Sixty-five years after slavery, the Jewish management of the New York Times deigned to elevate Blacks to a level of esteem it had long afforded to others. Up until March 7, 1930, the Times refused to capitalize the word Negro, but from that day forward, the paper pompously reported, it would be giving “tribute to millions who have risen from a low estate into ‘the brotherhood of the races.’”

It is not merely a typographical change; it is an act in recognition of racial self-respect for those who have been for generations in “the lower case.”

Despite its insufferable pretentiousness, the New York Times was in fact admitting that Blacks had been treated as less than citizens by its Jewish owners in all the previous years. By contrast, most of the leading Southern newspapers had capitalized “Negro” long before the northern Times, as had the grand wizard and founder of the Ku Klux Klan, William J. Simmons, who had been capitalizing Negro in his published writings a decade earlier.

The New York Times was in print for forty-five years before it was acquired by the Tennessee-born Jew Adolph Ochs (pronounced ox; b.1858–d.1935) in August of 1896 for $75,000 ($2.8 million in today’s value), which he obtained from the Rothschilds’ American representative August Belmont, investment banker Jacob Schiff of Kuhn, Loeb, and Macy’s department store owner Isidor Straus. He increased the paper’s circulation of 9,000 to nearly 80,000 in just three years. It continued to grow under Ochs’s management, and ultimately it was deemed the American “newspaper of record,” meaning that it is presumed to set the standard of journalism for the nation and that its articles establish a definitive record of current events for use by future scholars and historians.

Largely because of its Jewish family management and New York base, the Times has developed a reputation as the bastion of American liberalism particularly around racial issues, but in fact its actual historical role as a fomenter of racial hatred is a far more accurate description. Since the Jewish acquisition of the Times in 1896, the paper’s editorial slant had been consistently white supremacist and thoroughly hostile to Black people.

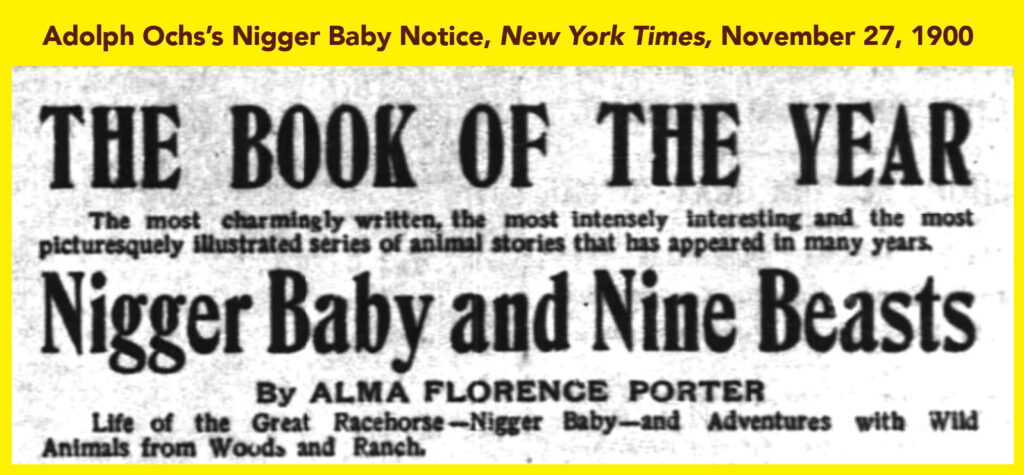

It is not as though Ochs was unaware of the power he had in the pre-radio and -television era to create lasting images of any person or group of people. He was an executive board member of the Anti-Defamation League in its earliest years, and according to the ADL’s own timeline, he wrote to newspaper editors nationwide “discouraging the use of ‘objectionable and vulgar’ references to Jews in the media.” By 1920, the ADL reported, “the practice had virtually stopped.”

Thus, Adolph Ochs was good for Jews, not so good for Blacks. He married the daughter of Rabbi Isaac M. Wise (b.1819–d.1900), the father of Reform Judaism in America, the branch of Judaism practiced by most Jews today. Unfortunately for Blacks, Rabbi Wise’s racial ideology was purely Southern, staunchly pro-slavery, and boldly white supremacist. He believed Blacks to be subhuman “mongrels,” and as publisher of The Israelite, “the world’s largest Jewish newspaper,” he detested the abolitionists, calling them “demons of hatred and destruction” who “know of no limits to their fanaticism.” After all, he believed, “We are not prepared, nobody is, to maintain it is absolutely unjust to purchase savages, or rather their labor…” Of the native Americans the rabbi taught they “are very primitive and ignorant….[They do] nothing besides loafing and begging.” As the founder of the nation’s only Jewish seminary, Wise trained America’s rabbis into his ideals—freely imparting and further ingraining the long-standing racial hatreds he shared with his son-in-law Adolph Ochs. Indisputably, these two giants of Judaism had a profound effect on the racial consciousness of America.

At the tender age of 19, Ochs purchased the Chattanooga Times in Tennessee, where he reveled in the opportunity to advance his white supremacist convictions. And that’s not hyperbole—that is Ochs’s stated objective. In one 1888 commentary he wrote of “the necessity of white supremacy—we should rather say, the supremacy of intelligence and morality—in the South, if we would have order, law, civilization.”

Two years later Ochs published a special 28-page Confederate Reunion Souvenir Edition of his newspaper, which honored the “struggle” of the “slave states,” memorializing the words of Confederate icons Pres. Jefferson Davis, Gen. Robert E. Lee, Vice Pres. and Secretary of War Judah P. Benjamin, and “that military genius, wizard of the saddle” Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest—the terrorist mastermind of the Ku Klux Klan. As Ochs memorialized, “There was no braver and therefore more chivalrous soldier of the late war than Nathan Bedford Forrest.” Under the Jewish Ochs the Chattanooga Times proved that any publicity organ of the Ku Klux Klan would only be redundant.

The rest of the special Confederate edition was spent in glowing tribute to the noble personages that imposed war on a nation in the name of chattel slavery, including a full page with the portraits of all 96 Confederate army generals. Ochs’s white/Jewish supremacist ideology made an effortless transition from Chattanooga to New York when he bought the Times in 1896, as is easily demonstrated by these two literary items from the Ochs newspaper archives:

Ochs in the Chattanooga Times, 1879:

