For years, Tucker Carlson had been the highest-rated host on television, courageously covering the important, controversial topics that few others dared to touch. After his forced departure from FoxNews in April 2023, he soon launched an even bolder interview show on Elon Musk’s Twitter platform, now completely free of the timorous corporate oversight and time constraints that have always crippled network TV.

For years, Tucker Carlson had been the highest-rated host on television, courageously covering the important, controversial topics that few others dared to touch. After his forced departure from FoxNews in April 2023, he soon launched an even bolder interview show on Elon Musk’s Twitter platform, now completely free of the timorous corporate oversight and time constraints that have always crippled network TV.

His most remarkable achievement came in February of this year, when he traveled to Moscow and conducted a two hour sit down interview with Russian President Vladimir Putin, with many tens of millions worldwide watching the unfiltered responses of one of the top global figures of our young twenty-first century. An interview of such historic significance might have left Walter Cronkite green with envy during the heyday of network television, and with today’s cable news ratings in free fall, Carlson’s former TV colleagues could only sputter with envious rage and denounce their hugely successful competitor as “a Russian stooge.”

Carlson’s September 2nd interview with Darryl Cooper was hardly in the same category, given the relative obscurity of his guest, an amateur historian and podcaster. I’d never heard of Cooper nor had most others, but the explosive subject matter of the discussion partly made up for that lack. The lead item was the Jonestown Cult that had perished in a notorious 1978 mass suicide, and perhaps a half-hour of the 140 minute session was devoted to that. But much of the remainder dealt with World War II, Adolf Hitler, and Winston Churchill, and the candid and controversial treatment of those momentous topics soon set off fireworks all across the Internet.

I don’t use Twitter myself, but within 24 hours that platform was apparently ablaze about the interview, with former Rep. Liz Cheney among many others Tweeting out her outrage, and ADL President Jonathan Greenblatt endorsing and amplifying her attack. Twitter owner Elon Musk, the world’s wealthiest man, promoted the interview as “Very interesting. Worth watching” to his nearly 200 million followers but a blizzard of attacks soon forced him to delete that Tweet. By the 5th, the Washington Post had broken its own rules to publish an editorial denouncing both Carlson and his guest, as did a conservative columnist in the same publication, along with various other prominent commentators.

On September 6th, the New York Times heavily weighed in, publishing two very negative news stories as well as an opinion column on the swirling controversy, which was how I first learned about what had transpired. Although the history of World War II has been a topic of great interest to me, I was busy with my own work, so I merely glanced at the headlines and completely missed the dozen or two dozen other articles that soon appeared in a variety of different publications.

Most of those headlines were certainly explosive and easily explained the vast outpouring of heated words that soon blazed across social media and the rest of the Internet. The ones appearing in the Times were fairly typical of the rest:

The term “Holocaust Revisionist” is usually little more than a euphemistic version of the much harsher term “Holocaust Denier,” and a large majority of the other articles adopted that latter formulation, both in their titles and in their text. Based upon all this news media coverage, the White House issued a statement fiercely attacking both Carlson and Cooper:

…[G]iving a microphone to a Holocaust denier who spreads Nazi propaganda is a disgusting and sadistic insult to all Americans, to the memory of the over 6 million Jews who were genocidally murdered by Adolf Hitler, to the service of the millions of Americans who fought to defeat Nazism, and to every subsequent victim of antisemitism…. Hitler was one of the most evil figures in human history and the ‘chief villain’ of World War II, full stop…. The Biden-Harris administration believes that trafficking in this moral rot is unacceptable at any time, let alone less than one year after the deadliest massacre perpetrated against the Jewish people since the Holocaust and at a time when the cancer of antisemitism is growing all over the world.

Just over six years ago, I had published a very lengthy article analyzing the origins and history of that extremely controversial ideological movement, and towards the beginning I’d described the role it played in our society:

For decades, Hollywood has sanctified the Holocaust, and in our deeply secular society accusations of Holocaust Denial are a bit like shouting “Witch!” in Old Salem or leveling accusations of Trotskyism in the Court of the Red Czar.

Such sentiments remain just as strong today, and according to the huge wave of media stories a real, live Holocaust Denier—something almost as rare as the fabled unicorn—had not only been featured on Carlson’s enormously popular podcast show, but had even been favorably highlighted by Elon Musk. Under these circumstances, the vast media furor that resulted was hardly unwarranted.

A few days later I finally had some time to watch the long interview, which has now attracted more than a million views on YouTube, while the Tweet separately providing the same video has been viewed nearly 35 million times.

Just as I had half-expected, what I actually saw was quite different than what most of the news coverage had suggested, once again completely affirming my belief in the total incompetence of our mainstream media.

Most of the writers had fiercely attacked Carlson for giving an admiring interview to a Holocaust Denier, yet when I carefully listened to the more than two hours of discussion, I heard not a single mention of that topic, nor any denial of the Nazi slaughter of Jews during World War II. It seemed that nearly all the journalists denouncing the show had just been too lazy to bother listening to what Cooper actually said, or perhaps too emotionally agitated to understand the plain meaning of his words.

A few of Cooper’s angry critics seemed to have avoided such a gigantic blunder and were properly circumspect. But anyone reading the New York Times or the Wall Street Journal or the Washington Post, listening to CNN, or crediting the public statements issued by the White House would have been absolutely convinced that a fervent Holocaust Denier had been given a huge global media platform to promote his diabolical views.

As far as I could tell, virtually all the published reactions to the Carlson-Cooper discussion were intensely hostile, and this was true across every website and publication, whether written by liberals or by conservatives, running as news stories or as opinion columns.

However, the mission statement of our own publication is to provide “Interesting, Important, and Controversial Perspectives Largely Excluded from the American Mainstream Media,” and this unbalanced situation provided a perfect opportunity for us to fulfill that mandate. So within a few days we had published or republished three pieces providing a very different perspective on the controversy, each of them considerably more substantial than nearly all the heated but rather vacuous denunciations on the other side. The author of the first of these was actually a prominent Holocaust Denier, while the other two largely avoided that particular issue while expressing their strong support for Cooper’s views and being very encouraged by the enormous attention he had now received.

Although the central focus of almost all the attacks on Cooper had been the belief that he was a Holocaust Denier, there seemed no evidence of this, or at least my cursory examination of his previous body of work found nothing. For example, in 2022 he had hosted an “Ask Me Anything” session on his Substack which provoked more than 600 Q&A comments, and when I did a CTRL-F for the word “Holocaust” nothing appeared. His English-language Wikipedia page seems to have disappeared and reading the German one in automatic translation merely provided a laundry-list of the media accusations but without any evidence that they were accurate.

Indeed, after receiving the first wave of those angry accusations and attacks, he almost immediately released a half-hour podcast entitled “My response to the mob” in which he recounted with considerable emotion some of the horrors of the Jewish Holocaust. He heavily cited the very mainstream scholarship of Prof. Timothy Snyder and also told the story of the notorious Babi Yar massacre of some 30,000 Jewish civilians near Kiev by the fiendish Nazis. Cooper’s actual World War II podcast series will not be released until next year, but given all of this material and his actual statements in the Carlson interview, there seems no particular reason to believe that his coverage of the Holocaust will differ significantly from the orthodox current narrative.

The likely trigger for the apparently erroneous and almost deranged attacks against Cooper by so many journalists is not hard to understand. In his interview, he discussed the historical reality that the Germans had initially captured some three million Soviet POWs during the enormously successful initial stages of their Barbarossa invasion and lacking the necessary resources to feed them, a majority soon starved to death in the huge camps to which they were confined. Although Cooper severely blamed Hitler for not having properly prepared for such a situation, he also emphasized that their deaths were entirely unintentional.

I suspect that few of those agitated media pundits were aware of this unfortunate but solidly-established history of the Soviet POWs, and they instead automatically assumed that any mention of “millions of deaths” during World War II must necessarily refer to Jews, so the claim that those deaths were unintentional was seen as blatant Holocaust Denial. Combine that with Cooper’s argument that Churchill rather than Hitler was the main villain responsible for the war, and that mistaken conclusion appeared undeniable. When most journalists are total ignoramuses, with hair-trigger reactions to any deviation from the usual narrative of the “Good War,” this sort of error can only be expected.

