Capital punishment in California exists in legislation, however in practicality resulted in 2019 when Gov. Gavin Newsom ordered dying row to be dismantled.

Nonetheless, 625 males and 20 ladies stay incarcerated with dying sentences, dealing with the unlikely however doable prospect that beneath a special governor, they could possibly be executed. About one-third of the condemned are Black.

In current months, Santa Clara County Dist. Atty. Jeff Rosen, as soon as a prosecutor who believed in capital punishment and one who rejects affiliation with the progressive prosecutor motion, has been quietly making ready to ask courts to alter the penalties of 14 males from his county who’re ready for that final sentence to be carried out.

Usually, he desires the court docket to re-sentence these males (Santa Clara has no ladies on dying row) to serve life with out parole. However in a couple of separate circumstances, already accomplished final 12 months, he has requested that they be given the prospect of freedom.

Santa Clara County Dist. Atty. Jeff Rosen reads at a Jewish prayer service held in February on the Congregation Kol Emeth in Palo Alto. Within the background is Elise Scher.

(Paul Kuroda / For The Occasions)

Why? An inherent racism in our justice system handed down from slavery to mass incarceration and capital punishment, he cites as a foremost motive.

“[W]e usually are not assured that these sentences have been attained with out racial bias,” his workplace wrote in a movement to courts anticipated to be filed in coming days in a number of circumstances. “We can not defend these sentences, and we imagine that implicit bias and structural racism performed some position within the dying sentence.”

For activists within the dying penalty world, that’s an previous argument. However coming from a mainstream prosecutor, it’s a mic drop.

Rosen’s unprecedented transfer (he’s the one prosecutor in California to have made such a blanket request, and the one one I might discover nationwide) has gone largely unnoticed. Nevertheless it represents a brand new battleground within the combat over the dying penalty.

Whereas many prosecutors across the state and the nation have stopped the usage of the dying penalty transferring ahead, Rosen is the primary to look again and reply the query — with collective motion — If it isn’t truthful now, how might it have been truthful then?

Subscribers get early entry to this story

We’re providing L.A. Occasions subscribers first entry to our greatest journalism. Thanks in your help.

Rosen’s transfer to undo what he sees as the continuing injustice of previous convictions places stress on different prosecutors to observe go well with, particularly these comparable to George Gascón who’ve made their status as reformers however who’ve didn’t go as far. Gascón’s workplace mentioned he has been analyzing dying penalty sentencing on a case-by-case foundation and 29 individuals have been re-sentenced out of greater than 120 on dying row convicted in L.A. However he’s unlikely to ask for a gaggle re-sentencing in an election 12 months, with a strong conservative challenger.

Santa Clara County Dist. Atty. Jeff Rosen, middle, reads from the siddur, a prayer e book, alongside Eliezer Rosengaus, left, Robert Scher and Marc Bader.

(Paul Kuroda / For The Occasions)

“It doesn’t imply that I believe issues are as unhealthy at present as they have been 50 years in the past, I utterly reject that concept,” Rosen instructed me. “However I additionally trusted that as a society, we might guarantee the elemental equity of the authorized course of for all individuals. With each exoneration, with each story of racial injustice, it turns into clear to me that this isn’t the world we reside in.”

Elisabeth Semel, director of the Loss of life Penalty Clinic at UC Berkeley, calls Rosen’s transfer “extremely vital” as a result of it examines each case in his jurisdiction, and has the potential to persuade others that it isn’t simply single circumstances that require examination, however the dying sentence as an entire — a place the Legislature’s Committee on Revision of the Penal Code advisable in 2021.

At the moment, about 35% of these on dying row are Black, regardless of Black individuals making up solely about 7% of California’s inhabitants. An extra 26% of dying row inmates are Hispanic or Mexican. General, almost 70% of dying row inmates are individuals of shade.

Semel factors out that it’s not simply the race of the alleged perpetrator that may result in the dying penalty, but in addition the race of the sufferer and the attitudes of these in command of the prosecution. Suspects accused of killing a white particular person, for instance, usually tend to face the dying penalty than these accused of killing an individual of shade.

“There’s nothing, nothing that these circumstances have extra in widespread than racial discrimination, whether or not we’re speaking about privileging white victims, that means looking for the dying penalty in white crime, or disadvantaging Black shoppers,” she mentioned.