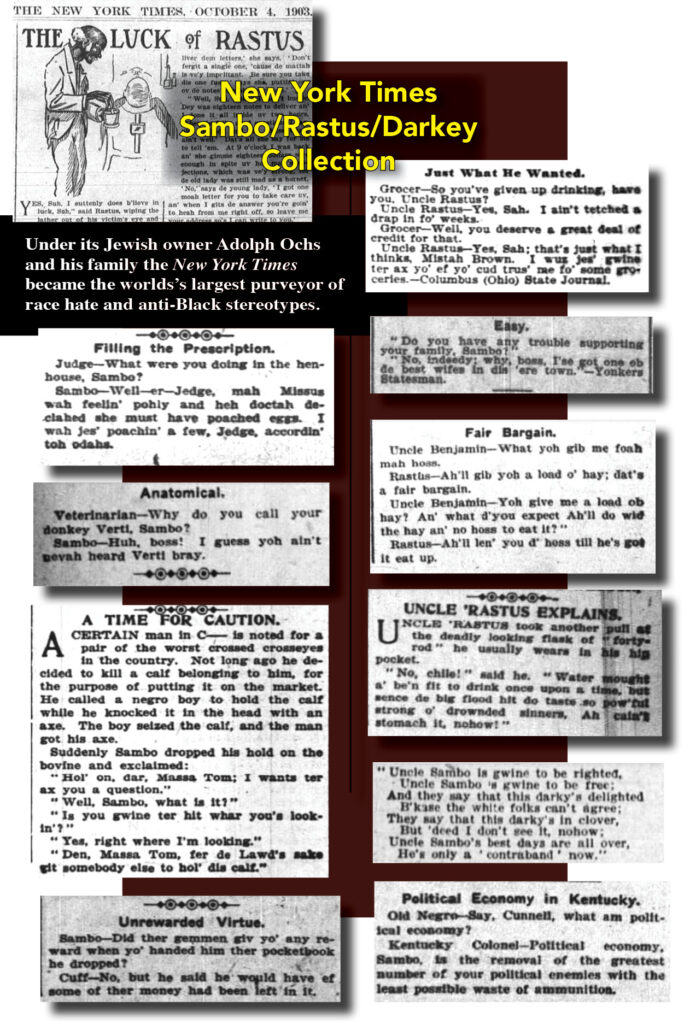

“Sambo, what am de difference ‘tween a baseball player and you’self?” “Gib um up, Mose.” “Case catches a foul on the fly when it’s light, an’ de udder steals ’em off de roost at night.”

Ochs in the New York Times, 1904:

“Sambo—Did ther gemmen giv yo’ any reward when yo’ handed him ther pocketbook he dropped? Cuff—No, but he said he would have ef some of ther money had been left in it.”

Even with his pick of great turn-of-the-century thought leaders speaking intelligently for the Black masses like W.E.B. DuBois, Booker T. Washington, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, T. Thomas Fortune, James Weldon Johnson, Mary McLeod Bethune and William Monroe Trotter, Ochs ensured that the white and Jewish readers he catered to got their daily fill of chicken-stealing, bad-smelling coons, mammies, darkeys, and sambos—all terms his newspapers regularly applied to Blacks. As Dr. Steven Bloom wrote in a fit of understatement, “Ochs possessed many Southern prejudices against the Negro which were often evident in Times editorials.”

Into the 1950s—under Ochs’s son-in-law Arthur Hays Sulzberger—the Times was consciously managing the Black image for all the world to see. Photographs of Blacks were “carefully chosen to avoid any suggestion of social integration.” Black wedding photos were barred into the 1950s and only appeared later when the bride and groom were light-skinned.

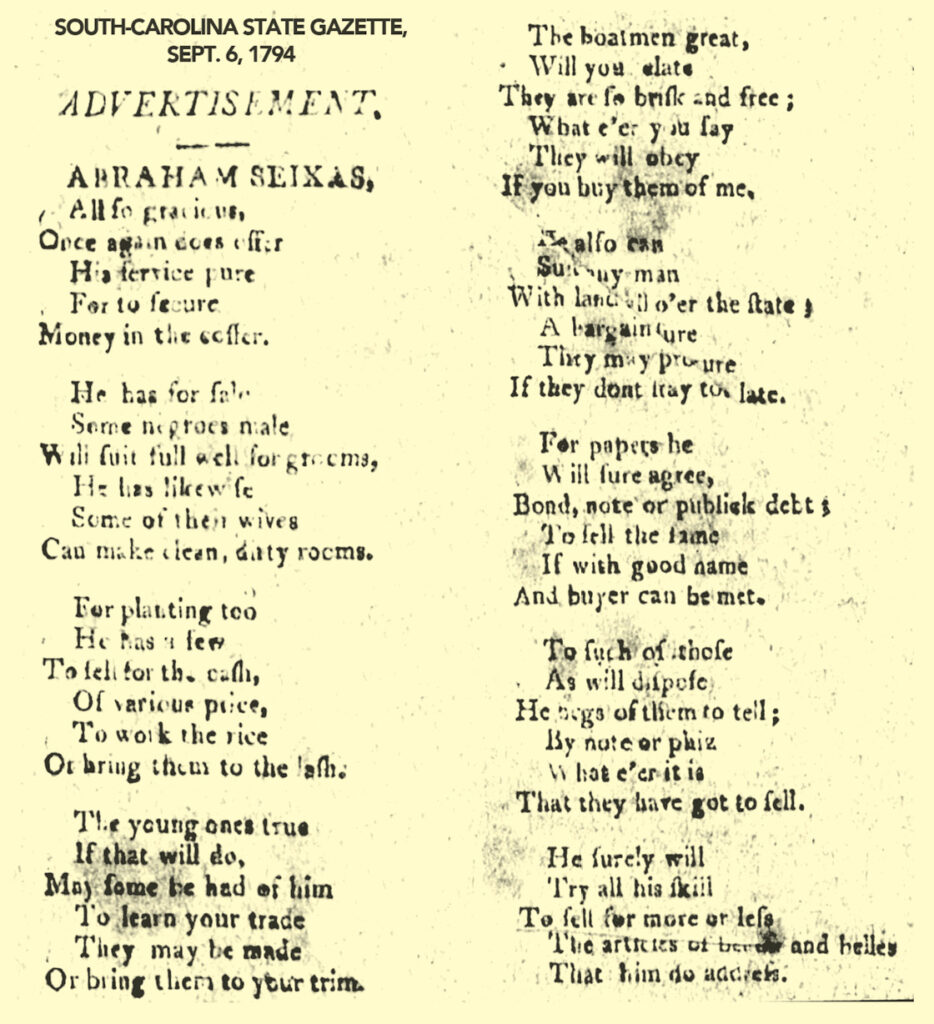

After all, the Sulzbergers were proudly descended from the Seixas family, one of the major Jewish slave-owning clans in American history. Abraham Seixas advertised openly for his slave-trading business in South Carolina, enticing customers with discounts: “will not charge for ‘sucking children of negroes’ (infants).” Foreshadowing the Sulzbergers’ literary bent, Seixas’s 1794 slave-trading ad highlights his affinity for both rhyme and racial evil:

ABRAHAM SEIXAS,All so gracious,

Once again does offer

His service pure

For to secure

Money in the coffer.He has for sale

Some negroes male,

Will suit full well for grooms.

He has likewise

Some of their wives

Can make clean, dirty rooms.For planting too, He has a few

To sell for the cash,

Of various price,

To work the rice

Or bring them to the lash…

Shaping the Racial Mind of America

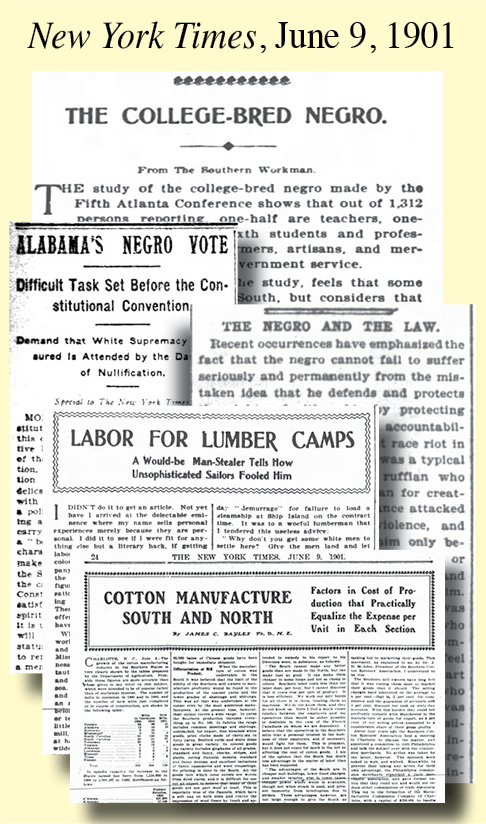

The racist thrust of Ochs’s New York Times is best exemplified in the Sunday edition he published on June 9, 1901. Five separate articles from this alleged bastion of liberalism contain ideas, beliefs, and attitudes indistinguishable from those of the Ku Klux Klan, and one even approvingly recounts the Tennessee origins of the terrorist group. According to the Times, they were just some “fellows…discussing ways and means of having a livelier time [when] someone suggested a club or society.” Yes, he means the KKK.