Something fairly similar had recently happened to rightwing black pundit Candace Owens, who was falsely accused of being a Holocaust Denier, and then emphatically denied those charges in various interviews, including this one with Piers Morgan:

Of all the many attacks against Cooper, the only one that seemed to raise fully legitimate concerns was a 3,100 word critique entitled “History and Anti-History” by Niall Ferguson, a distinguished British historian formerly at Harvard University but now ensconced at Stanford’s Hoover Institution.

Ferguson had never previously heard of Cooper, and after being told that the podcaster was America’s “most important popular historian,” he naturally decided to take a look at the latter’s history books and articles, but discovered that none existed. Instead, Cooper’s only two published works were Twitter — A How to Tips & Tricks Guide (2011) and Bush Yarns and Other Offences (2022), which Ferguson reasonably described as “scarcely works of history.” Carlson had explained that Cooper works “in a different medium—on Substack, X, podcasts” but after carefully listening to the interview, Ferguson declared that he only heard “a series of wild assertions that are almost entirely divorced from historical evidence.” Indeed, he characterized all of this as “the opposite of history: call it anti-history.” His verdict on the medium Cooper chose to use was just as harsh:

Podcasts are not reviving history, as is often claimed these days. They are mostly drowning it in a tidal wave of blather, at best sloppy, at worst mendacious.

I’ve read several of Ferguson’s influential books over the years and found them very good, with the author carefully weighing conflicting evidence and sometimes coming to surprising conclusions, the sort of analytical process that is obviously very difficult if not impossible in a podcast format.

Cooper’s World War II series will probably not be released until next year, but I’ve now listened to a couple of hours of his other podcasts and taken together with his long interview, I think that Ferguson’s criticism has a great deal of merit. The bulk of Cooper’s material consists of flat assertions of fact, with either no source provided or at least no effort made to evaluate the credibility of that source. Controversial historical events tend to produce a vast outpouring of totally conflicting claims and narratives and simply choosing to accept one as the basis of a podcast monologue while ignoring all the others does not constitute serious historiography.

Perhaps I’m being unfair to Cooper, but I don’t have the time to listen to 50 or 100 hours of his other history podcasts, so I’ve been forced to rely upon a very limited sample. Based upon all of this, I think it’s probably incorrect to characterize Cooper as a “popular historian.” Instead, he seems to be a popular “history podcaster,” which is something entirely different.

During the more than two hours of his interview with Carlson, Cooper came across as an extremely intelligent individual, certainly sincere and very well read, and I greatly credited him for successfully piercing the numerous layers of encrusted propaganda that have so totally obscured our understanding of the true history of the Second World War. On many of the important points that he made, I thought he was generally correct and the 99% of our establishment historians who would strongly disagree with him were entirely wrong. But I’m just not sure that he could ever package his contrary analysis in a format that would convince anyone on the other side, let alone a self-confident, solidly established historian such as Ferguson.

Cooper’s apparent lack of academic credentials would hardly help. In his Ask Me Anything, he explained that he’d come from background that seemed rather deprived, growing up in “ghettos, barrios, and trailer parks,” while liking to fight when he was younger. He explained that when 9/11 happened, he was 20 years old and already in the Navy, suggesting that he’d probably gone straight into military service after high school. Self-taught historians lacking a college education have two strikes against them when challenging the settled historical views of an Oxford-educated Ferguson or his peers.

Roughly half of Ferguson’s essay criticized Cooper’s methods and presentation, and I mostly agreed with this, but the remainder challenged his conclusions, and here I thought Cooper was much more right than wrong. I doubt that Ferguson realizes that he may have spent his entire scholarly career within a massive propaganda-bubble whose existence he had never suspected. This reality may be best illustrated by a single, striking example.

I spent most of the early 2000s working on a software project to digitize and present the archives of many of our leading publications of the last 150 years. Although I managed to complete the system, it proved a dismal failure, only attracting the tiniest sliver of the usage and traffic that I’d hoped, apparently because almost no one was interested in looking at old periodicals and magazines. But during that process, I’d occasionally glanced at the material that I was including and I gradually discovered that the true history of our country was radically different than what I’d always believed it to be. As I wrote in 2018:

I sometimes imagined myself a little like an earnest young Soviet researcher of the 1970s who began digging into the musty files of long-forgotten Kremlin archives and made some stunning discoveries. Trotsky was apparently not the notorious Nazi spy and traitor portrayed in all the textbooks, but instead had been the right-hand man of the sainted Lenin himself during the glorious days of the great Bolshevik Revolution, and for some years afterward had remained in the topmost ranks of the Party elite. And who were these other figures—Zinoviev, Kamenev, Bukharin, Rykov—who also spent those early years at the very top of the Communist hierarchy? In history courses, they had barely rated a few mentions, as minor Capitalist agents who were quickly unmasked and paid for their treachery with their lives. How could the great Lenin, father of the Revolution, have been such an idiot to have surrounded himself almost exclusively with traitors and spies?

A couple of years ago I happened to be reading To End All Wars, a highly-regarded account of British peace movements during the First World War written by prize-winning historian Adam Hochschild. At one point, the author noted with dismay that by 1916 all the major governments had become so totally committed to the conflict that any notion of a negotiated peace was utterly unthinkable, despite the many millions of lives that might have been saved. This flabbergasted me since during late 1916 all of America’s leading publications had carried headlines about the huge effort of the German government to achieve a negotiated peace and end the war, an effort that was flatly rejected by the Allies, who were firmly committed to Germany’s destruction.

Because the Allies were totally opposed to any negotiated peace, millions of additional Europeans died and the subsequent outbreak of the Bolshevik Revolution set into motion ideological forces that eventually led to the deaths of tens of millions more. But the Allies did ultimately win the war and since they blamed it upon unflinching German militarism, the story of Germany’s major peace efforts was viewed as “discordant” and tossed down the memory-hole, completely excluded from all of our histories during the one hundred years that followed, so much so that even few academic specialists ever became aware of it. Ferguson seemed to fall into that unfortunate category, and he apparently never uncovered those facts despite the exhaustive research that went into his own excellent book on the First World War. As I wrote in late 2022:

Consider high-profile British-born historian Niall Ferguson of Harvard and Stanford Universities, who had made his early name with his publication of The Pity of War in 1999, a highly heterodox reanalysis of World War I that came to numerous controversial conclusions. Among other positions, Ferguson boldly argued that the British should have stayed out of the conflict, which would then have resulted in a quick and sweeping German victory, leading Germany to establish political and economic hegemony over Continental Europe. But this would have simply resulted in the creation of the EU three generations earlier and avoided the many tens of millions of needless deaths in the two world wars, let alone the global consequences of the Bolshevik Revolution.

Although Ferguson was deliberately provocative in his account, I didn’t remember seeing any specific mention of the 1916 peace proposal when I’d read the book a few years ago, and reexamining it now confirmed my recollection, even though his Introduction contains nearly a page of “What If?” scenarios, and he discussed numerous “alternative realities” later in his text. Indeed, just a couple of years earlier he had edited Virtual History, a collection of more than a dozen lengthy essays by professional scholars examining the consequences of history taking a different turn at numerous key junctures, including a German victory in WWI, but once again it totally lacked any suggestion of a possible negotiated peace in 1916.

An even longer volume of a very similar type, appropriately titled What If? appeared in 2001, edited by historian Robert Cowley and it was just as silent. The book ran over 800 pages, of which more than 90 were devoted to seven different alternate scenarios involving World War I, but the possibility of a 1916 peace nowhere appeared, despite surely being one of the most obvious and important “What Ifs.”

Comprehensive mainstream histories also seemed quite silent. In 1970 renowned British historian A.J.P. Taylor published English History, 1914-45, which ran almost 900 pages, with nearly a quarter of those were devoted to WWI; but no hint was given of the 1916 German peace proposal, with the very possibility of the Germans accepting a reasonable compromise peace at that point being dismissed in just a few sentences and a footnote. John Keegan’s 1999 volume The First World War runs 475 pages and also appears to lack any mention. While I’ve hardly performed an exhaustive review of all the standard historical texts, I think these two examples seem fairly typical, probably thus explaining Hochschild’s complete lack of awareness, with Ferguson and other distinguished authors likely having similar gaps in their knowledge.

