C. Johnson, “The People v. Clarence Darrow: The Bribery Trial of America’s Greatest Lawyer” by Geoffrey Cowan, and “Clarence Darrow: A One-Man Play” by David Rintels, based on Irving Stone’s “Clarence Darrow for the Defense.”