“At that time the celebrated Parson Brownlow was ruler in Tennessee, and the negroes and certain evil white men held the country in terror, burning houses, killing ex-Confederates, and insulting women. When it was observed what terror the members of the Ku Klux (a deliberate corruption of the Greek word Kuklos, a circle,) inspired in the negroes, the social club gradually transformed itself into a band of regulators.”

In that same 1901 edition which berated that “irresponsible piece of black humanity”—the “negro lumberjacks”—the Times writer advocated the physical beating of Blacks in order to “drive the men to work,” because “The nearer you come to the old slavery methods, the nearer you come to getting the negro to work…” The article continued:

So you will see a slim white lad take a piece of stick, march into the quarters, and proceed to drive the men to work with a few blows. Occasionally a man gets killed for doing this, or whipped, but usually the negro goes resignedly and sadly, like a cow, while an occasional whack urges him on. When a negro steals anything out of a store, two to one they do not arrest him. They put a revolver to his head, march him out into a back room, tell him to lie over a barrel, and then spank him with a strap….Northerners cannot realize how low in intelligence, how irresponsible the pure negro is. He is an animal…even worse than most animals…

In the same issue the Times decried the attitude of Blacks who are “too indolent and improvident” to appreciate the “opportunities” in cotton picking. “Unfortunately, the negro is degenerating….Were he differently constituted…he would be infinitely more dangerous than he now has the energy to be.”

Yet another June 9, 1901, article decried “the college-bred negro” and attacked the NAACP’s only Black official, W.E.B. Du Bois, who advocated higher education for the “talented tenth” of his people. The Times repudiated the notion and insisted that all Blacks would be better off “cooking, sewing, and [in] agriculture.” The front page of that same issue expressed the drawbacks of allowing Alabama Blacks to vote, and worried that the Black voters were “a mass of ignorant and mercenary negroes who cannot be trusted with the privileges of full citizenship” and who were “a menace to the supremacy of the white citizen [and] to the well-being and prosperity of the State.” The writer then schemes about “how to take away from the negro the voting privilege without depriving any white man of the ballot.”

In 1903, Ochs’s Times complained bitterly:

There are in New York thousands of utterly worthless negro desperadoes, gamblers when they have money and thieves when they have none, moral lepers and more dangerous than wild animals…who easily and almost naturally develop into burglars, highwaymen, and murderers.

The Times asserted that a “negro judge” of South Carolina “was a typical African, and his grotesque appearance was not unlike that of an ordinary ape” and that the attorneys in his court addressed him as “Sambo.”

In his September 12, 1912, edition, Ochs differentiated between good and bad “redskins” and declared: “They are the nobler red men, without the bloodthirstiness of their sires and their capacity for rum and mischief. They have passed through the critical period of contact with the white races, and have emerged into the full light of civilization.” Ochs adds, “Racial prejudice has never been manifested against the American Indian.”

Yes. That is the New York Times—the Jewish-owned New York Times. And yet there is more.

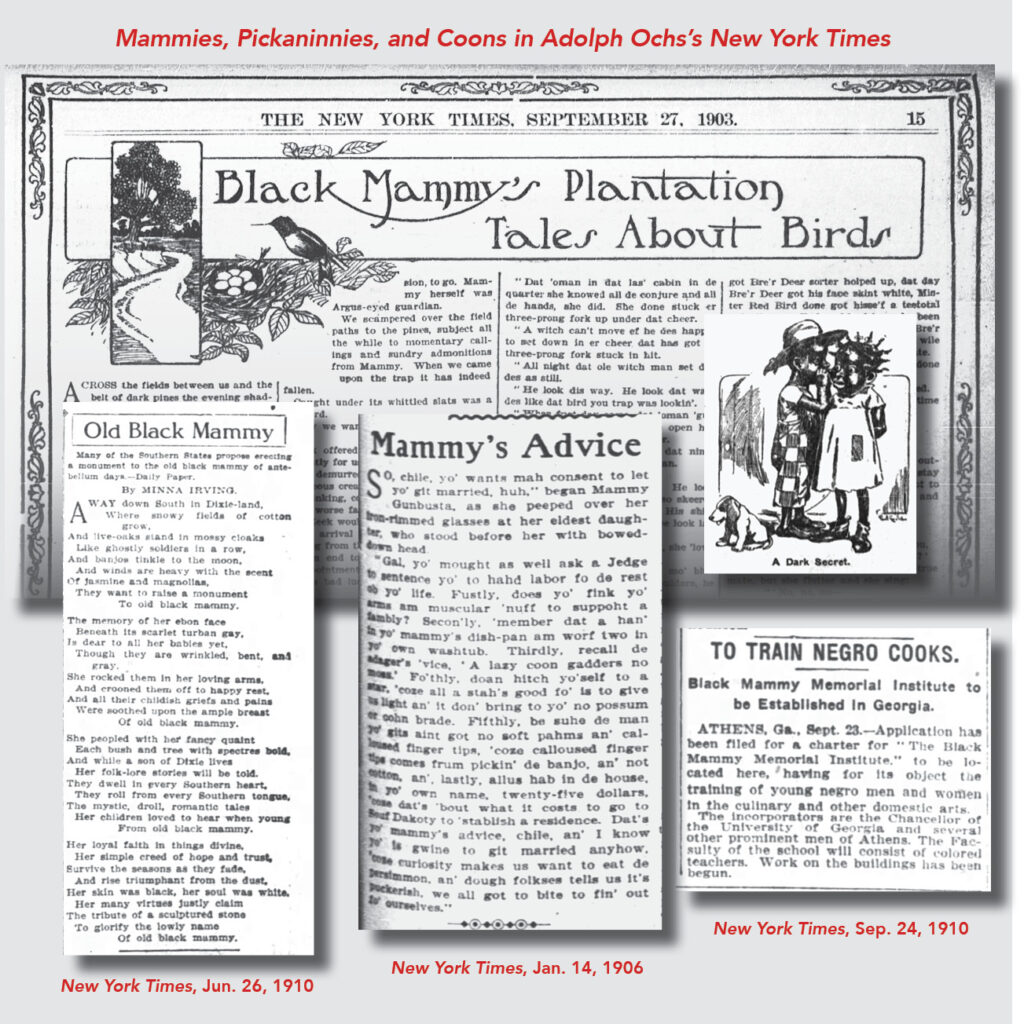

Mammies, Coons, & Pickaninnies

If there is any liberalism at all to be found at the Times, it was its liberal usage of racial invective throughout its dailies. Terms like nigger, coon, darky (also darkey), buck negro, sambo, cuff & rastus, mammy, pickaninny (“colored child”), blackface, chink, redskin, slant-eyed, Jap, chinaman and other racist terms appeared hundreds of times, helping to inflect perspective into Ochs’s editorial offerings. In 1908, just a year before the founding of the NAACP, Ochs had a promising employment opportunity for Black women:

There is no reason why the South should be deprived of its Old Mammies. There is plenty of raw material in all conscience. A bandanna handkerchief, a calico frock, an apron, a suggestion of embonpoint, and a course of lessons in Southern cookery, which is now understood only in the North, will transform any intelligent colored woman into an Old Mammy. Northern capital could not be better employed, and the firmer establishment of friendly relations with the South would be secured by the operation. Why not have Old Mammy training schools at once?