The complete Allied rejection of German peace proposals in 1916 was a matter of the greatest importance, yet in true Orwellian fashion all our histories were rewritten to deny that reality, with both intelligent laymen and trained historians remaining completely ignorant of what had happened.

This century-long regime of total silence was only finally broken in 2021 when the very respectable historian Philip Zelikow, best known for having served as executive director of the 9/11 Commission, published The Road Less Traveled, telling that hugely important story for the first time, a project that had intermittently occupied his efforts for the previous dozen years.

Although the main text ran well under 300 pages, his account of events seemed thorough and persuasive in its coverage, drawing heavily upon archival records and private diaries to firmly establish the same remarkable story that I had originally glimpsed in those old publications. His exhaustive research had uncovered a great deal of additional material, piecing together an account radically different than what had been presented in many decades of highly misleading treatments. And despite such seemingly controversial “revisionism,” his work received glowing endorsements from leading academic scholars and favorable reviews in such influential publications as Foreign Affairs, the National Interest, and Foreign Policy, though since it never caught the attention of my newspapers I’d remained unaware of it.

I think a strong case can be made that the complete Allied rejection of German peace proposals in 1916 marked one of the great turning points in twentieth century Western history:

If a negotiated peace had ended the wartime slaughter after just a couple of years, the impact upon the history of the world would obviously have been enormous, and not merely because more than half of the many millions of wartime deaths would have been avoided. All the European countries had originally marched off to battle in early August 1914 confident that the conflict would be a short one, probably ending in victory for one side or the other “before the leaves fell.” Instead, the accumulated changes in military technology and the evenly-balanced strength of the two rival alliances soon produced a gridlock of trench-warfare, especially in the West, with millions dying while almost no ground was gained or lost. If the fighting had stopped in 1916 without a victory by either side, such heavy losses in a totally pointless conflict surely would have sobered the postwar political leadership of all the major European states, greatly discouraging the brinksmanship that had originally led to the calamity let alone allowing any repeat. Many have pointed to 1914 as the optimistic high-water mark of Western Civilization, and with Europe chastened by the terrible impact of two disastrous years of warfare and millions of unnecessary deaths, that peak might have been sustained indefinitely.Instead, the consequences of the continuing war were utterly disastrous for all of Europe and much of the world. Many millions more died, and the difficult wartime conditions probably fostered the spread of the deadly Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918, which then swept across the world, taking as many as 50 million lives. Russia’s crippling defeats in 1917 brought the Bolsheviks to power, leading to a long civil war that killed many millions more, followed by three generations of global conflict over Soviet Communism, certainly accounting for tens of millions of additional civilian deaths. The extremely punitive terms that the Treaty of Versailles imposed upon defeated Imperial Germany in 1919 eventually led to the collapse of the Weimar Republic and a second, far worse round of global warfare involving both Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia, a catastrophe that laid waste to much of Europe and claimed several times as many victims as the Great War itself.

Although the Allies at the time had bitterly denounced what they sometimes called the dangerous “German Peace Offensive” of late 1916, it seemed obvious to me that the world would have been a much better place if it hadn’t been rejected.

Ferguson rather arrogantly boasts that unlike Cooper “I have spent most of my adult life writing history books.” But apparently during all those decades of scholarly research he had remained totally unaware of one of the greatest pivot-points of twentieth century Western history. So perhaps he should be a little less casually dismissive of those historical analyses that sharply differ from the official narrative, even including some of the controversial World War II claims made by Cooper in his interview.

One of the very valid criticisms that Ferguson leveled against Cooper was the lack of any sources the latter provided for his shocking, unorthodox claims, and the British historian strongly suspected that these were highly disreputable ones, perhaps even “old Nazis, making excuses.” But given Cooper’s denunciation of Churchill as the greatest villain of World War II, Ferguson seemed certain that at least some of the books Cooper has relied upon are the ones by David Irving, and I tend to agree with him on that point.

Ferguson clearly despises Irving, describing him as someone “whose remaining reputation as an historian was destroyed in 2000 when he was exposed as Holocaust denier in a libel case that he himself brought against Deborah Lipstadt and Penguin Books.” Ferguson was already an Oxford historian in his mid-thirties at the time of the celebrated Irving trial, but my own analysis of the facts and the outcome are so strikingly different than his I really wonder if he has ever bothered investigating the matter. As I wrote in 2018:

These zealous ethnic-activists began a coordinated campaign to pressure Irving’s prestigious publishers into dropping his books, while also disrupting his frequent international speaking tours and even lobbying countries to bar him from entry. They maintained a drumbeat of media vilification, continually blackening his name and his research skills, even going so far as to denounce him as a “Nazi” and a “Hitler-lover,” just as had similarly been done in the case of Prof. Wilson.

That legal battle was certainly a David-and-Goliath affair, with wealthy Jewish movie producers and corporate executives providing a huge war-chest of $13 million to Lipstadt’s side, allowing her to fund a veritable army of 40 researchers and legal experts, captained by one of Britain’s most successful Jewish divorce lawyers. By contrast, Irving, being an impecunious historian, was forced to defend himself without benefit of legal counsel.In real life unlike in fable, the Goliaths of this world are almost invariably triumphant, and this case was no exception, with Irving being driven into personal bankruptcy, resulting in the loss of his fine central London home. But seen from the longer perspective of history, I think the victory of his tormentors was a remarkably Pyrrhic one.

Although the target of their unleashed hatred was Irving’s alleged “Holocaust denial,” as near as I can tell, that particular topic was almost entirely absent from all of Irving’s dozens of books, and exactly that very silence was what had provoked their spittle-flecked outrage. Therefore, lacking such a clear target, their lavishly-funded corps of researchers and fact-checkers instead spent a year or more apparently performing a line-by-line and footnote-by-footnote review of everything Irving had ever published, seeking to locate every single historical error that could possibly cast him in a bad professional light. With almost limitless money and manpower, they even utilized the process of legal discovery to subpoena and read the thousands of pages in his bound personal diaries and correspondence, thereby hoping to find some evidence of his “wicked thoughts.” Denial, a 2016 Hollywood film co-written by Lipstadt, may provide a reasonable outline of the sequence of events as seen from her perspective.

Yet despite such massive financial and human resources, they apparently came up almost entirely empty, at least if Lipstadt’s triumphalist 2005 book History on Trial may be credited. Across four decades of research and writing, which had produced numerous controversial historical claims of the most astonishing nature, they only managed to find a couple of dozen rather minor alleged errors of fact or interpretation, most of these ambiguous or disputed. And the worst they discovered after reading every page of the many linear meters of Irving’s personal diaries was that he had once composed a short “racially insensitive” ditty for his infant daughter, a trivial item which they naturally then trumpeted as proof that he was a “racist.” Thus, they seemingly admitted that Irving’s enormous corpus of historical texts was perhaps 99.9% accurate.

I think this silence of “the dog that didn’t bark” echoes with thunderclap volume. I’m not aware of any other academic scholar in the entire history of the world who has had all his decades of lifetime work subjected to such painstakingly exhaustive hostile scrutiny. And since Irving apparently passed that test with such flying colors, I think we can regard almost every astonishing claim in all of his books—as recapitulated in his videos—as absolutely accurate.

With the possible exception of Arnold Toynbee, I think Irving probably ranks as the most internationally successful British historian of the last one hundred years, and his seminal original research on World War II has completely transformed our understanding of that conflict over the last half-century. Prior to Irving’s ideological purge and the destruction of his career, millions of his books had already gone into print, and Ferguson might discover some interesting facts if he could bring himself to furtively read one or two of them.

This is particularly true with regard to Irving’s brilliant research on Churchill, a central target of Cooper’s criticism and someone whose career was strongly defended by Ferguson in his rebuttal. Cooper had very briefly alluded to the financial payments that Churchill had received from “financiers” and Ferguson denounced the podcaster for regurgitating notoriously anti-Semitic Nazi propaganda:

Ah yes, of course. Churchill, the puppet of the financiers. Now why does that seem familiar? Well, because it was one of the leitmotifs of Joseph Goebbels’s wartime propaganda.

