Months after the assault on Pearl Harbor, a Japanese American fishing neighborhood on San Pedro’s Terminal Island was given 48 hours to pack its belongings earlier than it was compelled into incarceration camps all through the West. After the evacuation, most of its village was razed.

However for greater than 80 years, two buildings have been left standing. Now, the unique residents, their households and supporters have mobilized to guard the final vestiges of their historical past on Tuna Road.

Tim Yamamoto’s grandfather leased one of many buildings — a grocery retailer that fed the fishermen and cannery employees chargeable for stocking locations similar to StarKist Tuna and Van Camp Seafood. The second constructing subsequent door was a dry items store. Each are owned by the Port of Los Angeles.

When Yamamoto, 66, realized that the related buildings could also be demolished, he was compelled to take motion in honor of his late mother and father, who grew up on Terminal Island and married at one of many incarceration camps.

Tim Yamamoto surveys the final remaining buildings within the previous Japanese fishing village of Terminal Island.

(Al Seib / For The Occasions)

“These buildings present that there was one thing right here. If they’re worn out, then any hint of the Terminal Island historical past is gone,” he mentioned. “I simply wish to do one thing to maintain some type of historical past alive.”

Members of the Terminal Islanders membership — a bunch of practically 200 folks that Yamamoto belongs to — realized of doable plans for the buildings when an area San Pedro resident noticed employees inspecting the realm. Yamamoto and others rallied to make their case to the harbor commissioners to save lots of the location. Whereas some port leaders have been sympathetic to the trigger, Terminal Islanders members have mentioned the group has not but obtained any particular details about the port’s intentions. The information concerning the doable demolition was first reported in Random Lengths Information — an area information journal in San Pedro.

The Port instructed The Occasions that there are at the moment no formal plans or timeline to vary the buildings, however that there have been “inner employees discussions concerning the long-term way forward for the buildings, together with the potential for demolition.”

“Any adjustments to the location would go thorough a proper and public course of, together with enter from the general public and a vote by the Los Angeles Harbor Fee. Enter from the Terminal Islanders group could be important to any course of involving change on the website,” Port of Los Angeles spokesperson Phillip Sanfield mentioned.

Harbor Fee President Lucille Roybal-Allard, L.A. Councilman Tim McOsker and port leaders plan to go to the buildings throughout the first week of September, Sanfield mentioned, earlier than the port arranges a gathering with Terminal Islanders representatives.

“Our prime precedence on this challenge [is] to assemble enter and concepts immediately from the Terminal Islanders group for the way forward for the location,” Sanfield mentioned.

As delivery forecasts have grown at one of many world’s busiest seaports, officers have allotted a whole bunch of hundreds of thousands of {dollars} for storage and rail yard enlargement, restoration and electrification initiatives, amongst others. One $18.2-million demolition challenge that’s within the design part at Terminal Island would clear the land close to the previous StarKist cannery and make it obtainable for lease. The realm is a few mile from the Tuna Road buildings.

The Terminal Islanders membership is working with the Los Angeles Conservancy and the Nationwide Belief for Historic Preservation to attempt to get a historic designation for the buildings earlier than any plans are set, Terminal Islanders board member Paul Boyea mentioned. And practically 1,000 individuals have signed a web-based and bodily petition to stop doable destruction.

“We wish to defend the legacy of the Terminal Islanders,” Boyea mentioned. “We don’t wish to simply protect [the buildings] — we wish to restore them, we wish to rehabilitate them. Perhaps there’s a special finish use for the buildings. There’s a whole lot of various things that may be accomplished.”

Boyea and others have mentioned the potential for turning the buildings right into a museum, artwork set up or, if doable, relocating them.

Right this moment, paint peels on the prime of the boarded-up buildings and stray cats wander outdoors on the desolate avenue. A “No Trespassing” signal from the Port of Los Angeles is posted to the wall and empty beer cans which have been run over by automobiles litter the bottom. Throughout the gravelly highway is an enormous lot that shops container bins. Subsequent door is a now-closed Korean mini mart, and greater than 100 yards down the road is the water’s edge. Vehicles, cranes and extra delivery containers fill the backdrop.