After all, Ochs’s daughter Iphigene Sulzberger insisted, “We love the negroes….We must look after them but keep them in their place; they are fine as long as they stay in the kitchen.”

Indeed, the “Old Black Mammy” was a popular theme in the pages of the Jewish paper—the term appears 646 times—including this moving ode to Black womanhood:

She rocked them in her loving arms,

And crooned them off to happy rest,

And all their childish griefs and pains

Were soothed upon the ample breast of old black mammy.

One 1903 Times issue devoted a full page to “Black Mammy’s Plantation Tales about Birds” (as if Ochs needed to distinguish from “white mammies”?), complete with an illustration of two “pickaninnies.” In a 1906 article titled “Mammy’s Advice” Ochs openly mocked Blacks with a minstrel rendition of what he believed to be “colored” dialect (note: the misspellings are intended to convey the image of Black illiteracy):

“So chile, yo’ wants mah consent to let yo’ git married, huh,” began Mammy Gunbusta, as she peeped over her tron-rimmed glasses at her eldest daughter, who stood before her with bowed-down head.“Gal, yo’ mought as well ask a Jedge to sentence yo’ to hahd labor fo de rest of yo’ life. Fustly, does yo’ fink yo’ arms am muscular ’nuff to suppoht a fambly? Secon’ly, ‘member dat a han’ in yo’ mammy’s dish-pan am worf two in yo’ own washtub. Thirdly, recall de adager’s ‘vice, ‘A lazy coon gadders no moss.’ ….”

And on and on.

Ochs’s ongoing obsession with Ol’ Mammy again surfaced in 1912 when he reported that “Housewives in Georgia Plan to Dismiss the Negroes” and replace them “by importing white women from countries in Europe to take the place of the lazy and unsatisfactory negroes….The negroes are unfit or unwilling to work on the farms, while their women are equal failures in the homes.” Ochs’s insult was quickly assailed by the Black-owned New York Age, which monitored the daily racial damage Ochs inflicted on the world:

“We find a few white people throughout this country who have yet to learn that many Negro women find it more profitable and congenial to keep house for themselves than to work for some white family, and there are thousands of Negro farmers who have long since learned that it is more profitable to cultivate their own farms than to cultivate a farm for a white man. The sooner the white man in the South can realize that every Negro woman and Negro man was not born to be a servant for some white person, the sooner will conditions adjust themselves to the benefit of both races.”

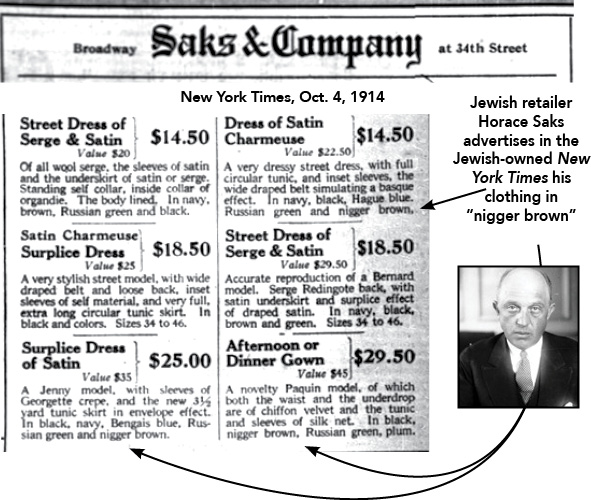

It may surprise many to know that even before Adolph Ochs acquired the paper, Jews freely advertised in the New York Times in a racially discriminatory manner, seeking help and accommodations with the phrase “Jews preferred.” Ochs continued the practice in his classified ads section, where readers could find “colored” maids, cooks, and laundresses. And if the Times readers offered employment opportunities, the Jewish-owned newspaper was fine with the catchphrase “colored need not apply.”

The truly endless expressions of the New York Times’s white Jewish supremacy were bordered by prominent advertisements by firms with Jewish surnames like Simonson, Haas, Koch, Altman, Siegel, Arnheim, Stern, Fischer, Weber, Sidenberg, Wissner, Abraham & Straus, Krause, Millekin, and Miller—none of whom were known to offer any objection or protest. The well-known Jewish retailer Saks & Company was advertising “new fall skirts for women,” assuring potential customers that if they didn’t want blue stripes, black, or navy, they also had skirts in “nigger brown.”

NAACP versus the Jewish New York Times

Jews have insisted that they were stalwart supporters of the civil rights movement, which they say began with Jewish investment of time and resources in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Yet the world’s strongest Jewish megaphone for Jewish interests did not even mention the formation of the organization until 1911, two years after its founding. The Times matter-of-factly monitored the new organization’s activities and finally in 1912 the Jewish editors took a stand—against Black civil rights!

A New York court ruled in 1912 that Harry A. Levy, the Jewish owner of the Lyric Theater in New York, racially discriminated against Louis Baldwin and “a negress” when he had them removed from their seats in the orchestra section. Chicago’s Broad Ax lauded the landmark ruling, calling it “one of the most important decisions ever rendered [respecting] the civil rights of the colored citizens of New York,” the first conviction under the anti-discrimination law. The Pittsburgh Courier headlined, “Victory for Whole Race,” but Ochs’s Times was outraged:

“The case was brought by the local Vigilance Committee of the National Association for the Advancement of the Colored People. Probably the theatrical managers would admit negroes to orchestra seats as readily as white persons, if it were found profitable. It is a matter of business with them, not of prejudice. But, if compelled to admit negroes, they would find that the prejudice of white patrons deprived them of their profits. This would amount to confiscation, and an invasion of the rights of private business….The friends of the negroes [NAACP] are doing them a disservice in this matter. [NYT, Feb. 1, 1912]”

Significantly, Ochs’s subtle transfer of victimhood from Blacks to Jewish business owners who enforce openly racist Jim Crow policies is a common rationale used by Jews to justify their own racism—even claiming themselves to be victims of a “greater” racism by gentile whites. Further, Ochs’s disdain is directed not at those supposed racist gentiles but at the “friends of the negroes”—the NAACP.

Somehow, the fact that the first significant civil rights case brought by the NAACP was about the racist practices of a Jewish business has been buried in history. It certainly qualifies as a major case because Levy’s theater was managed by the Jewish-owned Shubert chain of 150 theaters.