Publication

Subscriber Unique Alert

When you’re an L.A. Occasions subscriber, you may signal as much as get alerts about early or fully unique content material.

You could often obtain promotional content material from the Los Angeles Occasions.

The inherent unfairness of the dying penalty, whether or not due to race or its finality, has been debated for years, typically with soul-searching arguments that transcend politics. Illinois Gov. George Ryan, a Republican, in 2003 issued a blanket commutation for all 167 inmates dealing with the dying penalty in his state, citing fear that “the demon of error” was ever-present — one of many first and boldest actions by a distinguished politician in opposition to the dying penalty.

Former Oregon Gov. Kate Brown, a Democrat, did the identical in 2022, re-sentencing 17 dying row prisoners to life with out parole. Twenty-three states, together with Oregon, Colorado and New Mexico, have abolished the dying penalty.

The deadly injection chamber at San Quentin State Jail in 2010.

(Related Press)

However California politicians, and voters, have been much less sure. Over time, voters have determined to maintain the dying penalty when requested by way of poll measures. Rosen has requested for it 4 instances, and received capital punishment in a single case — that of defendant Melvin Forte, convicted of sexually assaulting and murdering a younger German vacationer. Forte’s sentence is amongst these Rosen is looking for to alter.

Newsom, regardless of his moratorium, hasn’t gone so far as Brown or Ryan. That leaves the dying penalty in California largely within the palms of domestically elected prosecutors comparable to Rosen who’ve nearly no political incentive to revisit previous capital convictions.

I’m not one to simply imagine politicians, however once I requested Rosen why he was placing himself out entrance on a controversial difficulty, he instructed me it was as a result of it was the fitting factor to do. Then he instructed me how he got here to that conclusion, and it feels real as a result of I skilled one thing related myself.

Rosen’s views on the dying penalty had been shifting because the homicide of George Floyd in 2020. Shortly after, he put into place a collection of prosecutorial reforms meant to handle racial bias, together with deciding to not search the dying penalty in future circumstances.

Nevertheless it wasn’t till two journeys to Montgomery, Ala. — as soon as the capital of the Confederacy and now dwelling to the Legacy Museum, which traces the historical past of slavery by means of mass incarceration of individuals of shade — that the previous took on relevance for him as a matter of up to date justice.

How can a museum have such an influence? I went myself as a result of I couldn’t fairly think about. A contemporary monument in what can solely be described as a dismal metropolis the place the ghosts of tens of millions of trafficked people appear ever current, the museum lays out with astonishing readability a historical past that’s painful, however essential to acknowledge.

A dying row inmate is escorted again to his cell in 2016 after spending time within the yard at San Quentin.

(Gary Coronado / Los Angeles Occasions)

Twelve million Black individuals kidnapped from their houses abroad and offered at American auctions.

9 million Black People subjected to the home terror of Jim Crow-era violence that left justice within the palms of racist vigilantes. The museum paperwork the lynching of a 3-year-old woman, alongside together with her 10-year-old sister — simply two of dozens of kids killed, typically whereas legislation enforcement watched.

That violence compelled many to maneuver to the North and West to keep away from murders, rapes and beatings. However even in these supposed secure havens, together with California, 10 million Black People discovered that, identical to within the South, they have been segregated into lesser housing and lesser colleges, and in the end had lesser alternative.

Banks wouldn’t lend, police used crimes comparable to jaywalking to arrest, colleges failed to show. And past that secretive repression, they have been nonetheless not proof against the violence of the slave states — California could have lynched at the least 350 individuals between 1850 and 1935.

That segregation and bias led to 8 million Black People systemically over-incarcerated although legal guidelines and insurance policies that focused individuals of shade, and communities of shade, turning vigilante justice into authorized imprisonment.

On the Legacy Museum’s sister website, the Nationwide Memorial for Peace and Justice, the burden of that oppression and ache takes on literal significance. Rectangular metal markers, their form like a coffin hanging from a limb, function monuments to 4,400 Black People lynched between 1877 and 1950.

The markers start at eye degree, however strolling down from the hilltop website, they start to hold over guests, casting lengthy, chilly shadows.