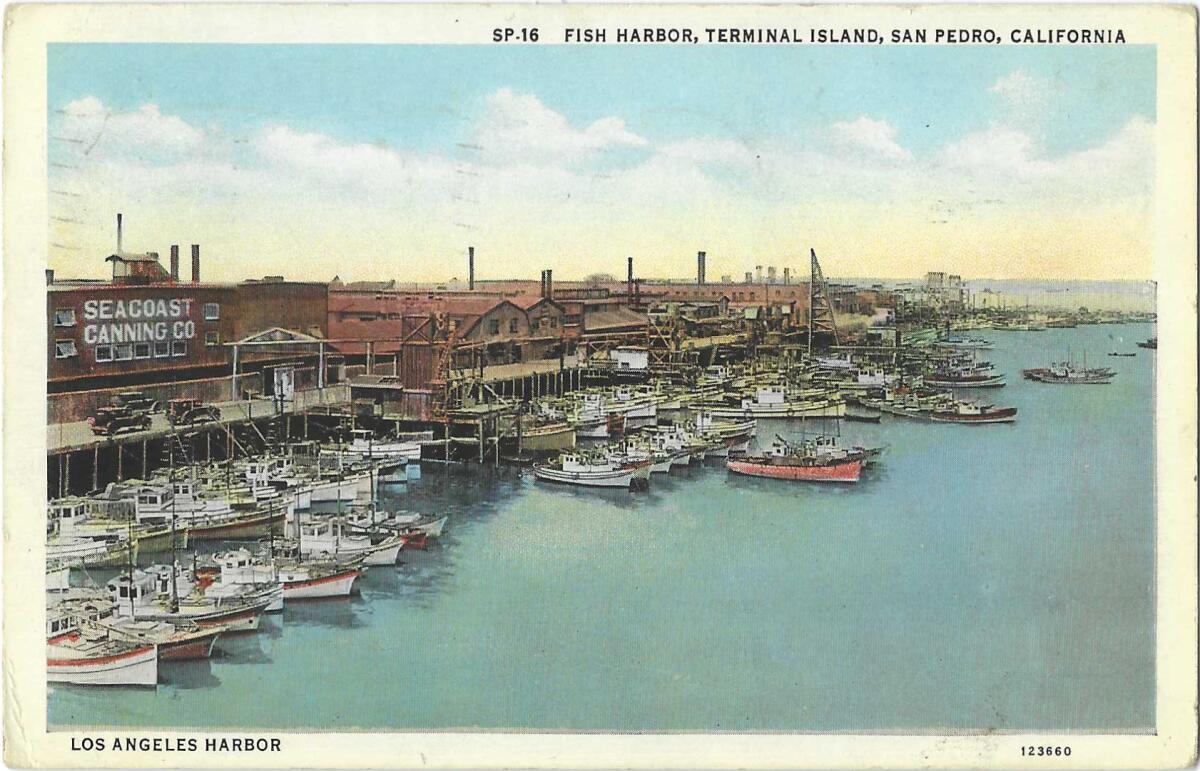

A classic postcard with a 1937 postmark, from Patt Morrison’s assortment, reveals Fish Harbor at Terminal Island. The realm was residence to Japanese fishers.

What’s left of the Terminal Island village is a stark distinction to what as soon as was a bustling village of about 3,000 individuals and the spine to the fishing business from the flip of the final century to World Warfare II. Cannery employees listened for the sound of whistles that signaled boats coming in with the day’s catch. The realm was full of storefronts and houses, a Japanese gate that graced the doorway to a Shinto shrine, a Buddhist temple, a Baptist church, a financial institution, a faculty and halls for individuals to assemble for conferences and celebrations. Tuna Road was thought of the central buying space.

In accordance with the Los Angeles Conservancy, a 1917 article in Pacific Fisherman mentioned “the Japanese taught the Individuals and all of the others the best way to catch tuna in industrial portions and they’re the very best fishermen within the sport. Consequently, the packers vie with one another in offering them with enticing quarters near their respective crops.”

Miho Shiroishi, 91, was born on the island within the Nineteen Thirties. She nonetheless drives to the realm merely to recollect life earlier than the battle. Her mom and 4 siblings have been compelled right into a camp when she was 9 whereas her father was compelled into one other. When she returned, her residence on Cannery Road not existed. However at the least the streets, she mentioned, remained.

“I’m going to be 92 this yr in November, however I’m nonetheless in a position to drive. So I’m going to Terminal Island as typically as I can,” Shiroishi mentioned. “With out [the two buildings], what do you could have? Nothing.”

The president of the Terminal Islanders Membership and one in every of Yamamoto’s pals from kindergarten, Terry Hara, mentioned that plans for the buildings’ future ought to be a collaboration of concepts “with all people’s greatest curiosity at coronary heart.”

Hara, who was the first Asian American promoted to captain on the Los Angeles Police Division in 1998 and whose mother and father lived on Terminal Island, mentioned that he and others imagine that preserving historical past is essential to educating individuals concerning the previous.