The editorial writer for the Age wrote: “And such names as Adolph S. Ochs and B.C. Franck which adorn the upper left hand corner of the editorial page, believe it their duty to preach race hatred in the United States and in the same breath demand that another nation [Russia] treat a certain element of its citizens with a more broadminded spirit tempered with justice.” As Dr. Bloom lamented, “And again this Jewish-owned newspaper seemed to be concerned only with Jewish rights and often at Negro expense.”

The “Yellow Peril”: The Times’s War on Asians

After the Civil War immigration from all over the globe increased exponentially. As foreigners poured in by the millions seeking new homes and better lives, the New York Times led in the racist effort to ban that segment of humanity coming from Asia. The so-called Chinese Exclusion campaigns of the late 1800s under the fear-mongering banner of “Yellow Peril” reached a fever pitch in white America. The term “Yellow Peril” appears in the Times at least 374 times and begins in 1896 in the very month that Ochs took control. A 1904 letter he published warned:

“It is easily conceivable that a couple of generations will suffice for the slant-eyed peoples to present a united and unbroken front to the Caucasian. A little longer and India could easily see where her interests lay. Japan is the nucleus of all this, and the necessity of defense against white aggression is the cohesive force which must ultimately bind them together.”

In fact, the Asian exclusion effort was spearheaded by Julius Kahn, the Jewish congressman of San Francisco who advanced a bill in 1902 to deny all Asians entry into the United States for 20 years! So central was Kahn to the Nazi-like edict that the legislation bore his name—the Kahn Exclusion Act, which he explained was necessary because the Chinese people were “morally, the most debased people on the face of the earth.” Adolph Ochs’s Times added its voice to the effort, encouraging the crafting of the law to promote “cheap Chinese labor” that would help the South replace the “thriftless and improvident negro,” who “has been found unequal to the opportunities open to him” (read: cotton picking). Ochs had no love for the Asian but saw them as he saw all non-whites—as necessary labor in specifically designated servile roles.

Another powerful Jewish leader—American Federation of Labor head Samuel Gompers—joined in this racist campaign. He and B’nai B’rith leader Herman Gutstadt believed violently that Asian immigrants threatened white labor, and in 1901 they co-penned one of the most racist documents in American history, in which they presented the choice facing white America in its very title: MEAT vs. RICE: AMERICAN MANHOOD AGAINST ASIATIC COOLIEISM; WHICH SHALL SURVIVE?

So treacherous was this screed, so blatant its appeal to deep racial hatreds, so transparent in its intent to incite racist violence, that it would easily surpass in its cruelty the worst propaganda of Hitler’s Nazi party. Among its most vile offerings about the Asians was that

they have no standard of morals by which a Caucasian may judge them….The Chinese are like a sponge; they absorb and give nothing in return but bad odors and worse morals….[W]hen the Chinese servant leaves employment in an American household he joyfully hastens back to his slum and his burrow, to the grateful luxury of his normal surroundings—vice, filth and an atmosphere of horror.

Not to worry. Herman Gutstadt’s son Richard E. Gutstadt, well trained in his dad’s ethics, became the national director of the Jewish supremacist Anti-Defamation League in 1931 until 1948.

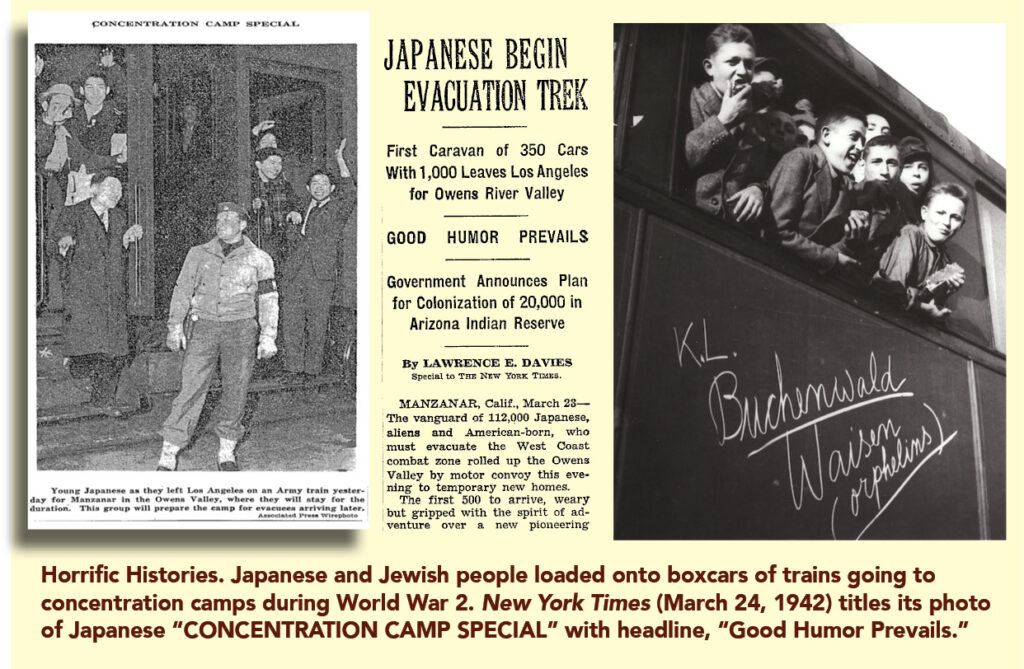

The Times’s Concentration Camp Cover-up

When in February of 1942 Pres. Theodore Roosevelt issued his infamous Executive Order #9066 forcing Japanese Americans into concentration camps, the Sulzberger-run New York Times was the model of racial hypocrisy. By 1942 Adolf Hitler had constructed hundreds of concentration camps for Jews and other enemies of the Nazi state. Yet Sulzberger’s New York Times saw no parallel in what America was simultaneously doing to Japanese Americans—using precisely the same rationale.

In its March 24, 1942, issue, the Times displayed a photo of Japanese prisoners in boxcars, under the header “CONCENTRATION CAMP SPECIAL.” The photo is nearly identical to the photos of Jews being forced into boxcars heading for Nazi concentration camps, but the Sulzberger family saw the Japanese experience as entirely the opposite. The Sulzbergers’ headline:

JAPANESE BEGIN EVACUATION TREK…GOOD HUMOR PREVAILS

You read that correctly. And the Jewish paper continues, claiming the Japanese-American prisoners were “weary but gripped with the spirit of adventure over a new pioneering chapter in American history.” Then this bizarre Times description of the internment of the Japanese: “…assembling long before daylight near the Pasadena Rose Bowl, scene of many a great football game.” Their destination was “a new reception center rising as if by magic at the foot of snow-capped peaks.”

Clearly, the Sulzbergers believed their role was to sanitize rather than report on one of the most despicable chapters in American racial history. There is little doubt that Times writer Lawrence E. Davies invented the “quotes” he says came from two Japanese men who had just been ripped from their homes and livelihoods: “This is a wonderful place. We didn’t expect such fine treatment.” Another forced internee allegedly says, “I’m going up there to do any job they put me on in the meantime.” Of the Japanese Davies adds the improbable: “conversations on every side emphasized the adventurous nature of the evacuation movement.” For context, ask if Auschwitz could ever be likened to an Airbnb.