However, anyone who has bothered reading Irving’s masterworks would be well-aware that Cooper had actually pulled his punches and the historical facts were vastly worse than he ever suggested. As I have explained at length:

I recently decided to tackle one of Irving’s much longer works, the first volume of Churchill’s War, a classic text that runs some 300,000 words and covers the story of the legendary British prime minister to the eve of Barbarossa, and I found it just as outstanding as I had expected.

As one small indicator of Irving’s candor and knowledge, he repeatedly if briefly refers to the 1940 Allied plans to suddenly attack the USSR and destroy its Baku oilfields, an utterly disastrous proposal that surely would have lost the war if actually carried out. By contrast, the exceptionally embarrassing facts of Operation Pike have been totally excluded from virtually all later Western accounts of the conflict, leaving one to wonder which of our numerous professional historians are merely ignorant and which are guilty of lying by omission.

Until recently, my familiarity with Churchill had been rather cursory, and Irving’s revelations were absolutely eye-opening. Perhaps the most striking single discovery was the remarkable venality and corruption of the man, with Churchill being a huge spendthrift who lived lavishly and often far beyond his financial means, employing an army of dozens of personal servants at his large country estate despite frequently lacking any regular and assured sources of income to maintain them. This predicament naturally put him at the mercy of those individuals willing to support his sumptuous lifestyle in exchange for determining his political activities. And somewhat similar pecuniary means were used to secure the backing of a network of other political figures from across all the British parties, who became Churchill’s close political allies.

To put things in plain language, during the years leading up to the Second World War, both Churchill and numerous other fellow British MPs were regularly receiving sizable financial stipends—cash bribes—from Jewish and Czech sources in exchange for promoting a policy of extreme hostility toward the German government and actually advocating war. The sums involved were quite considerable, with the Czech government alone probably making payments that amounted to tens of millions of dollars in present-day money to British elected officials, publishers, and journalists working to overturn the official peace policy of their existing government. A particularly notable instance occurred in early 1938 when Churchill suddenly lost all his accumulated wealth in a foolish gamble on the American stock-market, and was soon forced to put his beloved country estate up for sale to avoid personal bankruptcy, only to quickly be bailed out by a foreign Jewish millionaire intent upon promoting a war against Germany. Indeed, the early stages of Churchill’s involvement in this sordid behavior are recounted in an Irving chapter aptly entitled “The Hired Help.”

Ironically enough, German Intelligence learned of this massive bribery of British parliamentarians, and passed the information along to Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, who was horrified to discover the corrupt motives of his fierce political opponents, but apparently remained too much of a gentlemen to have them arrested and prosecuted. I’m no expert in the British laws of that era, but for elected officials to do the bidding of foreigners on matters of war and peace in exchange for huge secret payments seems almost a textbook example of treason to me, and I think that Churchill’s timely execution would surely have saved tens of millions of lives.

My impression is that individuals of low personal character are those most likely to sell out the interests of their own country in exchange for large sums of foreign money, and as such usually constitute the natural targets of nefarious plotters and foreign spies. Churchill certainly seems to fall into this category, with rumors of massive personal corruption swirling around him from early in his political career. Later, he supplemented his income by engaging in widespread art-forgery, a fact that Roosevelt eventually discovered and probably used as a point of personal leverage against him. Also quite serious was Churchill’s constant state of drunkenness, with his inebriation being so widespread as to constitute clinical alcoholism. Indeed, Irving notes that in his private conversations FDR routinely referred to Churchill as “a drunken bum.”

During the late 1930s, Churchill and his clique of similarly bought-and-paid-for political allies had endlessly attacked and denounced Chamberlain’s government for its peace policy, and he regularly made the wildest sort of unsubstantiated accusations, claiming the Germans were undertaking a huge military build-up aimed against Britain. Such roiling charges were often widely echoed by a media heavily influenced by Jewish interests and did much to poison the state of German-British relations. Eventually, these accumulated pressures forced Chamberlain into the extremely unwise act of providing an unconditional guarantee of military backing to Poland’s irresponsible dictatorship. As a result, the Poles then rather arrogantly refused any border negotiations with Germany, thereby lighting the fuse which eventually led to the German invasion six months later and the subsequent British declaration of war. The British media had widely promoted Churchill as the leading pro-war political figure, and once Chamberlain was forced to create a wartime government of national unity, his leading critic was brought into it and given the naval affairs portfolio.

Following his lightening six-week defeat of Poland, Hitler unsuccessfully sought to make peace with the Allies, and the war went into abeyance. Then in early 1940, Churchill persuaded his government to try strategically outflanking the Germans by preparing a large sea-borne invasion of neutral Norway; but Hitler discovered the plan and preempted the attack, with Churchill’s severe operational mistakes leading to a surprising defeat for the vastly superior British forces. During World War I, Churchill’s Gallipoli disaster had forced his resignation from the British Cabinet, but this time the friendly media helped ensure that all the blame for the somewhat similar debacle at Narvik was foisted upon Chamberlain, so it was the latter who was forced to resign, with Churchill then replacing him as prime minister. British naval officers were appalled that the primary architect of their humiliation had become its leading political beneficiary, but reality is what the media reports, and the British public never discovered this great irony.

This incident was merely the first of the long series of Churchill’s major military failures and outright betrayals that are persuasively recounted by Irving, nearly all of which were subsequently airbrushed out of our hagiographic histories of the conflict. We should recognize that wartime leaders who spend much of their time in a state of drunken stupor are far less likely to make optimal decisions, especially if they are extremely prone to military micro-management as was the case with Churchill.

In the spring of 1940, the Germans launched their sudden armored thrust into France via Belgium, and as the attack began to succeed, Churchill ordered the commanding British general to immediately flee with his forces to the coast and to do so without informing his French or Belgium counterparts of the huge gap he was thereby opening in the Allied front-lines, thus ensuring the encirclement and destruction of their armies. Following France’s resulting defeat and occupation, the British prime minister then ordered a sudden, surprise attack on the disarmed French fleet, completely destroying it and killing some 2,000 of his erstwhile allies; the immediate cause was his mistranslation of a single French word, but this “Pearl Harbor-type” incident continued to rankle French leaders for decades.

Hitler had always wanted friendly relations with Britain and certainly had sought to avoid the war that had been forced upon him. With France now defeated and British forces driven from the Continent, he therefore offered very magnanimous peace terms and a new German alliance to Britain. The British government had been pressured into entering the war for no logical reason and against its own national interests, so Chamberlain and half the Cabinet naturally supported commencing peace negotiations, and the German proposal probably would have received overwhelming approval both from the British public and political elites if they had ever been informed of its terms.

But despite some occasional wavering, Churchill remained absolutely adamant that the war must continue, and Irving plausibly argues that his motive was an intensely personal one. Across his long career, Churchill had had a remarkable record of repeated failure, and for him to have finally achieved his lifelong ambition of becoming prime minister only to lose a major war just weeks after reaching Number 10 Downing Street would have ensured that his permanent place in history was an extremely humiliating one. On the other hand, if he managed to continue the war, perhaps the situation might somehow later improve, especially if the Americans could be persuaded to eventually enter the conflict on the British side.

Since ending the war with Germany was in his nation’s interest but not his own, Churchill undertook ruthless means to prevent peace sentiments from growing so strong that they overwhelmed his opposition. Along with most other major countries, Britain and Germany had signed international conventions prohibiting the aerial bombardment of civilian urban targets, and although the British leader had very much hoped the Germans would attack his cities, Hitler scrupulously followed these provisions. In desperation, Churchill therefore ordered a series of large-scale bombing raids against the German capital of Berlin, doing considerable damage, and after numerous severe warnings, Hitler finally began to retaliate with similar attacks against British cities. The population saw the heavy destruction inflicted by these German bombing raids and was never informed of the British attacks that had preceded and provoked them, so public sentiment greatly hardened against making peace with the seemingly diabolical German adversary.