“This specific location is small within the scale of historic experiences of the Japanese Individuals, but it surely’s an necessary half and it’s the place you study concerning the tuna business. It started in Los Angeles,” Hara mentioned concerning the business that relied closely on fishing strategies introduced from Japan. “It performs an necessary position in educating these that may come after us.”

Alice Nagano, 90, was 7 when her household was compelled from Terminal Island and despatched to the Manzanar relocation middle in Inyo County. She mentioned her childhood reminiscences of her first residence are restricted, however she remembers that the tight-knit neighborhood felt secure sufficient to sleep with their doorways unlocked.

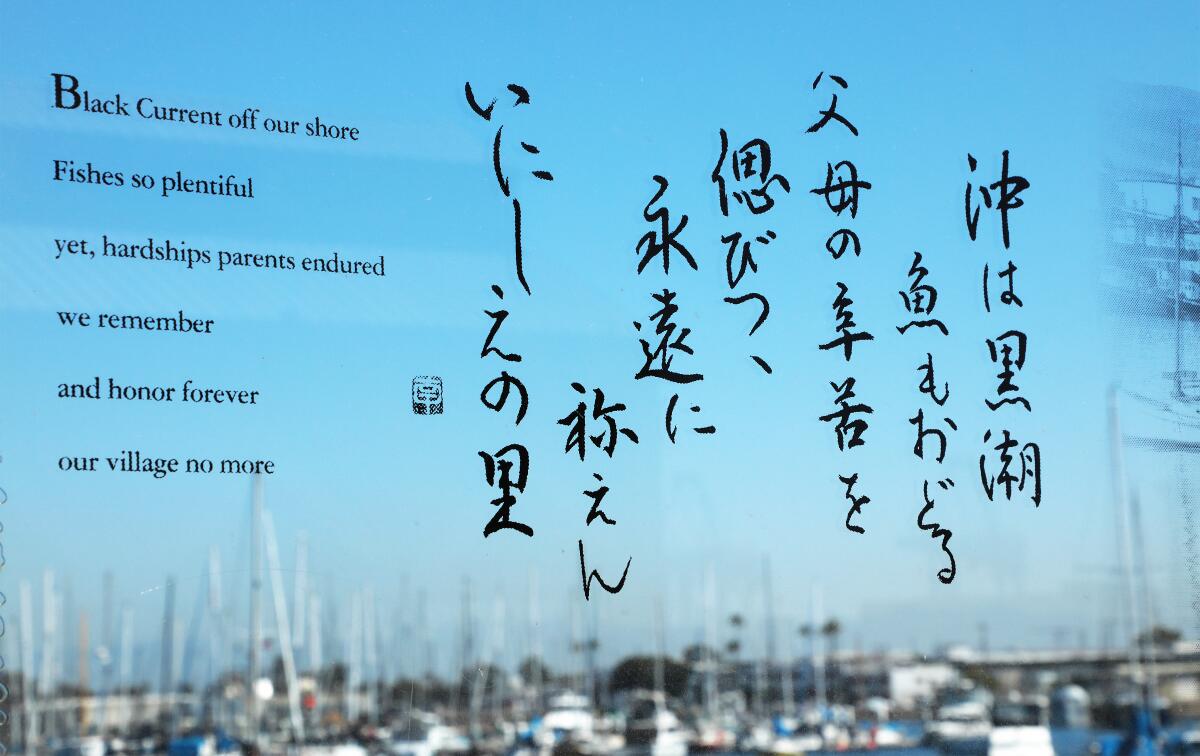

A memorial to the Japanese Fishing Village on Terminal Island serves as a reminder of the Japanese American neighborhood, its compelled evacuation in 1942, and the once-thriving fishing village at Terminal Island.

(Al Seib / For The Occasions)

“If we’ve these buildings there, at the least it’ll present that we had a neighborhood,” she mentioned. “In the event that they get demolished, there’s nothing there to remind anyone.”

There’s a memorial for Terminal Island a few mile away from Tuna Road, not removed from the federal jail. Two bronze fishermen sit atop a time capsule from 2002 and the names of Terminal Islanders are etched right into a surrounding wall. A drawing of the previous village lays throughout glass, giving individuals the possibility to think about what as soon as was. And a poem honors “our village no extra.”

A quick historical past of the city accompanies prints of black and white images — previous properties, parades, the native {hardware} store and Yamamoto’s grandfather and his previous grocery retailer.

“My mother and father are gone now and there’s actually just a bit over a handful of unique members left,” Hara mirrored. “I didn’t assume a lot of it once I was youthful, however now, I feel I’ve a little bit duty to hold on their reminiscence and historical past.”