The RACE WARS of the New York Times

The epidemic of Black lynchings reached into the thousands in America, but the Jewish-owned newspaper was coldly matter-of-fact, showing little trace of indignation or even displeasure at the countrywide carnage. To the Times, these white lynchers of thousands of innocent Blacks were not savage criminals but inventive dispensers of justice driven to the act by “black depravity.” And though there was never a trial, indictment, or even a legitimate arrest, the Black victims were most often presumed guilty. For example, a 1900 Ochs headline declared that a Negro Murders A Citizen and in the subtitle almost gleefully forecasted his fate: “Posses Are Looking For Him, and He Will Be Lynched.” The paper similarly forecasted that “the negro probably will be hanging to a tree before morning,” in “A Lynching Expected.” Another Times article “objectively” reported a burning at the stake in Alabama, opining that the “negro” victim “certainly has been punished for his crime.” The “reporter” added judiciously that “his identity was thoroughly established by his victim.”

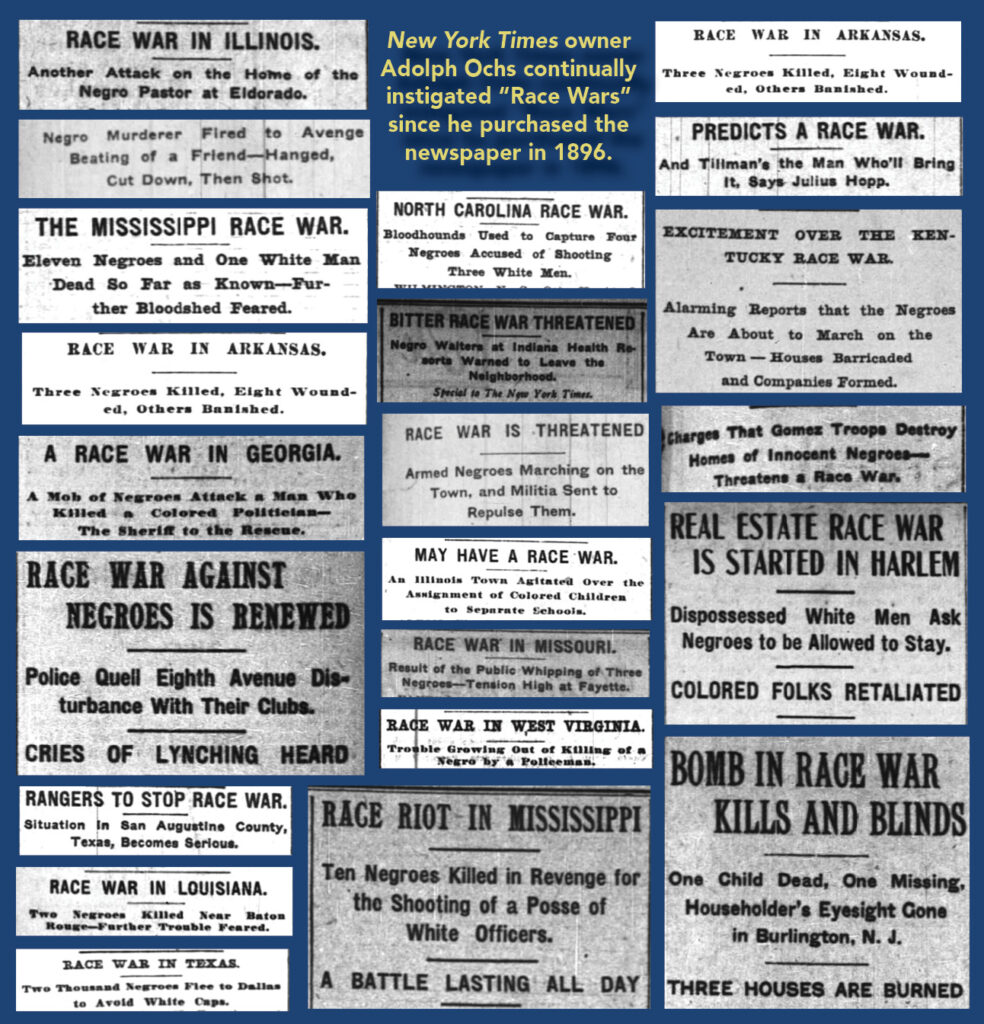

The Times demonstrated its propensity to declare “race wars,” as the term is repeated across many editions at least 390 times—as in these headlines:

Race War Threatened

Race War Imminent

May Have a Race War

Girls Precipitate Race War

Predicts a Race War

Arson Follows Race War

In these actual headlines Ochs appears to want to instigate racial violence on a state-by-state basis:

The Mississippi Race War

Race War in Missouri

Race War in West Virginia

Race War in Arkansas

A Race War in Georgia

Georgians Fear Race War

Race War in Texas

Race War in Louisiana

North Carolina Race War

Excitement Over the Kentucky Race War

In Ochs’s Florida “race war” of 1897, the Jewish-run paper covered it this way:

RACE WAR THREATENED: B. Pendleton arose and in a voice hoarse with passion shouted: Are there enough whites in this building to aid me in lynching this negro brute? The effect was electrical. Pistols were drawn and shouts of Let’s lynch him! Our women must be protected! Yes, We will stand by you! filled the room.

The lynching of one Black man was justified by the claim—fully accepted by the Times reporter—that “the negro” had struck a white woman on the head and then “roasted” her baby over an open fire. The headline of one article was Score Of Negroes Killed By Whites, subtitled “Trouble Started Over Non-Payment of a Negro’s Note…” The first sentence: “As the result of a race war…eighteen negroes are known to be dead…” The Times felt this alleged “non-payment” would adequately account for one of the most depraved racial massacres in American history. It added, “[A] negro grew insulting and trouble followed.” Thus, for Ochs the flimsiest of pretexts justifies the bloodbath.

Similarly, when a Black political leader was beaten to death and then shot, the Times headline was Negro Uprising Feared, showing concern for the safety of whites and none over the barbaric lynching of the Black man. In another, the Times simply accepted the word of a 14-year-old girl that she was “attacked,” and reported that “About 300 shots were fired into the negro’s body,” before the corpse was dragged through town and displayed “in the colored settlement.” The Times did not question that another lynch mob relied solely and totally on the word of a five year old. A 1909 Florida lynching was mentioned in the Times in a one-column-inch description, the last two sentences of which read: “Twenty shots were fired into his body. The negro confessed.”

Prior to Jewish ownership, the Times, though firmly representing white supremacy in its coverage of anti-Black violence, at least exhibited a concern over the wholesale trampling of due process in these common American horrors. The pre-Ochs Times carried speeches and accounts condemning the lawlessness of the lynchers and its headlines would often scream of outrage, using the appropriate terms for the lynching like “massacre,” “butchery,” “slaughter,” “atrocity,” and “terror,” and even referring to the perpetrators of lynching as “barbarians,” “savages,” and “fiends.” After its purchase by Adolph Ochs, the paper shifted its coverage to simply regurgitating the white Southern/Jewish supremacist perspective.

Adolph Ochs’s Ku Klux Klan

In 1902 and 1905 respectively, the Times reviewed Thomas Dixon’s violent race-baiting novels The Leopard’s Spots and The Clansman. Dixon expounded freely on how the “liberties” of northern Blacks were the cause of Southern white violence and lynchings; a generation before Hitler, the Times openly and approvingly quoted Dixon’s views on the supremacy of the “Aryan race.”