It’s unattainable to move beneath them and never really feel their historic weight.

“I believe that if extra individuals went there, they’d assume a bit of in a different way about our nation, and hopefully act a bit of in a different way additionally,” Rosen instructed me.

Rosen speaks at a 2022 information convention.

(Stephen Lam / Related Press)

“I went there supporting the dying penalty,” he mentioned. “I left not so positive anymore.”

Although I used to be much less sure in regards to the dying penalty earlier than visiting Montgomery, I got here away, like Rosen, with no doubts that its origin is darkish and tainted.

Rosen mentioned the conclusion that was most profound for him was how typically supposedly unlawful lynchings happened with the help of legislation enforcement — too typically victims have been handed over by deputies or killed on the courthouse steps.

“If not thought-about lawful workouts of state energy, they weren’t illegal,” Rosen identified. “No person was prosecuted for them.”

It was not till properly into the twentieth century that outcry over that semi-state sanctioned homicide made it untenable even within the South. The reply to that outrage was to maneuver the killing again contained in the courthouse, with the usage of the dying penalty.

Bryan Stevenson, the founding father of the Legacy Museum and a dying penalty lawyer, calls Rosen’s determination “outstanding” as a result of it takes that true however sidelined historical past and turns it into mainstream coverage.

Bryan Stevenson stands in entrance of a set of soil gathered from racist lynching websites on the Legacy Museum, which he based.

(Christian Monterrosa / For The Occasions)

“It says one thing about our potential to confront historical past truthfully and to show the web page in a significant manner,” Stevenson instructed me. “Some individuals could not perceive it, some individuals could have points with it. However the fact is that we will create a future that enables us to start to expertise one thing that feels extra like freedom, extra like equality and extra like justice than we’ve ever skilled on this nation.”

A religious Jew, Rosen mentioned the museum and his personal experiences as a prosecutor made him query if the dying penalty can actually be separated from that basis of lynchings — and if killing as punishment can ever be simply or come from a spot of ethical authority no matter race.

“It’s not like I open the Bible and the penal code and determine what to do,” he mentioned. “I believe that in my lifetime, we are going to look again and say it was not proper to execute individuals.”

Rosen’s workplace has reached out to all of the victims within the circumstances he’s analyzing. Some are relieved to have finality within the case, he mentioned, realizing the dying penalty is de facto only a endless enchantment. Some would favor to maintain the dying sentence no matter whether or not it takes place or not.

Some have merely moved on after so a few years and are open to his argument that there needs to be limits to human justice. Rosen tells them he desires his energy, and ours, to finish at deciding the place individuals who commit the worst of the worst crimes die — in jail.

Not when.

He makes no excuses for horrific crimes that led to the dying sentences in his jurisdiction. A grandmother stabbed to dying. A spouse shot and rolled down a hill, nonetheless alive. A gasoline station attendant killed to forestall his testimony a few theft.

However he factors out that lots of the crimes that led to the dying penalty many years in the past wouldn’t have garnered the identical punishment at present. A number of the perpetrators have been convicted as youngsters, some have been equipment to the crime at a time when legal guidelines made fewer distinctions. Many have been imprisoned for greater than 30 years. Some had unfair trials.