In his memoirs published a half-century later, Prof. Revilo P. Oliver, who had held a senior wartime role in American Military Intelligence, described this sequence of events in very bitter terms:

Great Britain, in violation of all the ethics of civilized warfare that had theretofore been respected by our race, and in treacherous violation of solemnly assumed diplomatic covenants about “open cities”, had secretly carried out intensive bombing of such open cities in Germany for the express purpose of killing enough unarmed and defenceless men and women to force the German government reluctantly to retaliate and bomb British cities and thus kill enough helpless British men, women, and children to generate among Englishmen enthusiasm for the insane war to which their government had committed them.It is impossible to imagine a governmental act more vile and more depraved than contriving death and suffering for its own people — for the very citizens whom it was exhorting to “loyalty” — and I suspect that an act of such infamous and savage treason would have nauseated even Genghis Khan or Hulagu or Tamerlane, Oriental barbarians universally reprobated for their insane blood-lust. History, so far as I recall, does not record that they ever butchered their own women and children to facilitate lying propaganda….In 1944 members of British Military Intelligence took it for granted that after the war Marshal Sir Arthur Harris would be hanged or shot for high treason against the British people…

Churchill’s ruthless violation of the laws of war regarding urban aerial bombardment directly led to the destruction of many of Europe’s finest and most ancient cities. But perhaps influenced by his chronic drunkenness, he later sought to carry out even more horrifying war crimes and was only prevented from doing so by the dogged opposition of all his military and political subordinates.Along with the laws prohibiting the bombing of cities, all nations had similarly agreed to ban the first use of poison gas, while stockpiling quantities for necessary retaliation. Since Germany was the world-leader in chemistry, the Nazis had produced the most lethal forms of new nerve gases, such as Tabun and Sarin, whose use might have easily resulted in major military victories on both the Eastern and Western fronts, but Hitler had scrupulously obeyed the international protocols that his nation had signed. However, late in the war during 1944 the relentless Allied bombardment of German cities led to the devastating retaliatory attacks of the V-1 flying bombs against London, and an outraged Churchill became adamant that German cities should be attacked with poison gas in counter-retaliation. If Churchill had gotten his way, many millions of British might soon have perished from German nerve gas counter-strikes. Around the same time, Churchill was also blocked in his proposal to bombard Germany with hundreds of thousands of deadly anthrax bombs, an operation that might have rendered much of Central and Western Europe uninhabitable for generations.

I found Irving’s revelations on all these matters absolutely astonishing, and was deeply grateful that Deborah Lipstadt and her army of diligent researchers had carefully investigated and seemingly confirmed the accuracy of virtually every single item.

Irving’s 1987 Churchill book had laid bare his subject’s extremely lavish lifestyle as well as his lack of any solid income, together with the dramatic political consequences of that dangerous combination. This shocking historical picture was fully confirmed in 2015 by a noted financial expert whose book focused entirely on Churchill’s tangled finances, and did so with full cooperative access to his subject’s family archives. The story told by David Lough in No More Champagne is actually far more extreme than what had been described by Irving almost three decades earlier, with the author even suggesting that Churchill’s financial risk-taking was almost unprecedented for anyone in public or private life.

For example, at the very beginning of his book, Lough explains that Churchill became Prime Minister on May 10, 1940, the same day that German forces began their invasion of the Low Countries and France. But aside from those huge military and political challenges, Britain’s new wartime leader also faced an entirely different crisis as well, being unable to cover his personal bills, debt interest, or tax payments, all of which were due at the end of the month, thereby forcing him to desperately obtain a huge secret payment from the same Austrian Jewish businessman who had previously rescued him financially. Stories like this may reveal the hidden side of larger geopolitical developments, which sometimes only come to light many decades later.

Ferguson implies that the stories of the massive, secret payments that Churchill received from Jewish financiers were merely falsehoods concocted by Goebbels’ Nazi Ministry of Propaganda before being credulously accepted and promoted by Cooper. But the historian seems totally unaware that all of these facts were absolutely confirmed in 2015 by Lough, a well-respected Oxford-educated financial expert, whose important archival research was conducted with the full cooperation of the Churchill family. Indeed, Cooper can much better be criticized for ignoring all but the tiniest tip of the iceberg of Churchill’s controversial behavior and activities.

Denouncing Cooper for falsely besmirching Churchill’s reputation was also the central theme of a Piers Morgan interview debate from a few days ago, featuring a couple of totally ignorant podcasters, with some gravitas contributed by Andrew Roberts, a British historian and Churchill biographer. Roberts is best known for having been a wildly enthusiastic promoter of George W. Bush’s 2003 invasion of Iraq, praising Prime Minister Tony Blair for his “Churchillian” support of that totally disastrous policy, arguing that anything else would have been tantamount to “appeasement.”

The two existing volumes of Irving’s masterwork on Churchill total well over 700,000 words and although they are the best source of this important material, reading them would obviously consume weeks of dedicated effort. Cooper’s long podcast series on World War II has not yet been released and it’s not at all clear to me how good it will be when it finally arrives. So for those interested in a far more comprehensive and accurate account of Churchill and his activities, I would strongly recommend some of Irving’s riveting public lectures on that topic, long purged from YouTube but still available on BitChute:

One reason for my skepticism regarding the likely quality of Cooper’s World War II podcast series when finally released is the very serious errors he seemed to make during his interview with Carlson, some of which left him vulnerable to ridicule by Ferguson and his other critics. It’s easy to misspeak during a casual conversation, but that’s exactly why it much better to set down one’s true positions down in clearly written articles, works that can be carefully read and reviewed, so with nothing like that available, I’m forced to take Cooper’s words at their face value. As Ferguson writes:

Now comes what Cooper wishes us to see as his most iconoclastic revelation: that “Churchill was the chief villain of the Second World War,” in the sense that “he was primarily responsible for that war becoming what it did, becoming something other than an invasion of Poland.”

Ferguson notes that the problem with these statements was that Churchill only became a member of the British government on the day that war was declared against Germany. Prior to that, he had merely been a back-bencher, if sometimes a loud and agitated one, and although he certainly did his best to exert anti-German pressure on the government of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, pressure is very different than power. So all the crucial decisions that created the wider war that Cooper so strongly condemns were made by Chamberlain and his cabinet, notably Foreign Minister Lord Halifax. That exact point led Roberts and others to ridicule Cooper’s supposed ignorance during the Piers Morgan debate, a show on which Cooper had refused to appear.

Even after joining Chamberlain’s government, Churchill remained in a subordinate role, only becoming Prime Minister as Hitler’s forces were already beginning the campaign in France that would smash the Allied army and occupy that country. Irving very convincingly argues that Churchill then played a crucial role in prolonging and extending the war after mid-1940, but that seems rather different than what Cooper is saying.

Meanwhile Cooper provided no hint of the role of our own President Franklin Roosevelt, who far more than Churchill was actually the central figure in orchestrating World War II. As I wrote last year:

America had been hit especially hard by the Great Depression and although FDR had reached the White House based upon his promise to end it, after five years in office, his policies had largely failed.The American economy had also been weak in 1914, but once the First World War broke out, the huge needs of the Allied countries boosted our industrial production to new heights, resulting in American prosperity. Similarly, many mainstream history books admit that it was only the outbreak of World War II in 1939 that finally pulled the American economy out of the Great Depression, but they never consider the possibility that FDR might have deliberately provoked the war for that purpose. However, as I wrote in 2018, there seems strong contemporaneous evidence to that effect:

During the 1930s, John T. Flynn was one of America’s most influential progressive journalists, and although he had begun as a strong supporter of Roosevelt and his New Deal, he gradually became a sharp critic, concluding that FDR’s various governmental schemes had failed to revive the American economy. Then in 1937 a new economic collapse spiked unemployment back to the same levels as when the president had first entered office, confirming Flynn in his harsh verdict. And as I wrote last year:Indeed, Flynn alleges that by late 1937, FDR had turned towards an aggressive foreign policy aimed at involving the country in a major foreign war, primarily because he believed that this was the only route out of his desperate economic and political box, a stratagem not unknown among national leaders throughout history. In his January 5, 1938 New Republic column, he alerted his disbelieving readers to the looming prospect of a large naval military build-up and warfare on the horizon after a top Roosevelt adviser had privately boasted to him that a large bout of “military Keynesianism” and a major war would cure the country’s seemingly insurmountable economic problems. At that time, war with Japan, possibly over Latin American interests, seemed the intended goal, but developing events in Europe soon persuaded FDR that fomenting a general war against Germany was the best course of action. Memoirs and other historical documents obtained by later researchers seem to generally support Flynn’s accusations by indicating that Roosevelt ordered his diplomats to exert enormous pressure upon both the British and Polish governments to avoid any negotiated settlement with Germany, thereby leading to the outbreak of World War II in 1939.