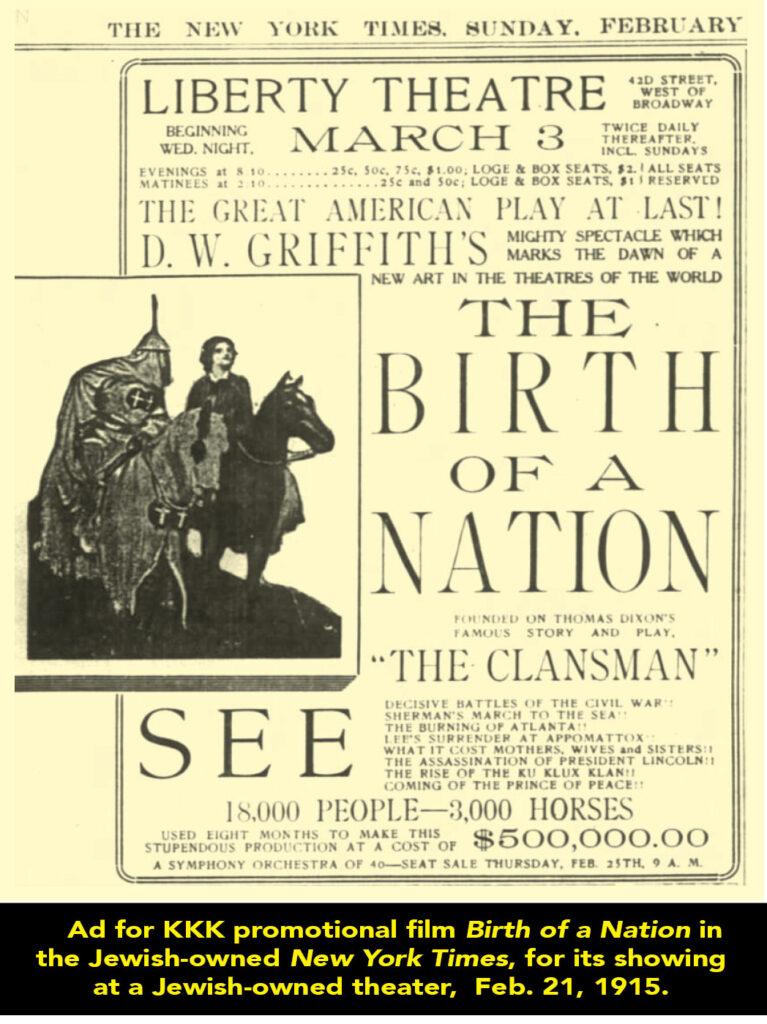

The books were turned into a silent movie extravaganza in 1914 by a group of Jewish financiers from Massachusetts and titled The Birth of a Nation—a movie so racially atrocious that its showing around America actually fueled the revival of the long-defunct Ku Klux Klan. For decades hence the film became the most effective recruitment tool the KKK ever had. One of the film’s main distributors was none other than the Jewish soon-to-be movie mogul Louis B. Mayer, who used its profits to start the legendary Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studio. Ochs’s Times extolled Birth of a Nation as “spectacular” and “impressive,” and advertised its showing when it played 750 times at the Jewish-owned Liberty Theater in New York. The Times said the KKK was not a terrorist cell but “a company of avenging spectral crusaders sweeping along the moonlit roads.”

When the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill of 1922 came to their attention, a bill American Blacks so passionately advocated, the Times editors printed a letter from a reader that one must presume gave a good account of Ochs’s sentiments on the matter:

“All the negro votes and Dyer bills from now till doomsday cannot prevent men avenging crimes against their mothers, wives and sisters. The negro is not blessed with the inhibitions of the passions that white men have gained by centuries of self-control.”

Black “Rape” and White Slavery

At the same time that the rates of Black lynchings were at their highest and the cry of “rape” was at its loudest, Jews themselves were heavily engaged in the international “white slavery” trade, where in many urban centers around the world Jewish pimps made commerce of Jewish and Gentile women and girls in that brutal rape-for-profit business. According to University of Tel Aviv scholar Robert Rockaway,

Starting in the 1870s, Jews played an increasingly conspicuous role in commercial prostitution. By the twentieth century, Yiddish-speaking Jews dominated the international white slavery traffic, especially in Jewish women, out of Eastern Europe…

The New York Times under Adolph Ochs became the most potent media vehicle by which the “negro rape” canard was spread throughout the world. In no small way was the myth fueled by the Times’s 1914–1915 coverage of the notorious Leo Frank case, in which the Jewish B’nai B’rith leader in Atlanta was convicted of the murder of a 13-year-old Gentile girl, Mary Phagan, whom he had lured to his office and raped before strangling her to death.

Not only did Ochs hand over his newspaper to Frank’s defense but he aided Frank in trying to pin the crimes of rape and murder on two innocent Black men who were Frank’s employees. The Leo Frank case became the founding event of the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith, which exploited the case—the way the Klan exploited Birth of a Nation. Even the ADL’s approved and authorized Leo Frank case scholar admits that the anti-Black racism of Ochs’s Times was unbridled. Steve Oney writes,

[The Times articles] read as if they’d originated from within the defense camp. Which, in many instances, they had. On several occasions during this period, Ochs essentially turned over his news columns to Frank’s lawyers, printing lengthy interviews unmediated by any skepticism and unencumbered by a word from the other side.

In dozens of articles about the case, the Times called one of those Black men, named James Conley,

a “wretched degenerate negro”

a “semi-intoxicated, lustful, improvident, and impecunious negro”

a “drunken degenerate treacherous negro”

a “drunken, obscene, lying, licentious negro jailbird”

A Times correspondent actually interviewed Conley and reported that he was a “heartless, brutal, greedy, literally a black monster, drunken, low-lived, [and] utterly worthless…black human animal” who “growls like a hungry dog…” Noting the several Black witnesses that testified against Frank, Ochs insisted that “negro testimony” was an inferior class of evidence that could not be believed on its face. Further, Ochs’s paper advanced the idea that rape and murder were “negro crimes” and thus Leo Frank—a white man—could not be guilty. Overwhelming evidence showed conclusively that Frank was a habitual sexual deviant, and Ochs’s vitriolic defense of him probably did more to fuel his lynching in 1915 than any other force.

Conclusion

For more than a century the unmatched authority and prestige of the New York Times made its every word believable and unchallengeable. As the journalistic forerunner to Hollywood’s Steppinfetchits and Hattie McDaniels, the Times had an extraordinary influence in shaping national attitudes and policies on race. The role it plays in consciously stalling America’s racial progress is a critical but unexamined element of the Black–Jewish history of America. Blacks have naively looked for their tormenters to appear in white hoods and robes, only to find their most potent opposers are not on horseback but in the high-rise suites of New York posing as “friends.”

The NAACP famously began in Manhattan in 1909 with a few volunteers, some typewriters, and a minuscule operating budget. Its stated goal was to try to change racial opinion, perspectives, and then policies for the betterment of race relations. But they were no match for Ochs’s behemoth on “the great white way” a few blocks to the north. With its 600 employees and mammoth war chest, its articles and editorials reprinted in multiple American and foreign newspapers, Adolph Ochs’s racist onslaught was daily broadcast the world over. The Anti-Defamation League (ADL) specifically gives Adolph Ochs credit for erasing negative images of Jews in newsprint and onstage in America until “the practice had virtually stopped.” As shown above, Ochs amplified every degrading stereotype of Blacks—and all non-Jews, for that matter—and created yet more. For decades his New York Times actively promoted race wars, blamed Blacks for lynchings, glorified the Ku Klux Klan, criticized Black voting and education, supported American concentration camps—effectively shaping the American mind with his particular brand of white supremacy.