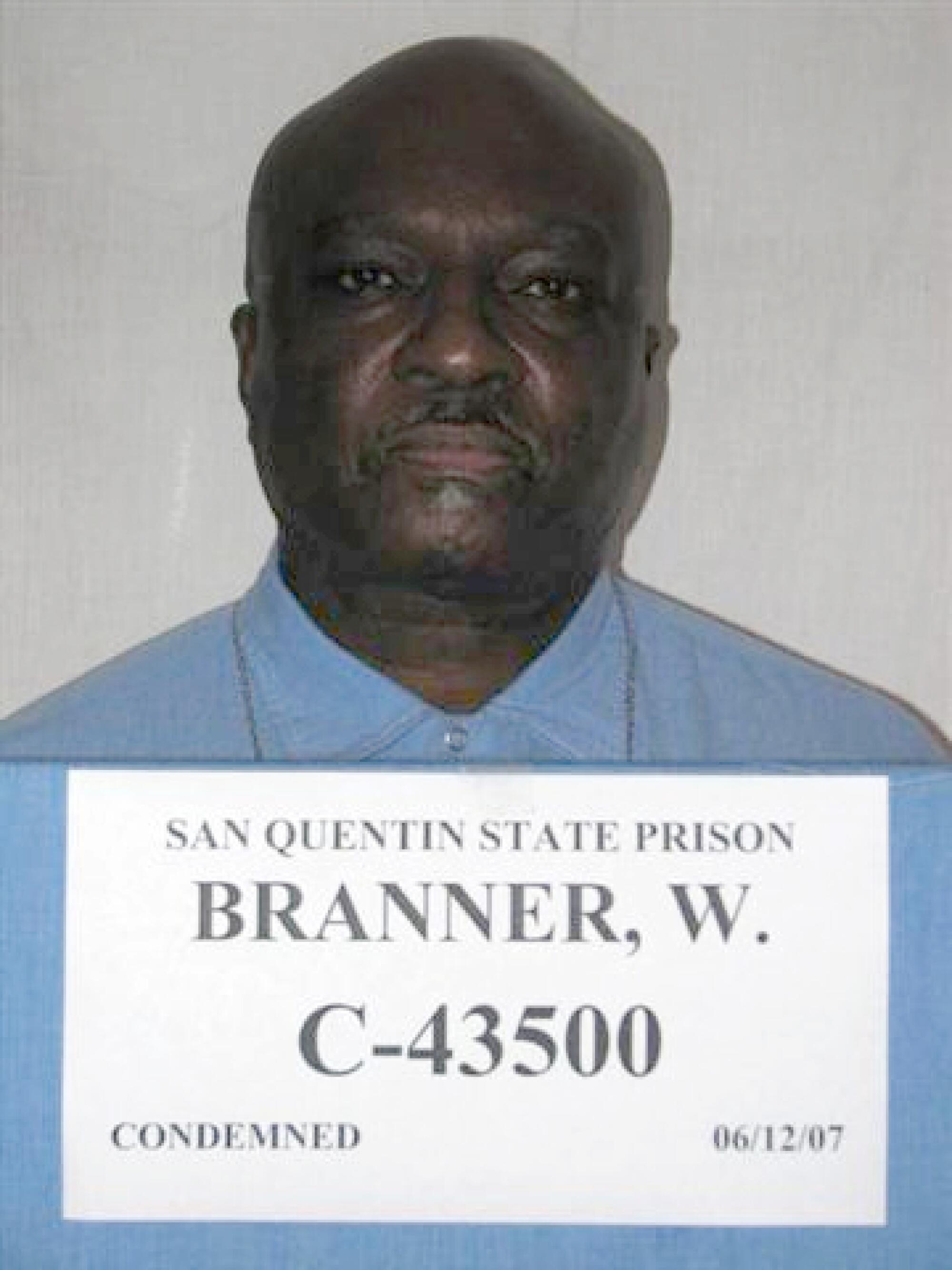

A type of males is Willie Branner, a Black man who was convicted in 1982 by an all-white jury of taking pictures and killing jewellery retailer proprietor Edward Dukor throughout a theft in Milpitas. The prosecutor in that case eliminated Black, Asian and Jewish jurors, together with eradicating one feminine Black juror partially for being “chubby and poorly groomed.”

Not too long ago, a federal court docket dominated that Branner was entitled to a brand new trial based mostly on that less-than-impartial jury.

Now 74, Branner has been, as they are saying, a mannequin prisoner. I messaged with him just lately, and he instructed me he’s relieved that his household now not has to fret about him sometime being executed. He desires of doable freedom, opening a tailoring enterprise and dealing to “assist rebuild our society for the remainder of my life, God keen.”

Branner doesn’t know the way his sentence will work out, solely that it’s going to not finish with dying. He isn’t claiming he’s harmless, simply that he has modified within the many years because the taking pictures, simply as Rosen has modified since he first started prosecuting.

“It’s not that I believe that the individuals on dying row in my county haven’t dedicated horrible, horrible crimes. They’ve,” Rosen mentioned.

There isn’t a doubt, he believes, that decency and public security demand individuals be held accountable for his or her harms.

Even when meaning holding ourselves accountable for ours.