The last point is an important one since the confidential opinions of those closest to important historical events should be accorded considerable evidentiary weight. In a recent article John Wear mustered the numerous contemporaneous assessments that implicated FDR as a pivotal figure in orchestrating the world war by his constant pressure upon the British political leadership, a policy that he privately even admitted could mean his impeachment if revealed. Among other testimony, we have the statements of the Polish and British ambassadors to Washington and the American ambassador to London, who also passed along the concurring opinion of Prime Minister Chamberlain himself. Indeed, the German capture and publication of secret Polish diplomatic documents in 1939 had already revealed much of this information, and William Henry Chamberlin confirmed their authenticity in his 1950 book. But since the mainstream media never reported any of this information, these facts remain little known even today.

So according to Flynn’s January 1938 account, FDR and his advisors had originally viewed a possible war with Japan as the key to America’s economic revival, but they subsequently shifted their focus to a European war against Germany instead, and I think a turning point may have been the widespread Kristallnacht riots against German Jews in November 1938, following the assassination of a German diplomat by a Jewish activist. These attacks outraged the very influential Jewish communities of America and Europe, completely undoing any positive consequences of the Munich Agreement a couple of months earlier and focused intense international hostility against Hitler’s Germany, which had previously worked out reasonably amicable relations with its small Jewish population while establishing an important economic partnership with the rising Zionist movement.Ironically enough, according to Irving’s very detailed reconstruction, Hitler had nothing to do with the anti-Jewish riots and urgently sought to suppress them once they began. Instead, the attacks seem to have been orchestrated by Joseph Goebbels, his powerful Propaganda Minister, who had recently fallen from favor because of his high-profile love affair with a Czech actress, leading to the bitter complaints of his wife, a close friend of Hitler. Goebbels apparently hoped he could use the anti-Jewish riots to restore his influence in the Nazi hierarchy, but they instead had disastrous consequences, thus raising the remarkable possibility that the political fallout from an extra-marital affair may have played a crucial role in the outbreak of World War II.

During the entire period prior to the outbreak of World War II, FDR was the president of the United States, someone with enormous influence over Britain’s government, while Churchill was merely an agitated back-bencher. Although both of these individuals were pressing for a war against Nazi Germany, it’s rather obvious which of them had greater influence in determining that outcome.

Ferguson also disapprovingly quotes Cooper’s claims regarding Churchill’s later efforts:

[Churchill] also had a dastardly plan to “drag us [the United States] into that war,” using covert “media and propaganda operations.”

Cooper’s statement is a serious distortion of the well-established historical facts. From the very first, FDR was extremely eager to have America join the war against Germany whose outbreak he had successfully orchestrated, but he was held back by Congress and the American people, who were overwhelmingly on the other side. Therefore, our president worked closely with the British to overcome that domestic opposition by methods both fair and foul, which he privately admitted would lead to his impeachment if they ever came to light.

Numerous mainstream histories have discussed these facts, and Churchill’s efforts actually went far beyond merely “media and propaganda operations.” Historian Thomas Mahl’s excellent 1998 book Desperate Deception provided the remarkable details of the secret British espionage operation used to destroy FDR’s political opponents and his anti-war critics, which probably helped secure the 1940 Republican nomination for anti-isolationist Democrat Wendell Willkie, one of the most bizarre political twists in all of American history.

FDR even illegally ordered the US navy to regularly attack German vessels in hopes of provoking Hitler to declare war and when that failed, he provoked the Japanese to attack Pearl Harbor, as I have discussed:

From 1940 onward, FDR had been making a great political effort to directly involve America in the war against Germany, but public opinion was overwhelmingly on the other side, with polls showing that up to 80% of the population were opposed. All of this immediately changed once the Japanese bombs dropped on Hawaii, and suddenly the country was at war.Given these facts, there were natural suspicions that Roosevelt had deliberately provoked the attack by his executive decisions to freeze Japanese assets, embargo all shipments of vital fuel oil supplies, and rebuff the repeated requests by Tokyo leaders for negotiations. In the 1953 volume edited by Barnes, noted diplomatic historian Charles Tansill summarized his very strong case that FDR sought to use a Japanese attack as his best “back door to war” against Germany, an argument he had made the previous year in a book of that same name. Over the decades, the information contained in private diaries and government documents seems to have almost conclusively established this interpretation, with Secretary of War Henry Stimson indicating that the plan was to “maneuver [Japan] into firing the first shot.” In his later memoirs, Prof. Oliver drew upon the intimate knowledge he had acquired during his wartime role in Military Intelligence to even claim that FDR had deliberately tricked the Japanese into believing he planned to launch a surprise attack against their forces, thereby persuading them to strike first in self-defense.

By 1941 the U.S. had broken all the Japanese diplomatic codes and was freely reading their secret communications. Therefore, there has also long existed the widespread if disputed belief that the president was well aware of the planned Japanese attack on our fleet and deliberately failed to warn his local commanders, thereby ensuring that the resulting heavy American losses would produce a vengeful nation united for war. Tansill and a former chief researcher for the Congressional investigating committee made this case in the same 1953 Barnes volume, and the following year a former US admiral published The Final Secret of Pearl Harbor, providing similar arguments at greater length. This book also included an introduction by one of America’s highest-ranking World War II naval commanders, who fully endorsed the controversial theory.

In 2000, journalist Robert M. Stinnett published a wealth of additional supporting evidence, based upon his eight years of archival research, which was discussed in a recent article. A telling point made by Stinnett is that if Washington had warned the Pearl Harbor commanders, their resulting defensive preparations would have been noticed by the local Japanese spies and relayed to the approaching task force; and with the element of surprise lost, the attack probably would have been aborted, thus frustrating all of FDR’s long-standing plans for war. Although various details may be disputed, I find the evidence for Roosevelt’s foreknowledge quite compelling.

I noticed another strange omission in Cooper’s discussion of the war. He severely condemned Hitler for having failed to properly prepare for the vast number of Soviet POWs he seized during the early stages of Barbarossa in 1941. As Ferguson quotes portions of the transcript:

They launched a war where they were completely unprepared. Millions of prisoners of war, of local political prisoners and so forth, that they were going to have to handle. They went in with no plan for that. And they just threw these people into camps. And millions of people ended up dead there. You know, you have, you have like, letters, as early as July, August 1941, from commandants of these makeshift camps …they’re writing back to the high command in Berlin, saying, “We can’t feed these people, we don’t have the food to feed these people.”

Cooper’s description is entirely correct, though he failed to mention that Hitler attempted to negotiate Soviet food assistance for their own POWs via the Red Cross. However, the Stalin had never been willing to sign the Geneva Convention and he flatly rejected the German request, instead declaring that all Soviet POWs were traitors, who should be left to their fate. Meanwhile, captured Germans often suffered even worse losses, with 95% of the troops later captured at Stalingrad dying in Soviet hands. However, there is a far more important matter that Cooper seems to entirely ignore, though I assume he must be aware of it.

When Ferguson was still a young Cambridge don in May 1990, he must surely have noticed that the prestigious Times Literary Supplement had devoted nearly the whole of its biweekly books page to a long review of Icebreaker, a newly published book of potentially enormous importance, a work that boldly sought to overturn our entire settled history of the Second World War. A later edition quoted a portion of that resounding review:

[Suvorov] is arguing with every book, every article, every film, every NATO directive, every Downing Street assumption, every Pentagon clerk, every academic, every Communist and anti-Communist, every neoconservative intellectual, every Soviet song, poem, novel and piece of music ever heard, written, made, sung, issued, produced, or born during the last 50 years. For this reason, Icebreaker is the most original work of history it has been my privilege to read.