The alarming legacy of Adolph Ochs and the Sulzbergers is tarnished far beyond its 125-plus years of corrupt journalistic practices and its uncountable controversies. The poisonous racial record of this Jewish-owned, Jewish-run American institution—the nation’s “paper of record”—must be thoroughly exposed.

NOTES

“‘Negro’ with a Capital ‘N,’” NYT, 7 March 1930, 20. National magazines had long ago made the change. See “Capital ‘N’ Negro Widens,” NYT, 9 March 1930, 21.

Susan E. Tifft and Alex S. Jones, The Trust: The Private and Powerful Family Behind the New York Times (Boston: Little, Brown, 1999), 277–78.

Anti-Defamation League, “1913-1920 ADL – In Retrospect,” History of ADL, 2008, https://web.archive.org/web/20080414191813/http://www.adl.org/ADLHistory/1913_1920.asp.

Steven Bloom, “Interactions Between Blacks and Jews in New York City, 1900-1930, As Reflected in the Black Press” (Ph.D. diss., New York Univ., 1973), 29–30. See NYT, 29 April 1909.

Tifft and Jones, The Trust, 275–78.

Nation of Islam, The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews, vol. 1 (Chicago, 1991), 87, 102, 193, 296–97, 303; Nation of Islam, Jews Selling Blacks (Chicago, 2023), 128–31, 170.

In another Times article (Feb 10, 1906) the Klan is presented thus:

“At that time the celebrated Parson Brownlow was ruler in Tennessee, and the negroes and certain evil white men held the country in terror, burning houses, killing ex-Confederates, and insulting women. When it was observed what terror the members of the Ku Klux (a deliberate corruption of the Greek word Kuklos, a circle,) inspired in the negroes, the social club gradually transformed itself into a band of regulators.”

See also the article “The Black Man North and South,” NYT, 8 Feb. 1903, SM12.

“The Negro and the Law,” editorial, NYT, 14 July 1903, 6.

“Negro Legislators,” NYT, 8 Feb. 1903, 34.

“The ‘Old Mammy’ Market,” NYT, 9 Jan. 1908, 8.

Tifft and Jones, The Trust, 92–96, 816.

Minstrelsy—including the NYT’s “kind of minstrel show version of African American speech”— was purely Caucasian in its origin, and its practice became the domain of Jewish “entertainers,” whose mainstays of entertainment were blackface and “coon shouting.” “Entertainers” like Eddie Cantor, Al Jolson, Irving Berlin, and Florenz Ziegfeld used Black race mockery “as a major modality.” The B’nai B’rith Magazine printed meticulously crafted examples of what it mockingly considered “negro dialect,” in a section of its publication dedicated to “jokes.” See Nation of Islam, Jews Selling Blacks (Chicago, 2023), 221–35.

Having Black maids and servants was a common practice among Jews that extended beyond the boundaries of the South. See “The Bronx Slave Market,” The Crisis [NAACP], September 1935, at https://noirg.org/articles/the-bronx-slave-market-the-crisis-naacp-september-1935/.

New York Age, July 11, 1912.

Jews Selling Blacks, 236.

Broad Ax, Feb. 3, 1912.

Steven Bloom, “Interactions Between Blacks and Jews in New York City, 1900-1930, As Reflected in the Black Press” (Ph.D. diss., New York Univ., 1973), 31. (B.C. Franck is a reference to Ochs’s cousin and partner and Times corporate secretary, Ben C. Franck.)

Bloom, “Interactions Between Blacks and Jews in New York City,” 58.

Samuel Gompers and Herman Gutstadt, Meat vs. Rice: American Manhood Against Asiatic Coolieism, Which Shall Survive? (pamphlet published by American Federation of Labor [and printed as Senate Document 137], 1902; reprint, San Francisco: Asiatic Exclusion League, 1908).

Nation of Islam, The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews, vol. 2, 36–40, 428, 431, 433, 448–50, 453.

Nation of Islam, The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews, vol. 2, 447–59.

NYT, 9 June 1900, 7.

NYT, 6 Nov. 1897, 3.

“Alabama Justice,” NYT, 23 July 1897, 10.

“Negro Lynched in Alabama,” NYT, 17 July 1897, 7.

NYT, 31 July 1910, 1.

NYT, 25 Oct. 1904, 1.

“Drag Body Through Town,” NYT, 1 Dec. 1907, 8. Historically, the public displaying of Black bodies was important to maintaining a sense of terror among the enslaved Black population in America. At the very inception of United States history, famed midnight rider Paul Revere said that he rode past the decayed body of a Black African who had been “hung in chains” in a tree, where it remained for twenty years, shriveling into a mummified remnant. See Esther Forbes, Paul Revere (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1962), 37–39, 258.

“Negro Murderer Lynched,” NYT, 11 Dec. 1897, 4.

“Negro Lynched in Florida,” NYT, 29 April 1909, 6.

An example of the pre-Ochs position is in “Lynching in the South,” NYT, 14 Jan. 1896, 4.

“Mr. Dixon’s The Leopard’s Spots,” NYT, 5 April 1902, BR10; “Ku Klux Klan,” NYT, 21 Jan. 1905, BR34. See also “Mr. Dixon’s Latest Ku Klux Novel,” NYT, 3 Aug. 1907, BR475; “Atlanta Views on Riots,” NYT, 24 Sept. 1906, 2.

Nation of Islam, The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews, vol. 2, 414.

John S. Terry, “Lynchings in the South,” letter to the editor, NYT, 16 July 1922.

Robert Rockaway, review of Prostitution and Prejudice: The Jewish Fight Against White Slavery, 1870-1939, by Edward J. Bristow, in Studies in Contemporary Jewry, vol. 2, ed. Peter Y. Medding (Bloomington, IN: Indiana Univ. Press, 1986), 310. Also, see the discussion of how the crime of rape is treated by the ancient Talmudic rabbis, in Judith Romney Wegner, Chattel or Person? The Status of Women in the Mishnah (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1988), 22–28. Of 126 “disreputable houses” investigated in New York, Jews constituted the “largest number of proprietors.” See Jean Ulitz Mensch, “Social Pathology in Urban America: Desertion, Prostitution, Gambling, Drugs and Crime among Eastern European Jews in New York City between 1881 and World War I” (Ph.D. diss., Columbia Univ., 1983), 77.

Nation of Islam, The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews, vol. 2, 462–63.

Nation of Islam , The Secret Relationship Between Blacks and Jews, vol. 3, passim.

Steve Oney, And the Dead Shall Rise: The Murder of Mary Phagan and the Lynching of Leo Frank (New York: P2antheon Books, 2003), 373–74. Oney (pp. 426, 457) calls it “the paper’s unremitting partisanship.” “Ochs’s sheet was more interested in disseminating propaganda than in practicing journalism.” The Times “presented a shrill and one-sided picture of the facts.”

“Rand Paul battles Kamala Harris and Cory Booker on anti-lynching bill,” https://www.politico.com/news/2020/06/04/rand-paul-anti-lynching-bill-301617.

“List of The New York Times controversies,” 11 September 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_The_New_York_Times_controversies.