As I explained in my 2018 article:

Icebreaker‘s author, writing under the pen-name Viktor Suvorov, was a veteran Soviet military intelligence officer who had defected to the West in 1978 and subsequently published a number of well-regarded books on the Soviet military and intelligence services. But here he advanced a far more radical thesis.

The “Suvorov Hypothesis” claimed that during the summer of 1941 Stalin was on the very verge of mounting a massive invasion and conquest of Europe, while Hitler’s sudden attack on June 22nd of that year was intended to forestall that looming blow.

Since 1990, Suvorov’s works have been translated into at least 18 languages and an international storm of scholarly controversy has swirled around the Suvorov Hypothesis in Russia, Germany, Israel, and elsewhere. Numerous other authors have published books in support or more often strong opposition, and even international academic conferences have been held to debate the theory. But our own English-language media has almost entirely blacklisted and ignored this ongoing international debate, to such an extent that the name of the most widely-read military historian who ever lived had remained totally unknown to me.Finally in 2008, the prestigious Naval Academy Press of Annapolis decided to break this 18 year intellectual embargo and published an updated English edition of Suvorov’s work. But once again, our media outlets almost entirely averted their eyes, and only a single review appeared in an obscure ideological publication, where I chanced to encounter it. This conclusively demonstrates that throughout most of the twentieth century a united front of English-language publishers and media organs could easily maintain a boycott of any important topic, ensuring that almost no one in America or the rest of the Anglosphere would ever hear of it. Only with the recent rise of the Internet has this disheartening situation begun to change.

The Eastern Front was the decisive theater of World War II, involving military forces vastly larger than those deployed in the West or the Pacific, and the standard narrative always emphasizes the ineptitude and weakness of the Soviets. On June 22, 1941, Hitler launched Operation Barbarossa, a sudden, massive surprise attack on the USSR, which caught the Red Army completely unaware. Stalin has been regularly ridiculed for his total lack of preparedness, with Hitler often described as the only man the paranoid dictator had ever fully trusted. Although the defending Soviet forces were enormous in size, they were poorly led, with their officer corps still not recovered from the crippling purges of the late 1930s, and their obsolete equipment and poor tactics were absolutely no match for the modern panzer divisions of Germany’s hitherto undefeated Wehrmacht. The Russians initially suffered gigantic losses, and only the onset of winter and the vast spaces of their territory saved them from a quick defeat. After this, the war seesawed back-and-forth for four more years, until superior numbers and improved tactics finally carried the Soviets to the streets of a destroyed Berlin in 1945.Such is the traditional understanding of the titanic Russo-German struggle that we see endlessly echoed in every newspaper, book, television documentary, and film around us.

But Suvorov’s seminal research argued that the reality was entirely different.

First, although there has been a widespread belief in the superiority of Germany’s military technology, its tanks and its planes, this is almost entirely mythological. In actual fact, Soviet tanks were far superior in main armament, armor, and maneuverability to their German counterparts, so much so that the overwhelming majority of panzers were almost obsolescent by comparison. And the Soviet superiority in numbers was even more extreme, with Stalin deploying many times more tanks than the combined total of those held by Germany and every other nation in the world: 27,000 against just 4,000 in Hitler’s forces. Even during peacetime, a single Soviet factory in Kharkov produced more tanks in every six month period than the entire Third Reich had built prior to 1940. The Soviets held a similar superiority, though somewhat less extreme, in their ground-attack bombers. The totally closed nature of the USSR meant that such vast military forces remained entirely hidden from outside observers.There is also little evidence that the quality of Soviet officers or military doctrine fell short. Indeed, we often forget that history’s first successful example of a “blitzkrieg” in modern warfare was the crushing August 1939 defeat that Stalin inflicted upon the Japanese 6th Army in Outer Mongolia, relying upon a massive surprise attack of tanks, bombers, and mobile infantry.

Certainly, many aspects of the Soviet military machine were primitive, but exactly the same was true of their Nazi opponents. Perhaps the most surprising detail about the technology of the invading Wehrmacht in 1941 was that its transportation system was still almost entirely pre-modern, relying upon wagons and carts drawn by 750,000 horses to maintain the vital flow of ammunition and replacements to its advancing armies.

During Spring 1941 the Soviets had assembled a gigantic armored force on Germany’s border, one that even contained enormous numbers of specialized tanks whose unusual characteristics clearly demonstrated Stalin’s purely offensive aims. For example, the Soviet juggernaut included 6,500 high-speed autobahn tanks, almost useless within Soviet territory but ideally suited for deployment on Germany’s network of highways and 4,000 amphibious tanks, possibly able to navigate the English Channel and conquer Britain.

The Soviets also fielded many thousands of heavy tanks, intended to engage and defeat enemy armor, while the Germans had none at all. In direct combat, a Soviet KV-1 or KV-2 could easily destroy four or five of the best German tanks, while remaining almost invulnerable to enemy shells. Suvorov recounts the example of a KV which took 43 direct hits before finally becoming incapacitated, surrounded by the hulks of the ten German tanks it had first managed to destroy.

Suvorov’s reconstruction of the weeks directly preceding the outbreak of combat is a fascinating one, emphasizing the mirror-image actions taken by both the Soviet and German armies. Each side moved its best striking units, airfields, and ammunition dumps close to the border, ideal for an attack but very vulnerable in defense. Each side carefully deactivated any residual minefields and ripped out any barbed wire obstacles, lest these hinder the forthcoming attack. Each side did its best to camouflage their preparations, talking loudly about peace while preparing for imminent war. The Soviet deployment had begun much earlier, but since their forces were so much larger and had far greater distances to cross, they were not yet quite ready for their attack when the Germans struck, and thereby shattered Stalin’s planned conquest of Europe.All of the above examples of Soviet weapons systems and strategic decisions seem very difficult to explain under the conventional defensive narrative, but make perfect sense if Stalin’s orientation from 1939 onward had always been an offensive one, and he had decided that summer 1941 was the time to strike and enlarge his Soviet Union to include all the European states, just as Lenin had originally intended. And Suvorov provides many dozens of additional examples, building brick by brick a very compelling case for this theory.

Given the long years of trench warfare on the Western front during the First World War, almost all outside observers expected the new round of the conflict to follow a very similar static pattern, gradually exhausting all sides, and the world was shocked when Germany’s innovative tactics allowed it to achieve a lightening defeat of the allied armies in France during 1940. At that point, Hitler regarded the war as essentially over, and was confident that the extremely generous peace terms he immediately offered the British would soon lead to a final settlement. As a consequence, he returned Germany to a regular peacetime economy, choosing butter over guns in order to maintain his high domestic popularityStalin, however, was under no such political constraints, and from the moment he had signed his long-term peace agreement with Hitler in 1939 and divided Poland, he ramped up his total-war economy to an even higher notch. Embarking upon an unprecedented military buildup, he focused his production almost entirely upon purely offensive weapons systems, while even discontinuing those armaments better suited for defense and dismantling his previous lines of fortifications. By 1941, his production cycle was complete, and he made his plans accordingly.

And so, just as in our traditional narrative, we see that in the weeks and months leading up to Barbarossa, the most powerful offensive military force in the history of the world was quietly assembled in secret along the German-Russian border, preparing for the order that would unleash its surprise attack. The enemy’s unprepared airforce was to be destroyed on the ground in the first days of the battle, and enormous tank columns would begin deep penetration thrusts, surrounding and trapping the opposing forces, achieving a classic blitzkrieg victory, and ensuring the rapid occupation of vast territories. But the forces preparing this unprecedented war of conquest were Stalin’s, and his military juggernaut would surely have seized all of Europe, probably soon followed by the remainder of the Eurasian landmass.

Then at almost the last moment, Hitler suddenly realized the strategic trap into which he had fallen, and ordered his heavily outnumbered and outgunned troops into a desperate surprise attack of their own on the assembling Soviets, fortuitously catching them at the very point at which their own final preparations for sudden attack had left them most vulnerable, and thereby snatching a major initial victory from the jaws of certain defeat. Huge stockpiles of Soviet ammunition and weaponry had been positioned close to the border to supply the army of invasion into Germany, and these quickly fell into German hands, providing an important addition to their own woefully inadequate resources.

For those who prefer to absorb Suvorov’s information in a different format, his October 2009 public lecture at the U.S. Naval Academy is available on YouTube:

Earlier that same year his lecture at the Woodrow Wilson Center had been broadcast on C-SPAN Book TV.

I naturally read some of the books purportedly claiming to refute Suvorov’s thesis, such as those by historians David M. Glantz and Gabriel Gorodetsky, but found them rather unpersuasive.

A far superior book, generally supportive of Suvorov’s framework, was Stalin’s War of Annihilation, by prize-winning German military historian Joachim Hoffmann, originally commissioned by the German Armed Forces and published in 1995 with an English revised edition appearing in 2001. The cover carries a notice that the text was cleared by German government censors, and the author’s introduction recounts the repeated threats of prosecution he endured from elected officials and the other legal obstacles he faced, while elsewhere he directly addresses himself to the unseen government authorities whom he knows are reading over his shoulder. When stepping too far outside the bounds of accepted history carries the serious risk that a book’s entire print-run will be burned and the author imprisoned, a reader must necessarily be cautious at evaluating the text since important sections have been skewed or preemptively excised in the interests of self-preservation. Scholarly debates on historical issues become difficult when one side faces incarceration if their arguments are too bold.

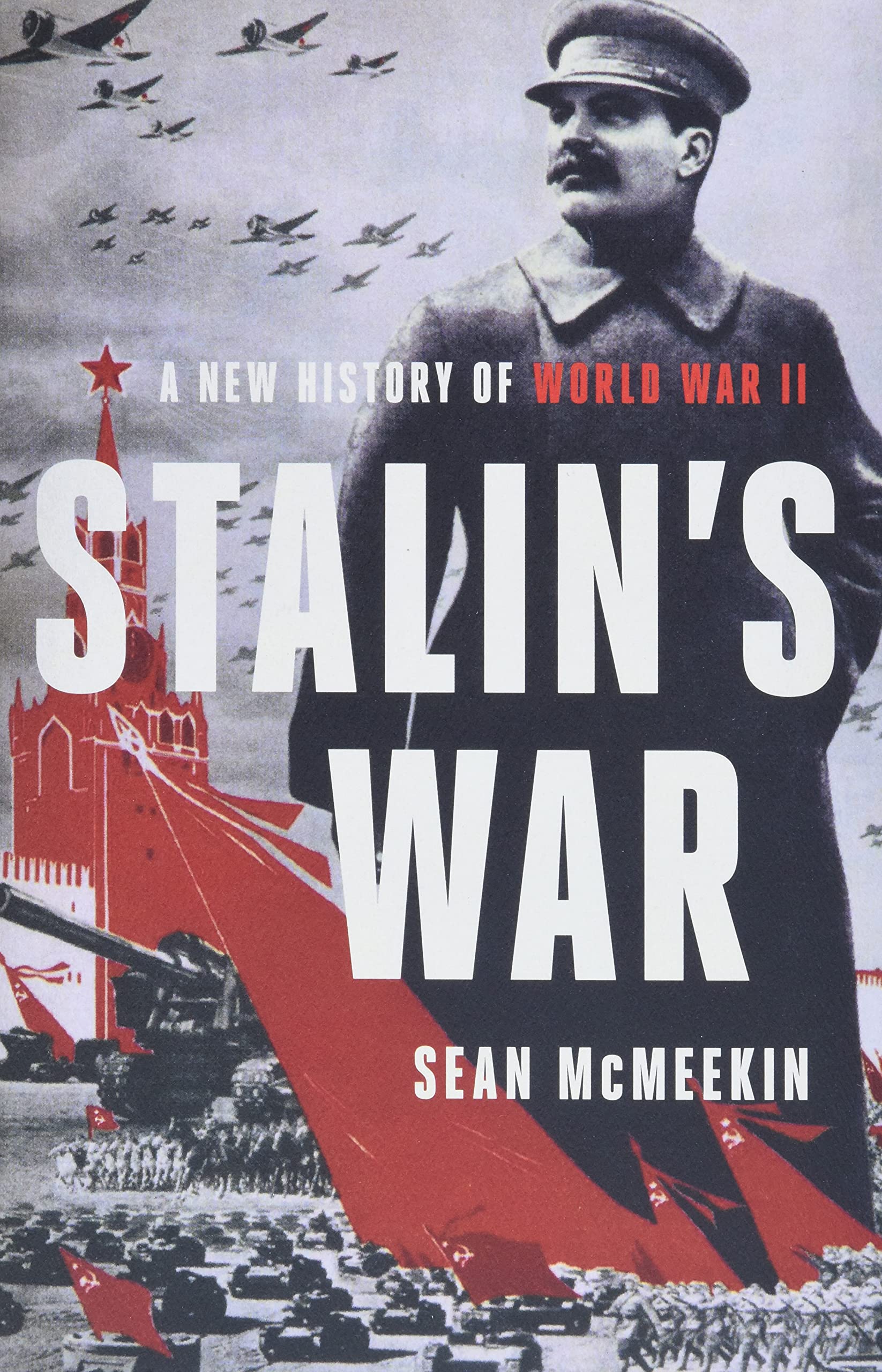

Sean McMeekin is Francis Flournoy Professor of European History and Culture at Bard College and the prize-winning author of a number of highly-regarded books mostly on Russian and Soviet history. After many years of archival research, he published his outstanding 2021 history Stalin’s War, a work that runs well over 800 pages and provided a wealth of additional evidence strongly supporting the Suvorov Hypothesis that the Soviet dictator had massed his enormous offensive forces on the German border and was probably preparing to invade and conquer Europe when Hitler struck first.

More than three decades earlier, that original 1990 Times of London review of Icebreaker had been written by Andrei Navrozov, a Soviet emigre long resident in Britain. As a Russian Slav, he was hardly favorable to the German dictator, but he accepted Suvorov’s remarkable theory that only Hitler’s Barbarossa attack had forestalled Stalin’s conquest of all Europe and he closed his twentieth anniversary discussion with a ringing declaration:

Therefore, if any of us is free to write, publish, and read this today, it follows that in some not inconsequential part our gratitude for this must go to Hitler. And if someone wants to arrest me for saying what I have just said, I make no secret of where I live.

Almost the entire furor regarding Darryl Cooper’s interview revolved around the media claim that Tucker Carlson had hosted a Holocaust Denier, and as we have already discussed, that accusation seemed entirely false. I have no reason to believe that either Cooper or Carlson have views on the Holocaust that substantially deviate from our standard narrative, and I’m sure that if journalists would bother to ask them, they would readily confirm that fact.

However, Ferguson seems deeply suspicious on that score, wondering why the Jewish Holocaust had not been heavily discussed in their lengthy exchange:

Note that at no point in their conversation do Carlson and Cooper mention the Holocaust. The word genocide is never uttered. They talk about Jews a good deal, but not as the principal victims of Hitler’s lethal racial policies.The last time I heard this kind of thing was when the full extent of the Wehrmacht’s complicity in mass murder was being exposed in the 1980s and 1990s. The people who made these arguments were old Nazis, making excuses. And that is what we have here, reheated and served up to an American audience: Nazi excuses. The well-documented reality is that the mass murder, including systematic starvation, of soldiers and civilians in the German-occupied Soviet territory was ideologically motivated and deliberately planned.

In effect, Ferguson is accusing Carlson and Cooper of “Implicit Holocaust Denial,” namely not mentioning what was obviously an absolutely central element of World War II, the shocking murder of some six million helpless Jewish civilians, mostly in gas chambers, something that certainly constituted the greatest wartime atrocity in all of human history.

Yet oddly enough, Ferguson could level exactly those same very harsh accusations against far greater historical figures. Robert Faurisson, a French academic who became a prominent Holocaust Denier in the 1970s, once made an extremely interesting observation regarding the memoirs of Eisenhower, Churchill, and De Gaulle: